The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (23 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

8.37Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

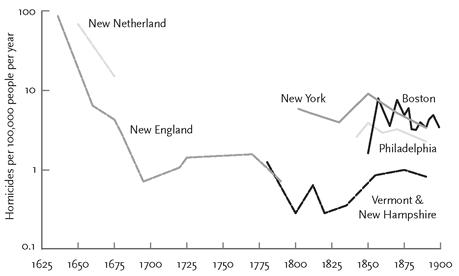

FIGURE 3–13.

Homicide rates in the northeastern United States, 1636–1900

Homicide rates in the northeastern United States, 1636–1900

Sources:

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. New England: pp. 38, 62. New Netherland: pp. 38, 50. New York: p. 185. New Hampshire and Vermont: p. 184. Philadelphia: p. 185. Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. Estimates for “unrelated adults” have been multiplied by 1.1 to make them approximately commensurable with estimates for all adults.

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. New England: pp. 38, 62. New Netherland: pp. 38, 50. New York: p. 185. New Hampshire and Vermont: p. 184. Philadelphia: p. 185. Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. Estimates for “unrelated adults” have been multiplied by 1.1 to make them approximately commensurable with estimates for all adults.

The zigzags for the northeastern cities show two twists in the American version of the Civilizing Process. The middling altitude of these lines along the homicide scale, down from the ceiling but hovering well above the floor, suggests that the consolidation of a frontier under government control can bring the annual homicide rate down by an order of magnitude or so, from around 100 per 100,000 to around 10. But unlike what happened in Europe, where the momentum continued all the way down to the neighborhood of 1, in America the rate usually got stuck in the 5-to-15 range, where we find it today. Roth suggests that once an effective government has pacified the populace from the 100 to the 10 range, additional reductions depend on the degree to which people accept the legitimacy of the government, its laws, and the social order. Eisner, recall, made a similar observation about the Civilizing Process in Europe.

The other twist on the American version of the Civilizing Process is that in many of Roth’s mini-datasets, violence

increased

in the middle decades of the 19th century.

80

The buildup and aftermath of the Civil War disrupted the social balance in many parts of the country, and the northeastern cities saw a wave of immigration from Ireland, which (as we have seen) lagged behind England in its homicide decline. Irish Americans in the 19th century, like African Americans in the 20th, were more pugnacious than their neighbors, in large part because they and the police did not take each other seriously.

81

But in the second half of the 19th century police forces in American cities expanded, became more professional, and began to serve the criminal justice system rather than administering their own justice on the streets with their nightsticks. In major northern cities well into the 20th century, homicide rates for white Americans declined.

82

increased

in the middle decades of the 19th century.

80

The buildup and aftermath of the Civil War disrupted the social balance in many parts of the country, and the northeastern cities saw a wave of immigration from Ireland, which (as we have seen) lagged behind England in its homicide decline. Irish Americans in the 19th century, like African Americans in the 20th, were more pugnacious than their neighbors, in large part because they and the police did not take each other seriously.

81

But in the second half of the 19th century police forces in American cities expanded, became more professional, and began to serve the criminal justice system rather than administering their own justice on the streets with their nightsticks. In major northern cities well into the 20th century, homicide rates for white Americans declined.

82

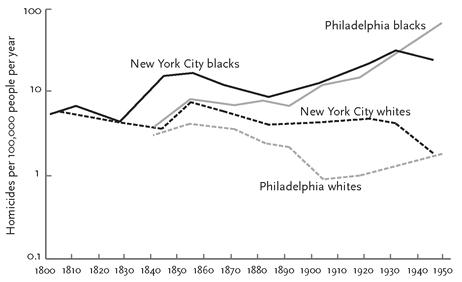

FIGURE 3–14.

Homicide rates among blacks and whites in New York and Philadelphia, 1797–1952

Homicide rates among blacks and whites in New York and Philadelphia, 1797–1952

Sources:

New York 1797–1845: Roth, 2009, p. 195. New York 1856–85: Average of Roth, 2009, p. 195, and Gurr, 1989a, p. 39. New York 1905–53: Gurr, 1989a, p. 39. Philadelphia: 1842–94: Roth, 2009, p. 195. Philadelphia 1907–28: Lane, 1989, p. 72 (15-year averages). Philadelphia, 1950s: Gurr, 1989a, pp. 38–39. Roth’s estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. His estimates for Philadelphia were, in addition, multiplied by 1.1 and 1.5 to compensate, respectively, for unrelated versus all victims and indictments versus homicides (Roth, 2009, p. 492). Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

New York 1797–1845: Roth, 2009, p. 195. New York 1856–85: Average of Roth, 2009, p. 195, and Gurr, 1989a, p. 39. New York 1905–53: Gurr, 1989a, p. 39. Philadelphia: 1842–94: Roth, 2009, p. 195. Philadelphia 1907–28: Lane, 1989, p. 72 (15-year averages). Philadelphia, 1950s: Gurr, 1989a, pp. 38–39. Roth’s estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. His estimates for Philadelphia were, in addition, multiplied by 1.1 and 1.5 to compensate, respectively, for unrelated versus all victims and indictments versus homicides (Roth, 2009, p. 492). Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

