The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (20 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

5.25Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Libertarians, anarchists, and other skeptics of the Leviathan point out that when communities are left to their own devices, they often develop norms of cooperation that allow them to settle their disputes nonviolently, without laws, police, courts, or the other trappings of government. In

Moby-Dick

, Ishmael explains how American whalers thousands of miles from the reach of the law dealt with disputes over whales that had been injured or killed by one ship and then claimed by another:

Moby-Dick

, Ishmael explains how American whalers thousands of miles from the reach of the law dealt with disputes over whales that had been injured or killed by one ship and then claimed by another:

Thus the most vexatious and violent disputes would often arise between the fishermen, were there not some written or unwritten, universal, undisputed law applicable to all cases.. . . Though no other nation [but Holland] has ever had any written whaling law, yet the American fishermen have been their own legislators and lawyers in this matter.... These laws might be engraven on a Queen Anne’s farthing, or the barb of a harpoon, and worn round the neck, so small are they.I. A Fast-Fish belongs to the party fast to it.II. A Loose-Fish is fair game for anybody who can soonest catch it.

Informal norms of this kind have emerged among fishers, farmers, and herders in many parts of the world.

46

In

Order Without Law

:

How Neighbors Settle Disputes

, the legal scholar Robert Ellickson studied a modern American version of the ancient (and frequently violent) confrontation between pastoralists and farmers. In northern California’s Shasta County, traditional ranchers are essentially cowboys, grazing their cattle in open country, while modern ranchers raise cattle in irrigated, fenced ranches. Both kinds of ranchers coexist with farmers who grow hay, alfalfa, and other crops. Straying cattle occasionally knock down fences, eat crops, foul streams, and wander onto roads where vehicles can hit them. The county is carved into “open ranges,” in which an owner is not legally liable for most kinds of accidental damage his cattle may cause, and “closed ranges,” in which he is strictly liable, whether he was negligent or not. Ellickson discovered that victims of harm by cattle were loath to invoke the legal system to settle the damages. In fact, most of the residents—ranchers, farmers, insurance adjustors, even lawyers and judges—held beliefs about the applicable laws that were flat wrong. But the residents got along by adhering to a few tacit norms. Cattle owners were always responsible for the damage their animals caused, whether a range was open or closed; but if the damage was minor and sporadic, property owners were expected to “lump it.” People kept rough long-term mental accounts of who owed what, and the debts were settled in kind rather than in cash. (For example, a cattleman whose cow damaged a rancher’s fence might at a later time board one of the rancher’s stray cattle at no charge.) Deadbeats and violators were punished with gossip and with occasional veiled threats or minor vandalism. In chapter 9 we’ll take a closer look at the moral psychology behind such norms, which fall into a category called equality matching.

47

46

In

Order Without Law

:

How Neighbors Settle Disputes

, the legal scholar Robert Ellickson studied a modern American version of the ancient (and frequently violent) confrontation between pastoralists and farmers. In northern California’s Shasta County, traditional ranchers are essentially cowboys, grazing their cattle in open country, while modern ranchers raise cattle in irrigated, fenced ranches. Both kinds of ranchers coexist with farmers who grow hay, alfalfa, and other crops. Straying cattle occasionally knock down fences, eat crops, foul streams, and wander onto roads where vehicles can hit them. The county is carved into “open ranges,” in which an owner is not legally liable for most kinds of accidental damage his cattle may cause, and “closed ranges,” in which he is strictly liable, whether he was negligent or not. Ellickson discovered that victims of harm by cattle were loath to invoke the legal system to settle the damages. In fact, most of the residents—ranchers, farmers, insurance adjustors, even lawyers and judges—held beliefs about the applicable laws that were flat wrong. But the residents got along by adhering to a few tacit norms. Cattle owners were always responsible for the damage their animals caused, whether a range was open or closed; but if the damage was minor and sporadic, property owners were expected to “lump it.” People kept rough long-term mental accounts of who owed what, and the debts were settled in kind rather than in cash. (For example, a cattleman whose cow damaged a rancher’s fence might at a later time board one of the rancher’s stray cattle at no charge.) Deadbeats and violators were punished with gossip and with occasional veiled threats or minor vandalism. In chapter 9 we’ll take a closer look at the moral psychology behind such norms, which fall into a category called equality matching.

