The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (22 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

13.11Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Most important, the Enga took well to the Pax Australiana beginning in the late 1930s. Over the span of two decades warfare plummeted, and many of the Enga were relieved to set aside violence to settle their disputes and “fight in courts” instead of on the battlefield.

When Papua New Guinea gained independence in 1975, violence among the Enga shot back up. Government officials doled out land and perks to their clansmen, provoking intimidation and revenge from the clans left in the cold. Young men left the bachelor cults for schools that prepared them for nonexistent jobs, then joined “Raskol” criminal gangs that were unrestrained by elders and the norms they had imposed. They were attracted by alcohol, drugs, nightclubs, gambling, and firearms (including M-16s and AK-47s) and went on rampages of rape, plunder, and arson, not unlike the knights of medieval Europe. The state was weak: its police were untrained and outgunned, and its corrupt bureaucracy was incapable of maintaining order. In short, the governance vacuum left by instant decolonization put the Papuans through a decivilizing process that left them with neither traditional norms nor modern third-party enforcement. Similar degenerations have occurred in other former colonies in the developing world, forming eddies in the global flow toward lower rates of homicide.

It’s easy for a Westerner to think that violence in lawless parts of the world is intractable and permanent. But at various times in history communities have gotten so fed up with the bloodshed that they have launched what criminologists call a civilizing offensive.

72

Unlike the unplanned reductions in homicide that came about as a by-product of the consolidation of states and the promotion of commerce, a civilizing offensive is a deliberate effort by sectors of a community (often women, elders, or clergy) to tame the Rambos and Raskols and restore civilized life. Wiessner reports on a civilizing offensive in the Enga province in the 2000s.

73

Church leaders tried to lure young men from the thrill of gang life with exuberant sports, music, and prayer, and to substitute an ethic of forgiveness for the ethic of revenge. Tribal elders, using the cell phones that had been introduced in 2007, developed rapid response units to apprise one another of disputes and rush to the trouble spot before the fighting got out of control. They reined in the most uncontrollable firebrands in their own clans, sometimes with brutal public executions. Community governments were set up to restrict gambling, drinking, and prostitution. And a newer generation was receptive to these efforts, having seen that “the lives of Rambos are short and lead nowhere.” Wiessner quantified the results: after having increased for decades, the number of killings declined significantly from the first half of the 2000s to the second. As we shall see, it was not the only time and place in which a civilizing offensive has paid off.

VIOLENCE IN THESE UNITED STATES72

Unlike the unplanned reductions in homicide that came about as a by-product of the consolidation of states and the promotion of commerce, a civilizing offensive is a deliberate effort by sectors of a community (often women, elders, or clergy) to tame the Rambos and Raskols and restore civilized life. Wiessner reports on a civilizing offensive in the Enga province in the 2000s.

73

Church leaders tried to lure young men from the thrill of gang life with exuberant sports, music, and prayer, and to substitute an ethic of forgiveness for the ethic of revenge. Tribal elders, using the cell phones that had been introduced in 2007, developed rapid response units to apprise one another of disputes and rush to the trouble spot before the fighting got out of control. They reined in the most uncontrollable firebrands in their own clans, sometimes with brutal public executions. Community governments were set up to restrict gambling, drinking, and prostitution. And a newer generation was receptive to these efforts, having seen that “the lives of Rambos are short and lead nowhere.” Wiessner quantified the results: after having increased for decades, the number of killings declined significantly from the first half of the 2000s to the second. As we shall see, it was not the only time and place in which a civilizing offensive has paid off.

Violence is as American as cherry pie.

—H. Rap Brown

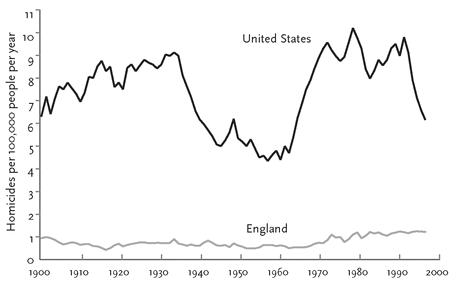

The Black Panther spokesman may have mixed up his fruits, but he did express a statistically valid generalization about the United States. Among Western democracies, the United States leaps out of the homicide statistics. Instead of clustering with kindred peoples like Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, it hangs out with toughs like Albania and Uruguay, close to the median rate for the entire world. Not only has the homicide rate for the United States not wafted down to the levels enjoyed by every European and Commonwealth democracy, but it showed no overall decline during the 20th century, as we see in figure 3–10. (For the 20th-century graphs, I will use a linear rather than a logarithmic scale.)

FIGURE 3–10.

Homicide rates in the United States and England, 1900–2000

Homicide rates in the United States and England, 1900–2000

Sources:

Graph from Monkkonen, 2001, pp. 171, 185–88; see also Zahn & McCall, 1999, p. 12. Note that Monkkonen’s U.S. data differ slightly from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports data plotted in figure 3–18 and cited in this chapter.