But the second half of the 19th century also saw a fateful change. The graphs I have shown so far plot the rates for American whites. Figure 3–14 shows the rates for two cities in which black-on-black and white-on-white homicides can be distinguished. The graph reveals that the racial disparity in American homicide has not always been with us. In the northeastern cities, in New England, in the Midwest, and in Virginia, blacks and whites killed at similar rates throughout the first half of the 19th century. Then a gap opened up, and it widened even further in the 20th century, when homicides among African Americans skyrocketed, going from three times the white rate in New York in the 1850s to almost thirteen times the white rate a century later.

83

A probe into the causes, including economic and residential segregation, could fill another book. But one of them, as we have seen, is that communities of lower-income African Americans were effectively stateless, relying on a culture of honor (sometimes called “the code of the streets”) to defend their interests rather calling in the law.

84

83

A probe into the causes, including economic and residential segregation, could fill another book. But one of them, as we have seen, is that communities of lower-income African Americans were effectively stateless, relying on a culture of honor (sometimes called “the code of the streets”) to defend their interests rather calling in the law.

84

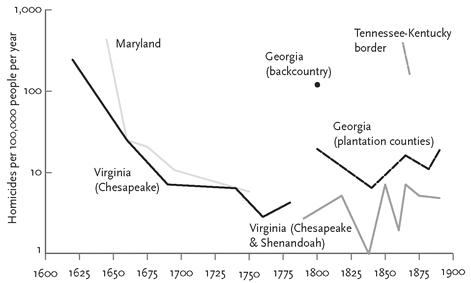

The first successful English settlements in America were in New England and Virginia, and a comparison of figure 3–13 and figure 3–15 might make you think that in their first century the two colonies underwent similar civilizing processes. Until, that is, you read the numbers on the vertical axis. They show that the graph for the Northeast runs from 0.1 to 100, while the graph for the Southeast runs from 1 to 1,000, ten times higher. Unlike the black-white gap, the North-South gap has deep roots in American history. The Chesapeake colonies of Maryland and Virginia started out more violent than New England, and though they descended into the moderate range (between 1 and 10 homicides per 100,000 people per year) and stayed there for most of the 19th century, other parts of the settled South bounced around in the low 10-to-100 range, such as the Georgia plantation counties shown on the graph. Many remote and mountainous regions, such as the Georgia backcountry and Tennessee-Kentucky border, continued to float in the uncivilized 100s, some of them well into the 19th century.

Why has the South had such a long history of violence? The most sweeping answer is that the civilizing mission of government never penetrated the American South as deeply as it had the Northeast, to say nothing of Europe. The historian Pieter Spierenburg has provocatively suggested that “democracy came too early” to America.

85

In Europe, first the state disarmed the people and claimed a monopoly on violence, then the people took over the apparatus of the state. In America, the people took over the state before it had forced them to lay down their arms—which, as the Second Amendment famously affirms, they reserve the right to keep and bear. In other words Americans, and especially Americans in the South and West, never fully signed on to a social contract that would vest the government with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. In much of American history, legitimate force was also wielded by posses, vigilantes, lynch mobs, company police, detective agencies, and Pinkertons, and even more often kept as a prerogative of the individual.

85

In Europe, first the state disarmed the people and claimed a monopoly on violence, then the people took over the apparatus of the state. In America, the people took over the state before it had forced them to lay down their arms—which, as the Second Amendment famously affirms, they reserve the right to keep and bear. In other words Americans, and especially Americans in the South and West, never fully signed on to a social contract that would vest the government with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. In much of American history, legitimate force was also wielded by posses, vigilantes, lynch mobs, company police, detective agencies, and Pinkertons, and even more often kept as a prerogative of the individual.

FIGURE 3–15.

Homicide rates in the southeastern United States, 1620–1900

Homicide rates in the southeastern United States, 1620–1900

Sources:

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. Virginia (Chesapeake): pp. 39, 84. Virginia (Chesapeake and Shenandoah): p. 201. Georgia: p. 162. Tennessee-Kentucky: pp. 336–37. Zero value for Virginia, 1838, plotted as 1 since the log of 0 is undefined. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495.

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. Virginia (Chesapeake): pp. 39, 84. Virginia (Chesapeake and Shenandoah): p. 201. Georgia: p. 162. Tennessee-Kentucky: pp. 336–37. Zero value for Virginia, 1838, plotted as 1 since the log of 0 is undefined. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495.

This power sharing, historians have noted, has always been sacred in the South. As Eric Monkkonen puts it, in the 19th century “the South had a deliberately weak state, eschewing things such as penitentiaries in favor of local, personal violence.”

86

Homicides were treated lightly if the killing was deemed “reasonable,” and “most killings . . . in the rural South were reasonable, in the sense that the victim had not done everything possible to escape from the killer, that the killing resulted from a personal dispute, or because the killer and victim were the kinds of people who kill each other.”