47

As important as tacit norms are, it would be a mistake to think that they obviate a role for government. The Shasta County ranchers may not have called in Leviathan when a cow knocked over a fence, but they were living in its shadow and knew it would step in if their informal sanctions escalated or if something bigger were at stake, such as a fight, a killing, or a dispute over women. And as we shall see, their current level of peaceful coexistence is itself the legacy of a local version of the Civilizing Process. In the 1850s, the annual homicide rate of northern California ranchers was around 45 per 100,000, comparable to those of medieval Europe.

48

48

I think the theory of the Civilizing Process provides a large part of the explanation for the modern decline of violence not only because it predicted the remarkable plunge in European homicide but because it makes correct predictions about the times and places in the modern era that do not enjoy the blessed 1-per-100,000-per-year rate of modern Europe. Two of these rule-proving exceptions are zones that the Civilizing Process never fully penetrated : the lower strata of the socioeconomic scale, and the inaccessible or inhospitable territories of the globe. And two are zones in which the Civilizing Process went into reverse: the developing world, and the 1960s. Let’s visit them in turn.

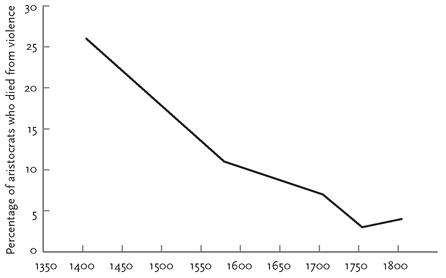

VIOLENCE AND CLASSOther than the drop in numbers, the most striking feature of the decline in European homicide is the change in the socioeconomic profile of killing. Centuries ago rich people were as violent as poor people, if not more so.

49

Gentlemen would carry swords and would not hesitate to use them to avenge insults. They often traveled with retainers who doubled as bodyguards, so an affront or a retaliation for an affront could escalate into a bloody street fight between gangs of aristocrats (as in the opening scene of

Romeo and Juliet

). The economist Gregory Clark examined records of deaths of English aristocrats from late medieval times to the Industrial Revolution. I’ve plotted his data in figure 3–7, which shows that in the 14th and 15th centuries an astonishing 26 percent of male aristocrats died from violence—about the same rate that we saw in figure 2–2 as the average for preliterate tribes. The rate fell into the single digits by the turn of the 18th century, and of course today it is essentially zero.

49

Gentlemen would carry swords and would not hesitate to use them to avenge insults. They often traveled with retainers who doubled as bodyguards, so an affront or a retaliation for an affront could escalate into a bloody street fight between gangs of aristocrats (as in the opening scene of

Romeo and Juliet

). The economist Gregory Clark examined records of deaths of English aristocrats from late medieval times to the Industrial Revolution. I’ve plotted his data in figure 3–7, which shows that in the 14th and 15th centuries an astonishing 26 percent of male aristocrats died from violence—about the same rate that we saw in figure 2–2 as the average for preliterate tribes. The rate fell into the single digits by the turn of the 18th century, and of course today it is essentially zero.

FIGURE 3–7.

Percentage of deaths of English male aristocrats from violence, 1330–1829

Percentage of deaths of English male aristocrats from violence, 1330–1829

Source:

Data from Clark, 2007a, p. 122; data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

Data from Clark, 2007a, p. 122; data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

A homicide rate measured in percentage points is still remarkably high, and well into the 18th and 19th centuries violence was a part of the lives of respectable men, such as Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Boswell quotes Samuel Johnson, who presumably had no trouble defending himself with words, as saying, “I have beat many a fellow, but the rest had the wit to hold their tongues.”

