The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (17 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

4Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

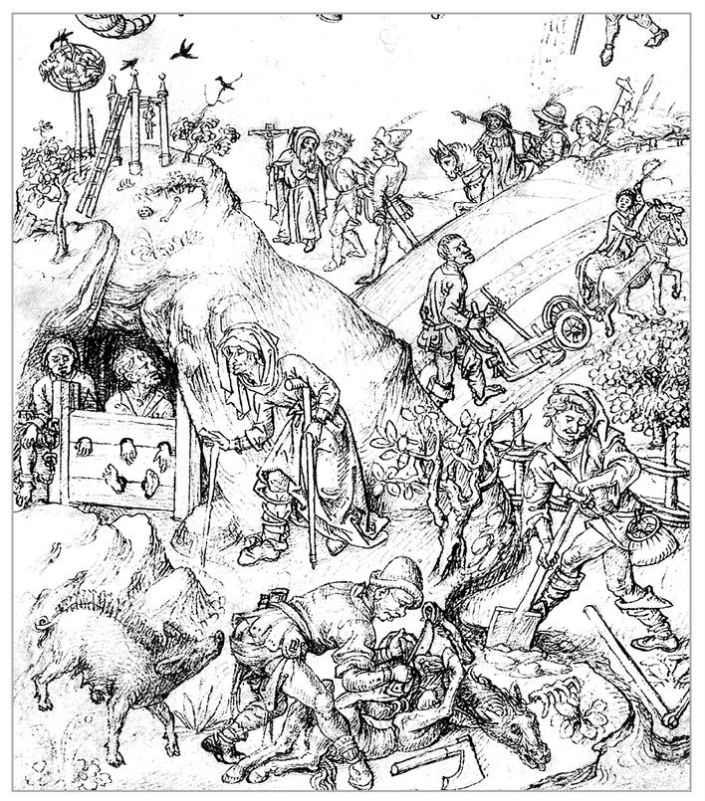

FIGURE 3–5.

Detail from “Saturn,”

Das Mittelalterliche Hausbuch

(

The Medieval Housebook,

1475–80)

Detail from “Saturn,”

Das Mittelalterliche Hausbuch

(

The Medieval Housebook,

1475–80)

Sources:

Reproduced in Elias, 1939/2000, appendix 2; see Graf zu Waldburg Wolfegg, 1988.

Reproduced in Elias, 1939/2000, appendix 2; see Graf zu Waldburg Wolfegg, 1988.

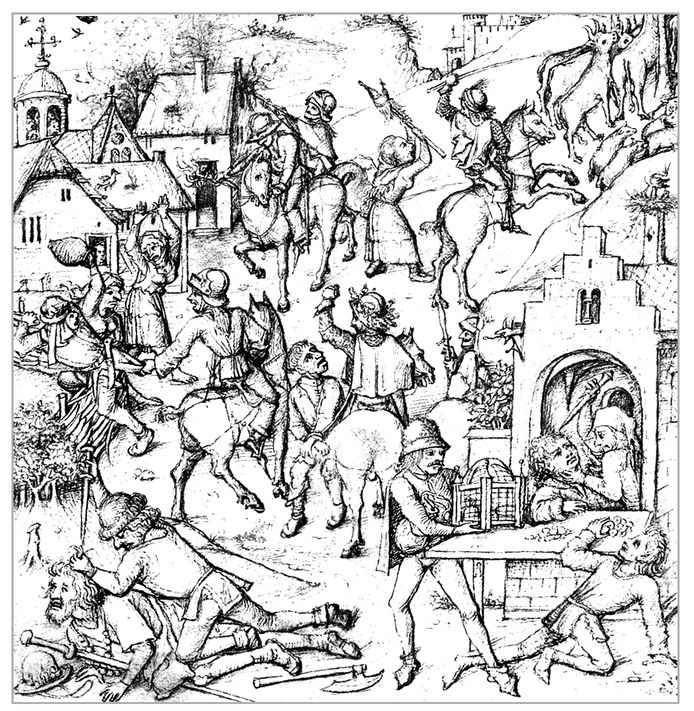

Figure 3–6 contains a detail from a second drawing, in which knights are attacking a village. In the lower left a peasant is stabbed by a soldier; above him, another peasant is restrained by his shirttail while a woman, hands in the air, cries out. At the lower right, a peasant is being stabbed in a chapel while his possessions are plundered, and nearby another peasant in fetters is cudgeled by a knight. Above them a group of horsemen are setting fire to a farmhouse, while one of them drives off the farmer’s cattle and strikes at his wife.

The knights of feudal Europe were what today we would call warlords.

FIGURE 3–6.

Detail from “Mars,”

Das Mittelalterliche Hausbuch

(

The Medieval Housebook,

1475–80)

Detail from “Mars,”

Das Mittelalterliche Hausbuch

(

The Medieval Housebook,

1475–80)

Sources:

Reproduced in Elias, 1939/2000, appendix 2; see Graf zu Waldburg Wolfegg, 1988.