Graph from Monkkonen, 2001, pp. 171, 185–88; see also Zahn & McCall, 1999, p. 12. Note that Monkkonen’s U.S. data differ slightly from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports data plotted in figure 3–18 and cited in this chapter.

The American homicide rate crept up until 1933, nose-dived in the 1930s and 1940s, remained low in the 1950s, and then was launched skyward in 1962, bouncing around in the stratosphere in the 1970s and 1980s before returning to earth starting in 1992. The upsurge in the 1960s was shared with every other Western democracy, and I’ll return to it in the next section. But why did the United States start the century with homicide rates so much higher than England’s, and never close the gap? Could it be a counterexample to the generalization that countries with good governments and good economies enjoy a civilizing process that pushes their rate of violence downward? And if so, what is unusual about the United States? In newspaper commentaries one often reads pseudo-explanations like this: “Why is America more violent? It’s our cultural predisposition to violence.”

74

How can we find our way out of this logical circle? It’s not just that America is gun-happy. Even if you subtract all the killings with firearms and count only the ones with rope, knives, lead pipes, wrenches, candlesticks, and so on, Americans commit murders at a higher rate than Europeans.

75

74

How can we find our way out of this logical circle? It’s not just that America is gun-happy. Even if you subtract all the killings with firearms and count only the ones with rope, knives, lead pipes, wrenches, candlesticks, and so on, Americans commit murders at a higher rate than Europeans.

75

Europeans have always thought America is uncivilized, but that is only partly true. A key to understanding American homicide is to remember that

the United States

was originally a plural noun, as in

these United States

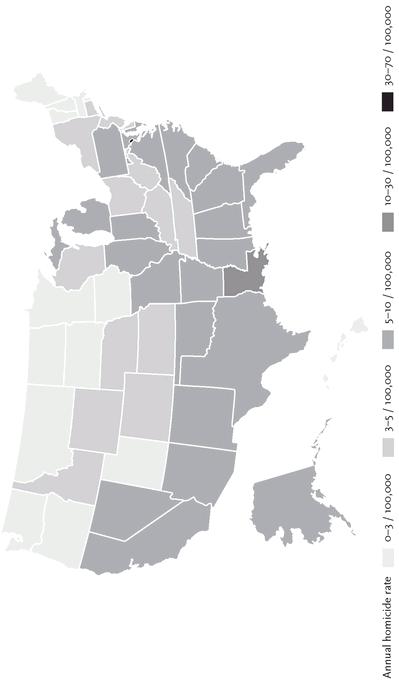

. When it comes to violence, the United States is not a country; it’s three countries. Figure 3–11 is a map that plots the 2007 homicide rates for the fifty states, using the same shading scheme as the world map in figure 3–9.

the United States

was originally a plural noun, as in

these United States

. When it comes to violence, the United States is not a country; it’s three countries. Figure 3–11 is a map that plots the 2007 homicide rates for the fifty states, using the same shading scheme as the world map in figure 3–9.

FIGURE 3-11. Geography of homicide in the United States, 2007

Source:

Data from U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2007, table4. Crime in the United States by Region, Geographical Division, and State, 2006-7

Data from U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2007, table4. Crime in the United States by Region, Geographical Division, and State, 2006-7

The shading shows that

some

of the United States are not so different from Europe after all. They include the aptly named New England states, and a band of northern states stretching toward the Pacific (Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas, Montana, and the Pacific Northwest states), together with Utah. The band reflects not a common climate, since Oregon’s is nothing like Vermont’s, but rather the historical routes of migration, which tended to go from east to west. This ribbon of peaceable states, with homicide rates of less than 3 per 100,000 per year, sits at the top of a gradient of increasing homicide from north to south. At the southern end we find states like Arizona (7.4) and Alabama (8.9), which compare unfavorably to Uruguay (5.3), Jordan (6.9), and Grenada (4.9). We also find Louisiana (14.2), whose rate is close to that of Papua New Guinea (15.2).

76

some

of the United States are not so different from Europe after all. They include the aptly named New England states, and a band of northern states stretching toward the Pacific (Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas, Montana, and the Pacific Northwest states), together with Utah. The band reflects not a common climate, since Oregon’s is nothing like Vermont’s, but rather the historical routes of migration, which tended to go from east to west. This ribbon of peaceable states, with homicide rates of less than 3 per 100,000 per year, sits at the top of a gradient of increasing homicide from north to south. At the southern end we find states like Arizona (7.4) and Alabama (8.9), which compare unfavorably to Uruguay (5.3), Jordan (6.9), and Grenada (4.9). We also find Louisiana (14.2), whose rate is close to that of Papua New Guinea (15.2).

76

A second contrast is less visible on the map. Louisiana’s homicide rate is higher than those of the other southern states, and the District of Columbia (a barely visible black speck) is off the scale at 30.8, in the range of the most dangerous Central American and southern African countries. These jurisdictions are outliers mainly because they have a high proportion of African Americans. The current black-white difference in homicide rates within the United States is stark. Between 1976 and 2005 the average homicide rate for white Americans was 4.8, while the average rate for black Americans was 36.9.

