The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (24 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

6.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

No such warmth came from companies based in the North, nor from any company when the letter confessed to auto theft. Indeed, northern companies were more forgiving of the auto theft than the honor killing; the southern and western companies were more forgiving of the honor killing than the auto theft.

Nisbett and Cohen also captured the southern culture of honor in the lab. Their subjects were not bubbas from the bayous but affluent students at the University of Michigan who had lived in the South for at least six years. Students were recruited for a psychology experiment on “limited response time conditions on certain facets of human judgment” (a bit of gobbledygook to hide the real purpose of the study). In the hallway on their way to the lab, the students had to pass by an accomplice of the experimenter who was filing papers in a cabinet. In half of the cases, when the student brushed past the accomplice, he slammed the drawer shut and muttered, “Asshole.” Then the experimenter (who was kept in the dark as to whether the student had been insulted) welcomed the student into the lab, observed his demeanor, gave him a questionnaire, and drew a blood sample. The students from the northern states, they found, laughed off the insult and behaved no differently from the control group who had entered without incident. But the insulted students from the southern states walked in fuming. They reported lower self-esteem in a questionnaire, and their blood samples showed elevated levels of testosterone and of cortisol, a stress hormone. They behaved more dominantly toward the experimenter and shook his hand more firmly, and when approaching another accomplice in the narrow hallway on their way out, they refused to step aside to let him pass.

92

92

Is there an exogenous cause that might explain why the South rather than the North developed a culture of honor? Certainly the brutality needed to maintain a slave economy might have been a factor, but the most violent parts of the South were backcountry regions that never depended on plantation slavery (see figure 3–15). Nisbett and Cohen were influenced by David Hackett Fisher’s

Albion’s Seed

, a history of the British colonization of the United States, and zeroed in on the origins of the first colonists from different parts of Europe. The northern states were settled by Puritan, Quaker, Dutch, and German farmers, but the interior South was largely settled by Scots-Irish, many of them sheepherders, who hailed from the mountainous periphery of the British Isles beyond the reach of the central government. Herding, Nisbett and Cohen suggest, may have been an exogenous cause of the culture of honor. Not only does a herder’s wealth lie in stealable physical assets, but those assets have feet and can be led away in an eyeblink, far more easily than land can be stolen out from under a farmer. Herders all over the world cultivate a hair trigger for violent retaliation. Nisbett and Cohen suggest that the Scots-Irish brought their culture of honor with them and kept it alive when they took up herding in the South’s mountainous frontier. Though contemporary southerners are no longer shepherds, cultural mores can persist long after the ecological circumstances that gave rise to them are gone, and to this day southerners behave as if they have to be tough enough to deter livestock rustlers.

Albion’s Seed

, a history of the British colonization of the United States, and zeroed in on the origins of the first colonists from different parts of Europe. The northern states were settled by Puritan, Quaker, Dutch, and German farmers, but the interior South was largely settled by Scots-Irish, many of them sheepherders, who hailed from the mountainous periphery of the British Isles beyond the reach of the central government. Herding, Nisbett and Cohen suggest, may have been an exogenous cause of the culture of honor. Not only does a herder’s wealth lie in stealable physical assets, but those assets have feet and can be led away in an eyeblink, far more easily than land can be stolen out from under a farmer. Herders all over the world cultivate a hair trigger for violent retaliation. Nisbett and Cohen suggest that the Scots-Irish brought their culture of honor with them and kept it alive when they took up herding in the South’s mountainous frontier. Though contemporary southerners are no longer shepherds, cultural mores can persist long after the ecological circumstances that gave rise to them are gone, and to this day southerners behave as if they have to be tough enough to deter livestock rustlers.

The herding hypothesis requires that people cling to an occupational strategy for centuries after it has become dysfunctional, but the more general theory of a culture of honor does not depend on that assumption. People often take up herding in mountainous areas because it’s hard to grow crops on mountains, and mountainous areas are often anarchic because they are the hardest regions for a state to conquer, pacify, and administer. The immediate trigger for self-help justice, then, is anarchy, not herding itself. Recall that the ranchers of Shasta County have herded cattle for more than a century, yet when one of them suffers a minor loss of cattle or property, he is expected to “lump it,” not lash out with violence to defend his honor. Also, a recent study that compared southern counties in their rates of violence and their suitability for herding found no correlation when other variables were controlled.

93

93

So it’s sufficient to assume that settlers from the remote parts of Britain ended up in the remote parts of the South, and that both regions were lawless for a long time, fostering a culture of honor. We still have to explain why their culture of honor is so self-sustaining. After all, a functioning criminal justice system has been in place in southern states for some time now. Perhaps honor has staying power because the first man who dares to abjure it would be heaped with contempt for cowardice and treated as an easy mark.