Reproduced in Elias, 1939/2000, appendix 2; see Graf zu Waldburg Wolfegg, 1988.

States were ineffectual, and the king was merely the most prominent of the noblemen, with no permanent army and little control over the country. Governance was outsourced to the barons, knights, and other noblemen who controlled fiefs of various sizes, exacting crops and military service from the peasants who lived in them. The knights raided one another’s territories in a Hobbesian dynamic of conquest, preemptive attack, and vengeance, and as the

Housebook

illustrations suggest, they did not restrict their killing to other knights. In

A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century

, the historian Barbara Tuchman describes the way they made a living:

Housebook

illustrations suggest, they did not restrict their killing to other knights. In

A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century

, the historian Barbara Tuchman describes the way they made a living:

These private wars were fought by the knights with furious gusto and a single strategy, which consisted in trying to ruin the enemy by killing and maiming as many of his peasants and destroying as many crops, vineyards, tools, barns, and other possessions as possible, thereby reducing his sources of revenue. As a result, the chief victim of the belligerents was their respective peasantry.

13

As we saw in chapter 1, to maintain the credibility of their deterrent threat, knights engaged in bloody tournaments and other demonstrations of macho prowess, gussied up with words like

honor, valor, chivalry, glory,

and

gallantry

, which made later generations forget they were bloodthirsty marauders.

honor, valor, chivalry, glory,

and

gallantry

, which made later generations forget they were bloodthirsty marauders.

The private wars and tournaments were the backdrop to a life that was violent in other ways. As we saw, religious values were imparted with bloody crucifixes, threats of eternal torture, and prurient depictions of mutilated saints. Craftsmen applied their ingenuity to sadistic machines of punishment and execution. Brigands made travel a threat to life and limb, and ransoming captives was big business. As Elias noted, “the little people, too—the hatters, the tailors, the shepherds—were all quick to draw their knives.”

14

Even clergymen got into the act. The historian Barbara Hanawalt quotes an account from 14th-century England:

14

Even clergymen got into the act. The historian Barbara Hanawalt quotes an account from 14th-century England:

It happened at Ylvertoft on Saturday next before Martinmass in the fifth year of King Edward that a certain William of Wellington, parish chaplain of Ylvertoft, sent John, his clerk, to John Cobbler’s house to buy a candle for him for a penny. But John would not send it to him without the money wherefore William became enraged, and, knocking in the door upon him, he struck John in the front part of the head so that his brains flowed forth and he died forthwith.

15

Violence pervaded their entertainment as well. Tuchman describes two of the popular sports of the time: “Players with hands tied behind them competed to kill a cat nailed to a post by battering it to death with their heads, at the risk of cheeks ripped open or eyes scratched out by the frantic animal’s claws.... Or a pig enclosed in a wide pen was chased by men with clubs to the laughter of spectators as he ran squealing from the blows until beaten lifeless.”

16

16

During my decades in academia I have read thousands of scholarly papers on a vast range of topics, from the grammar of irregular verbs to the physics of multiple universes. But the oddest journal article I have ever read is “Losing Face, Saving Face: Noses and Honour in the Late Medieval Town.”

17

Here the historian Valentin Groebner documents dozens of accounts from medieval Europe in which one person cut off the nose of another. Sometimes it was an official punishment for heresy, treason, prostitution, or sodomy, but more often it was an act of private vengeance. In one case in Nuremberg in 1520, Hanns Rigel had an affair with the wife of Hanns von Eyb. A jealous von Eyb cut off the nose of Rigel’s innocent wife, a supreme injustice multiplied by the fact that Rigel was sentenced to four weeks of imprisonment for adultery while von Eyb walked away scot-free. These mutilations were so common that, according to Groebner,

17

Here the historian Valentin Groebner documents dozens of accounts from medieval Europe in which one person cut off the nose of another. Sometimes it was an official punishment for heresy, treason, prostitution, or sodomy, but more often it was an act of private vengeance. In one case in Nuremberg in 1520, Hanns Rigel had an affair with the wife of Hanns von Eyb. A jealous von Eyb cut off the nose of Rigel’s innocent wife, a supreme injustice multiplied by the fact that Rigel was sentenced to four weeks of imprisonment for adultery while von Eyb walked away scot-free. These mutilations were so common that, according to Groebner,

the authors of late-medieval surgical textbooks also devote particular attention to nasal injuries, discussing whether a nose once cut off can grow back, a controversial question that the French royal physician Henri de Mondeville answered in his famous

Chirurgia

with a categorical “No.” Other fifteenth-century medical authorities were more optimistic: Heinrich von Pforspundt’s 1460 pharmacoepia promised, among other things, a prescription for “making a new nose” for those who had lost theirs.

18

The practice was the source of our strange idiom

to cut off your nose to spite your face.