77

It’s not just that blacks get arrested and convicted more often, which would suggest that the race gap might be an artifact of racial profiling. The same gap appears in anonymous surveys in which victims identify the race of their attackers, and in surveys in which people of both races recount their own history of violent offenses.

78

By the way, though the southern states have a higher percentage of African Americans than the northern states, the North-South difference is not a by-product of the white-black difference. Southern whites are more violent than northern whites, and southern blacks are more violent than northern blacks.

79

77

It’s not just that blacks get arrested and convicted more often, which would suggest that the race gap might be an artifact of racial profiling. The same gap appears in anonymous surveys in which victims identify the race of their attackers, and in surveys in which people of both races recount their own history of violent offenses.

78

By the way, though the southern states have a higher percentage of African Americans than the northern states, the North-South difference is not a by-product of the white-black difference. Southern whites are more violent than northern whites, and southern blacks are more violent than northern blacks.

79

So while northern Americans and white Americans are somewhat more violent than Western Europeans (whose median homicide rate is 1.4), the gap between them is far smaller than it is for the country as a whole. And a little digging shows that the United States did undergo a state-driven civilizing process, though different regions underwent it at different times and to different degrees. Digging is necessary because for a long time the United States was a backwards country when it came to keeping track of homicide. Most homicides are prosecuted by individual states, not by the federal government, and good nationwide statistics weren’t compiled until the 1930s. Also, until recently “the United States” was a moving target. The lower forty-eight were not fully assembled until 1912, and many states were periodically infused with a shot of immigrants who changed the demographic profile until they coalesced in the melting pot. For these reasons, historians of American violence have had to make do with shorter time series from smaller jurisdictions. In

American Homicide

Randolph Roth has recently assembled an enormous number of small-scale datasets for the three centuries of American history before the national statistics were compiled. Though most of the trends are roller coasters rather than toboggan runs, they do show how different parts of the country became civilized as the anarchy of the frontier gave way—in part—to state control.

American Homicide

Randolph Roth has recently assembled an enormous number of small-scale datasets for the three centuries of American history before the national statistics were compiled. Though most of the trends are roller coasters rather than toboggan runs, they do show how different parts of the country became civilized as the anarchy of the frontier gave way—in part—to state control.

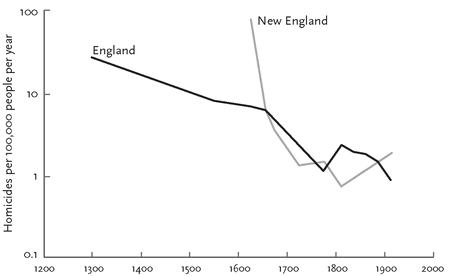

FIGURE 3–12.

Homicide rates in England, 1300–1925, and New England, 1630–1914

Homicide rates in England, 1300–1925, and New England, 1630–1914

Sources:

Data for England: Eisner, 2003. Data for New England: 1630–37, Roth, 2001, p. 55; 1650–1800: Roth, 2001, p. 56; 1914: Roth, 2009, p. 388. Roth’s estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

Data for England: Eisner, 2003. Data for New England: 1630–37, Roth, 2001, p. 55; 1650–1800: Roth, 2001, p. 56; 1914: Roth, 2009, p. 388. Roth’s estimates have been multiplied by 0.65 to convert the rate from per-adults to per-people; see Roth, 2009, p. 495. Data representing a range of years are plotted at the midpoint of the range.

Figure 3–12 superimposes Roth’s data from New England on Eisner’s compilation of homicide rates from England. The sky-high point for colonial New England represents Roth’s Elias-friendly observation that “the era of frontier violence, during which the homicide rate stood at over 100 per 100,000 adults per year, ended in 1637 when English colonists and their Native American allies established their hegemony over New England.” After this consolidation of state control, the curves for old England and New England coincide uncannily.

The rest of the Northeast also saw a plunge from triple-digit and high-double-digit homicide rates to the single digits typical of the world’s countries today. The Dutch colony of New Netherland, with settlements from Connecticut to Delaware, saw a sharp decline in its early decades, from 68 to 15 per 100,000 (figure 3–13). But when the data resume in the 19th century, we start to see the United States diverging from the two mother countries. Though the more rural and ethnically homogeneous parts of New England (Vermont and New Hampshire) continue to hover in the peaceful basement beneath 1 in 100,000, the city of Boston became more violent in the middle of the 19th century, overlapping cities in former New Netherland such as New York and Philadelphia.

Other books

Dark Tomorrow (Bo Blackman Book 6) by Helen Harper

Dirty Little Secret: New Adult Rock Star Romance (Not Exactly A Stepbrother Romance Book 1) by Kristen Strassel, Allyson Starr

Bad Move by Linwood Barclay

Neighbourhood Watch by Lisette Ashton

Cosmic Hotel by Russ Franklin

Monkey Mayhem by Bindi Irwin

The Atlantis Legacy - A01-A02 by Greanias, Thomas

A Cup of Water Under My Bed by Daisy Hernandez

The Last Camellia: A Novel by Sarah Jio