The American West, even more than the American South, was a zone of anarchy until well into the 20th century. The cliché of Hollywood westerns that “the nearest sheriff is ninety miles away” was the reality in millions of square miles of territory, and the result was the other cliché of Hollywood westerns, ever-present violence. Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, drinking in American popular culture during his cross-country escape with Lolita, savors the “ox-stunning fisticuffs” of the cowboy movies:

There was the mahogany landscape, the florid-faced, blue-eyed roughriders, the prim pretty schoolteacher arriving in Roaring Gulch, the rearing horse, the spectacular stampede, the pistol thrust through the shivered windowpane, the stupendous fist fight, the crashing mountain of dusty old-fashioned furniture, the table used as a weapon, the timely somersault, the pinned hand still groping for the dropped bowie knife, the grunt, the sweet crash of fist against chin, the kick in the belly, the flying tackle; and immediately after a plethora of pain that would have hospitalized a Hercules, nothing to show but the rather becoming bruise on the bronzed cheek of the warmed-up hero embracing his gorgeous frontier bride.

94

In

Violent Land

, the historian David Courtwright shows that the Hollywood horse operas were accurate in the levels of violence they depicted, if not in their romanticized image of cowboys. The life of a cowboy alternated between dangerous, backbreaking work and payday binges of drinking, gambling, whoring, and brawling. “For the cowboy to become a symbol of the American experience required an act of moral surgery. The cowboy as mounted protector and risk-taker was remembered. The cowboy as dismounted drunk sleeping it off on the manure pile behind the saloon was forgotten.”

95

Violent Land

, the historian David Courtwright shows that the Hollywood horse operas were accurate in the levels of violence they depicted, if not in their romanticized image of cowboys. The life of a cowboy alternated between dangerous, backbreaking work and payday binges of drinking, gambling, whoring, and brawling. “For the cowboy to become a symbol of the American experience required an act of moral surgery. The cowboy as mounted protector and risk-taker was remembered. The cowboy as dismounted drunk sleeping it off on the manure pile behind the saloon was forgotten.”

95

In the American Wild West, annual homicide rates were fifty to several hundred times higher than those of eastern cities and midwestern farming regions: 50 per 100,000 in Abilene, Kansas, 100 in Dodge City, 229 in Fort Griffin, Texas, and 1,500 in Wichita.

96

The causes were right out of Hobbes. The criminal justice system was underfunded, inept, and often corrupt. “In 1877,” notes Courtwright, “some five thousand men were on the wanted list in Texas alone, not a very encouraging sign of efficiency in law enforcement.”

97

Self-help justice was the only way to deter horse thieves, cattle rustlers, highwaymen, and other brigands. The guarantor of its deterrent threat was a reputation for resolve that had to be defended at all costs, epitomized by the epitaph on a Colorado grave marker: “He Called Bill Smith a Liar.”

98

One eyewitness described the casus belli of a fight that broke out during a card game in the caboose of a cattle train. One man remarked, “I don’t like to play cards with a dirty deck.” A cowboy from a rival company thought he said “dirty neck,” and when the gunsmoke cleared, one man was dead and three wounded.

99

96

The causes were right out of Hobbes. The criminal justice system was underfunded, inept, and often corrupt. “In 1877,” notes Courtwright, “some five thousand men were on the wanted list in Texas alone, not a very encouraging sign of efficiency in law enforcement.”

97

Self-help justice was the only way to deter horse thieves, cattle rustlers, highwaymen, and other brigands. The guarantor of its deterrent threat was a reputation for resolve that had to be defended at all costs, epitomized by the epitaph on a Colorado grave marker: “He Called Bill Smith a Liar.”

98

One eyewitness described the casus belli of a fight that broke out during a card game in the caboose of a cattle train. One man remarked, “I don’t like to play cards with a dirty deck.” A cowboy from a rival company thought he said “dirty neck,” and when the gunsmoke cleared, one man was dead and three wounded.

99

It wasn’t just cowboy country that developed in Hobbesian anarchy; so did parts of the West settled by miners, railroad workers, loggers, and itinerant laborers. Here is an assertion of property rights found attached to a post during the California Gold Rush of 1849:

All and everybody, this is my claim, fifty feet on the gulch, cordin to Clear Creek District Law, backed up by shotgun amendments.... Any person found trespassing on this claim will be persecuted to the full extent of the law. This is no monkey tale butt I will assert my rites at the pint of the sicks shirter if leagally necessary so taik head and good warning.

100

Courtwright cites an average annual homicide rate at the time of 83 per 100,000 and points to “an abundance of other evidence that Gold Rush California was a brutal and unforgiving place. Camp Names were mimetic: Gouge Eye, Murderers Bar, Cut-Throat Gulch, Graveyard Flat. There was a Hangtown, a Helltown, a Whiskeytown, and a Gomorrah, though, interestingly, no Sodom.”

101

Mining boom towns elsewhere in the West also had annual homicide rates in the upper gallery: 87 per 100,000 in Aurora, Nevada; 105 in Leadville, Colorado; 116 in Bodie, California; and a whopping 24,000 (almost one in four) in Benton, Wyoming.

101

Mining boom towns elsewhere in the West also had annual homicide rates in the upper gallery: 87 per 100,000 in Aurora, Nevada; 105 in Leadville, Colorado; 116 in Bodie, California; and a whopping 24,000 (almost one in four) in Benton, Wyoming.