50

Members of the upper classes eventually refrained from using force against one another, but with the law watching their backs, they reserved the right to use it against their inferiors. As recently as 1859 the British author of

The Habits of a Good Society

advised:

50

Members of the upper classes eventually refrained from using force against one another, but with the law watching their backs, they reserved the right to use it against their inferiors. As recently as 1859 the British author of

The Habits of a Good Society

advised:

There are men whom nothing but a physical punishment will bring to reason, and with these we shall have to deal at some time of our lives. A lady is insulted or annoyed by an unwieldy bargee, or an importunate and dishonest cabman. One well-dealt blow settles the whole matter.... A man therefore, whether he aspires to be a gentleman or not, should learn to box.... There are but few rules for it, and those are suggested by common sense. Strike out, strike straight, strike suddenly; keep one arm to guard, and punish with the other. Two gentlemen never fight; the art of boxing is brought into use in punishing a stronger and more imprudent man of a class beneath your own.

51

The European decline of violence was spearheaded by a decline in

elite

violence. Today statistics from every Western country show that the overwhelming majority of homicides and other violent crimes are committed by people in the lowest socioeconomic classes. One obvious reason for the shift is that in medieval times, one

achieved

high status through the use of force. The journalist Steven Sailer recounts an exchange from early-20th-century England: “A hereditary member of the British House of Lords complained that Prime Minister Lloyd George had created new Lords solely because they were self-made millionaires who had only recently acquired large acreages. When asked, ‘How did your ancestor become a Lord?’ he replied sternly, ‘With the battle-ax, sir, with the battle-ax!’ ”

52

elite

violence. Today statistics from every Western country show that the overwhelming majority of homicides and other violent crimes are committed by people in the lowest socioeconomic classes. One obvious reason for the shift is that in medieval times, one

achieved

high status through the use of force. The journalist Steven Sailer recounts an exchange from early-20th-century England: “A hereditary member of the British House of Lords complained that Prime Minister Lloyd George had created new Lords solely because they were self-made millionaires who had only recently acquired large acreages. When asked, ‘How did your ancestor become a Lord?’ he replied sternly, ‘With the battle-ax, sir, with the battle-ax!’ ”

52

As the upper classes were putting down their battle-axes, disarming their retinues, and no longer punching out bargees and cabmen, the middle classes followed suit. They were domesticated not by the royal court, of course, but by other civilizing forces. Employment in factories and businesses forced employees to acquire habits of decorum. An increasingly democratic political process allowed them to identify with the institutions of government and society, and it opened up the court system as a way to pursue their grievances. And then came an institution that was introduced in London in 1828 by Sir Robert Peel and soon named after him, the municipal police, or bobbies.

53

53

The main reason that violence correlates with low socioeconomic status today is that the elites and the middle class pursue justice with the legal system while the lower classes resort to what scholars of violence call “self-help.” This has nothing to do with

Women Who Love Too Much

or

Chicken Soup for the Soul;

it is another name for vigilantism, frontier justice, taking the law into your own hands, and other forms of violent retaliation by which people secured justice in the absence of intervention by the state.

Women Who Love Too Much

or

Chicken Soup for the Soul;

it is another name for vigilantism, frontier justice, taking the law into your own hands, and other forms of violent retaliation by which people secured justice in the absence of intervention by the state.

In an influential article called “Crime as Social Control,” the legal scholar Donald Black argued that most of what we call crime is, from the point of view of the perpetrator, the pursuit of justice.

54

Black began with a statistic that has long been known to criminologists: only a minority of homicides (perhaps as few as 10 percent) are committed as a means to a practical end, such as killing a homeowner during a burglary, a policeman during an arrest, or the victim of a robbery or rape because dead people tell no tales.

55

The most common motives for homicide are moralistic: retaliation after an insult, escalation of a domestic quarrel, punishing an unfaithful or deserting romantic partner, and other acts of jealousy, revenge, and self-defense. Black cites some cases from a database in Houston:

54

Black began with a statistic that has long been known to criminologists: only a minority of homicides (perhaps as few as 10 percent) are committed as a means to a practical end, such as killing a homeowner during a burglary, a policeman during an arrest, or the victim of a robbery or rape because dead people tell no tales.