87

86

Homicides were treated lightly if the killing was deemed “reasonable,” and “most killings . . . in the rural South were reasonable, in the sense that the victim had not done everything possible to escape from the killer, that the killing resulted from a personal dispute, or because the killer and victim were the kinds of people who kill each other.”

87

The South’s reliance on self-help justice has long been a part of its mythology. It was instilled early in life, such as in the maternal advice given to the young Andrew Jackson (the dueling president who claimed to rattle with bullets when he walked): “Never . . . sue anyone for slander or assault or battery; always settle those cases yourself.”

88

It was flaunted by pugnacious icons of the mountainous South like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, the “King of the Wild Frontier.” It fueled the war between the prototypical feuding families, the Hatfields and McCoys of the Kentucky–West Virginia backcountry. And it not only swelled the homicide statistics for as long as they have been recorded, but has left its mark on the southern psyche today.

89

88

It was flaunted by pugnacious icons of the mountainous South like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, the “King of the Wild Frontier.” It fueled the war between the prototypical feuding families, the Hatfields and McCoys of the Kentucky–West Virginia backcountry. And it not only swelled the homicide statistics for as long as they have been recorded, but has left its mark on the southern psyche today.

89

Self-help justice depends on the credibility of one’s prowess and resolve, and to this day the American South is marked by an obsession with credible deterrence, otherwise known as a culture of honor. The essence of a culture of honor is that it does not sanction predatory or instrumental violence, but only retaliation after an insult or other mistreatment. The psychologists Richard Nisbett and Dov Cohen have shown that this mindset continues to pervade southern laws, politics, and attitudes.

90

Southerners do not outkill northerners in homicides carried out during robberies, they found, only in those sparked by quarrels. In surveys, southerners do not endorse the use of violence in the abstract, but only to protect home and family. The laws of the southern states sanction this morality. They give a person wide latitude to kill in defense of self or property, put fewer restrictions on gun purchases, allow corporal punishment (“paddling”) in schools, and specify the death penalty for murder, which their judicial systems are happy to carry out. Southern men and women are more likely to serve in the military, to study at military academies, and to take hawkish positions on foreign policy.

90

Southerners do not outkill northerners in homicides carried out during robberies, they found, only in those sparked by quarrels. In surveys, southerners do not endorse the use of violence in the abstract, but only to protect home and family. The laws of the southern states sanction this morality. They give a person wide latitude to kill in defense of self or property, put fewer restrictions on gun purchases, allow corporal punishment (“paddling”) in schools, and specify the death penalty for murder, which their judicial systems are happy to carry out. Southern men and women are more likely to serve in the military, to study at military academies, and to take hawkish positions on foreign policy.

In a series of ingenious experiments, Nisbett and Cohen also showed that honor looms large in the behavior of individual southerners. In one study, they sent fake letters inquiring about jobs to companies all over the country. Half of them contained the following confession:

There is one thing I must explain, because I feel I must be honest and I want no misunderstandings. I have been convicted of a felony, namely manslaughter. You will probably want an explanation for this before you send me an application, so I will provide it. I got into a fight with someone who was having an affair with my fiancée. I lived in a small town, and one night this person confronted me in front of my friends at the bar. He told everyone that he and my fiancée were sleeping together. He laughed at me to my face and asked me to step outside if I was man enough. I was young and didn’t want to back down from a challenge in front of everyone. As we went into the alley, he started to attack me. He knocked me down, and he picked up a bottle. I could have run away and the judge said I should have, but my pride wouldn’t let me. Instead I picked up a pipe that was laying in the alley and hit him with it. I didn’t mean to kill him, but he died a few hours later at the hospital. I realize that what I did was wrong.

The other half contained a similar paragraph in which the applicant confessed to a felony conviction for grand theft auto, which, he said, he had foolishly committed to help support his wife and young children. In response to the letter confessing to the honor killing, companies based in the South and West were more likely than those in the North to send the letter-writer a job application, and their replies were warmer in tone. For example, the owner of one southern store apologized that she had no jobs available at the time and added:

As for your problem of the past, anyone could probably be in the situation you were in. It was just an unfortunate incident that shouldn’t be held against you. Your honesty shows that you are sincere.... I wish you the best of luck for your future. You have a positive attitude and a willingness to work. Those are the qualities that businesses look for in an employee. Once you get settled, if you are near here, please stop in and see us.

91

Other books

Rosemary for the Holidays (Consulting Magic) by Amy Crook

AWOL on the Appalachian Trail by Miller, David

Merging Assets by Cheryl Dragon

A Kiss to Seal the Deal by Nikki Logan

Agatha Christie by The House of Lurking Death: A Tommy, Tuppence SS

White-Hot Christmas by Serenity Woods

Marius' Mules V: Hades' Gate by Turney, S.J.A.

Shhh... Gianna's Side by M. Robinson

The Abandoned Puppy by Holly Webb

Weddings Bells Times Four by Trinity Blacio