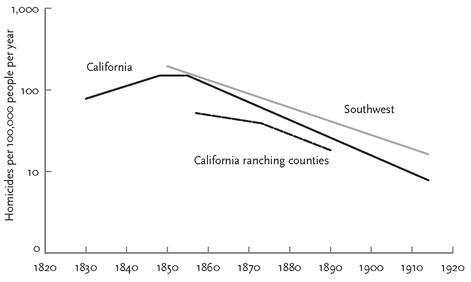

In figure 3–16 I’ve plotted the trajectory of western violence, using snapshots of annual homicide rates that Roth provides for a given region at two or more times. The curve for California shows a rise around the 1849 Gold Rush, but then, together with that of the southwestern states, it shows the signature of the Civilizing Process: a greater-than-tenfold decline in homicide rates, from the range of 100 to 200 per 100,000 people to the range of 5 to 15 (though, as in the South, the rates did not continue to fall into the 1s and 2s of Europe and New England). I’ve included the decline for the California ranching counties, like those studied by Ellickson, to show how their current norm-governed coexistence came only after a long period of lawless violence.

FIGURE 3–16.

Homicide rates in the southwestern United States and California, 1830–1914

Homicide rates in the southwestern United States and California, 1830–1914

Sources:

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. California (estimates): pp. 183, 360, 404. California ranching counties: p. 355. Southwest, 1850 (estimate): p. 354. Southwest, 1914 (Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico): p. 404. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495.

Data from Roth, 2009, whites only. California (estimates): pp. 183, 360, 404. California ranching counties: p. 355. Southwest, 1850 (estimate): p. 354. Southwest, 1914 (Arizona, Nevada, and New Mexico): p. 404. Estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495.

So at least five of the major regions of the United States—the Northeast, the middle Atlantic states, the coastal South, California, and the Southwest—underwent civilizing processes, but at different times and to different extents. The decline of violence in the American West lagged that in the East by two centuries and spanned the famous 1890 announcement of the closing of the American frontier, which symbolically marked the end of anarchy in the United States.

Anarchy was not the only cause of the mayhem in the Wild West and other violent zones in expanding America such as laborers’ camps, hobo villages, and Chinatowns (as in, “Forget it, Jake; it’s Chinatown”). Courtwright shows that the wildness was exacerbated by a combination of demography and evolutionary psychology. These regions were peopled by young, single men who had fled impoverished farms and urban ghettos to seek their fortune in the harsh frontier. The one great universal in the study of violence is that most of it is committed by fifteen-to-thirty-year-old men.

102

Not only are males the more competitive sex in most mammalian species, but with

Homo sapiens

a man’s position in the pecking order is secured by reputation, an investment with a lifelong payout that must be started early in adulthood.

102

Not only are males the more competitive sex in most mammalian species, but with

Homo sapiens

a man’s position in the pecking order is secured by reputation, an investment with a lifelong payout that must be started early in adulthood.

The violence of men, though, is modulated by a slider: they can allocate their energy along a continuum from competing with other men for access to women to wooing the women themselves and investing in their children, a continuum that biologists sometimes call “cads versus dads.”

103

In a social ecosystem populated mainly by men, the optimal allocation for an individual man is at the “cad” end, because attaining alpha status is necessary to beat away the competition and a prerequisite to getting within wooing distance of the scarce women. Also favoring cads is a milieu in which women are more plentiful but some of the men can monopolize them. In these settings it can pay to gamble with one’s life because, as Daly and Wilson have noted, “any creature that is recognizably on track toward complete reproductive failure must somehow expend effort, often at risk of death, to try to improve its present life trajectory.”

104

The ecosystem that selects for the “dad” setting is one with an equal number of men and women and monogamous matchups between them. In those circumstances, violent competition offers the men no reproductive advantages, but it does threaten them with a big disadvantage: a man cannot support his children if he is dead.

103

In a social ecosystem populated mainly by men, the optimal allocation for an individual man is at the “cad” end, because attaining alpha status is necessary to beat away the competition and a prerequisite to getting within wooing distance of the scarce women. Also favoring cads is a milieu in which women are more plentiful but some of the men can monopolize them. In these settings it can pay to gamble with one’s life because, as Daly and Wilson have noted, “any creature that is recognizably on track toward complete reproductive failure must somehow expend effort, often at risk of death, to try to improve its present life trajectory.”

104

The ecosystem that selects for the “dad” setting is one with an equal number of men and women and monogamous matchups between them. In those circumstances, violent competition offers the men no reproductive advantages, but it does threaten them with a big disadvantage: a man cannot support his children if he is dead.

Other books

The Fourth Stall Part III by Chris Rylander

The Singles by Emily Snow

Storm the Author's Cut by Vanessa Grant

Talking Dirty With the Boss: A Talking Dirty Novel (Entangled Indulgence) by Ashenden, Jackie

Prince Charming by Foley, Gaelen

Single Combat by Dean Ing

Betrayal (Book 2: Time Enough to Love) by Jaxon, Jenna

Powered by Cheyanne Young

The Resurrectionist by James Bradley

Tying You Down by Cheyenne McCray