55

The most common motives for homicide are moralistic: retaliation after an insult, escalation of a domestic quarrel, punishing an unfaithful or deserting romantic partner, and other acts of jealousy, revenge, and self-defense. Black cites some cases from a database in Houston:

One in which a young man killed his brother during a heated discussion about the latter’s sexual advances toward his younger sisters, another in which a man killed his wife after she “dared” him to do so during an argument about which of several bills they should pay, one where a woman killed her husband during a quarrel in which the man struck her daughter (his stepdaughter), one in which a woman killed her 21-year-old son because he had been “fooling around with homosexuals and drugs,” and two others in which people died from wounds inflicted during altercations over the parking of an automobile.

Most homicides, Black notes, are really instances of capital punishment, with a private citizen as the judge, jury, and executioner. It’s a reminder that the way we conceive of a violent act depends on which of the corners of the violence triangle (see figure 2–1) we stake out as our vantage point. Consider a man who is arrested and tried for wounding his wife’s lover. From the point of view of the law, the aggressor is the husband and the victim is society, which is now pursuing justice (an interpretation, recall, captured in the naming of court cases, such as

The People vs. John Doe

). From the point of view of the lover, the aggressor is the husband, and he is the victim; if the husband gets off on an acquittal or mistrial or plea bargain, there is no justice, as the lover is enjoined from pursuing revenge. And from the point of view of the husband,

he

is the victim (of cuckoldry), the lover is the aggressor, and justice has been done—but now he is the victim of a second act of aggression, in which the state is the aggressor and the lover is an accomplice. Black notes:

The People vs. John Doe

). From the point of view of the lover, the aggressor is the husband, and he is the victim; if the husband gets off on an acquittal or mistrial or plea bargain, there is no justice, as the lover is enjoined from pursuing revenge. And from the point of view of the husband,

he

is the victim (of cuckoldry), the lover is the aggressor, and justice has been done—but now he is the victim of a second act of aggression, in which the state is the aggressor and the lover is an accomplice. Black notes:

Those who commit murder . . . often appear to be resigned to their fate at the hands of the authorities; many wait patiently for the police to arrive; some even call to report their own crimes.... In cases of this kind, indeed, the individuals involved might arguably be regarded as martyrs. Not unlike workers who violate a prohibition to strike—knowing they will go to jail—or others who defy the law on grounds of principle, they do what they think is right, and willingly suffer the consequences.

56

These observations overturn many dogmas about violence. One is that violence is caused by a deficit of morality and justice. On the contrary, violence is often caused by a surfeit of morality and justice, at least as they are conceived in the minds of the perpetrators. Another dogma, cherished among psychologists and public health researchers, is that violence is a kind of disease.

57

But this public health theory of violence flouts the basic definition of a disease, namely a malfunction that causes suffering to the individual.

58

Most violent people insist there is nothing wrong with them; it’s the victim and bystanders who think there’s a problem. A third dubious belief about violence is that lower-class people engage in it because they are financially needy (for example, stealing food to feed their children) or because they are expressing rage against society. The violence of a lower-class man may indeed express rage, but it is aimed not at society but at the asshole who scraped his car and dissed him in front of a crowd.

57

But this public health theory of violence flouts the basic definition of a disease, namely a malfunction that causes suffering to the individual.

58

Most violent people insist there is nothing wrong with them; it’s the victim and bystanders who think there’s a problem. A third dubious belief about violence is that lower-class people engage in it because they are financially needy (for example, stealing food to feed their children) or because they are expressing rage against society. The violence of a lower-class man may indeed express rage, but it is aimed not at society but at the asshole who scraped his car and dissed him in front of a crowd.

Other books

Good Woman Blues by Emery, Lynn

The Odds Get Even by Natale Ghent

Royal Secrets by Abramson, Traci Hunter

A Hot Mess (The Truth in Lies Saga #3) by Jeanne McDonald

Death in a Serene City by Edward Sklepowich

Discipline of the Private House by Esme Ombreux

Dangerous Dream by Kami Garcia, Margaret Stohl

Odio by David Moody

The Magic Wagon by Joe R. Lansdale

Peggy Dulle - Liza Wilcox 04 - Saddle Up by Peggy Dulle