In late medieval times, cutting off someone’s nose was the prototypical act of spite.

to cut off your nose to spite your face.

In late medieval times, cutting off someone’s nose was the prototypical act of spite.

Like other scholars who have peered into medieval life, Elias was taken aback by accounts of the temperament of medieval people, who by our lights seem impetuous, uninhibited, almost childlike:

Not that people were always going around with fierce looks, drawn brows and martial countenances.... On the contrary, a moment ago they were joking, now they mock each other, one word leads to another, and suddenly from the midst of laughter they find themselves in the fiercest feud. Much of what appears contradictory to us—the intensity of their piety, the violence of their fear of hell, their guilt feelings, their penitence, the immense outbursts of joy and gaiety, the sudden flaring and the uncontrollable force of their hatred and belligerence—all these, like the rapid changes of mood, are in reality symptoms of one and the same structuring of the emotional life. The drives, the emotions were vented more freely, more directly, more openly than later. It is only to us, in whom everything is more subdued, moderate, and calculated, and in whom social taboos are built much more deeply into the fabric of our drive-economy as self-restraints, that the unveiled intensity of this piety, belligerence, or cruelty appears to be contradictory.

19

Tuchman too writes of the “childishness noticeable in medieval behavior, with its marked inability to restrain any kind of impulse.”

20

Dorothy Sayers, in the introduction to her translation of

The Song of Roland

, adds, “The idea that a strong man should react to great personal and national calamities by a slight compression of the lips and by silently throwing his cigarette into the fireplace is of very recent origin.”

21

20

Dorothy Sayers, in the introduction to her translation of

The Song of Roland

, adds, “The idea that a strong man should react to great personal and national calamities by a slight compression of the lips and by silently throwing his cigarette into the fireplace is of very recent origin.”

21

Though the childishness of the medievals was surely exaggerated, there may indeed be differences in degree in the mores of emotional expression in different eras. Elias spends much of

The Civilizing Process

documenting this transition with an unusual database: manuals of etiquette. Today we think of these books, like

Amy Vanderbilt’s Everyday Etiquette

and

Miss Manners’ Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior

, as sources of handy tips for avoiding embarrassing peccadilloes. But at one time they were serious guides to moral conduct, written by the leading thinkers of the day. In 1530 the great scholar Desiderius Erasmus, one of the founders of modernity, wrote an etiquette manual called

On Civility in Boys

which was a bestseller throughout Europe for two centuries. By laying down rules for what people ought not to do, these manuals give us a snapshot of what they must have been doing.

The Civilizing Process

documenting this transition with an unusual database: manuals of etiquette. Today we think of these books, like

Amy Vanderbilt’s Everyday Etiquette

and

Miss Manners’ Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior

, as sources of handy tips for avoiding embarrassing peccadilloes. But at one time they were serious guides to moral conduct, written by the leading thinkers of the day. In 1530 the great scholar Desiderius Erasmus, one of the founders of modernity, wrote an etiquette manual called

On Civility in Boys

which was a bestseller throughout Europe for two centuries. By laying down rules for what people ought not to do, these manuals give us a snapshot of what they must have been doing.

The people of the Middle Ages were, in a word, gross. A number of the advisories in the etiquette books deal with eliminating bodily effluvia:

Don’t foul the staircases, corridors, closets, or wall hangings with urine or other filth. • Don’t relieve yourself in front of ladies, or before doors or windows of court chambers. • Don’t slide back and forth on your chair as if you’re trying to pass gas. • Don’t touch your private parts under your clothes with your bare hands. • Don’t greet someone while they are urinating or defecating. • Don’t make noise when you pass gas. • Don’t undo your clothes in front of other people in preparation for defecating, or do them up afterwards. • When you share a bed with someone in an inn, don’t lie so close to him that you touch him, and don’t put your legs between his. • If you come across something disgusting in the sheet, don’t turn to your companion and point it out to him, or hold up the stinking thing for the other to smell and say “I should like to know how much that stinks.”

Others deal with blowing one’s nose:

Don’t blow your nose onto the tablecloth, or into your fingers, sleeve, or hat. • Don’t offer your used handkerchief to someone else. • Don’t carry your handkerchief in your mouth. • “Nor is it seemly, after wiping your nose, to spread out your handkerchief and peer into it as if pearls and rubies might have fallen out of your head.”

22

Then there are fine points of spitting:

Don’t spit into the bowl when you are washing your hands. • Do not spit so far that you have to look for the saliva to put your foot on it. • Turn away when spitting, lest your saliva fall on someone. • “If anything purulent falls to the ground, it should be trodden upon, lest it nauseate someone.”

23

• If you notice saliva on someone’s coat, it is not polite to make it known.

And there are many, many pieces of advice on table manners:

Don’t be the first to take from the dish. • Don’t fall on the food like a pig, snorting and smacking your lips. • Don’t turn the serving dish around so the biggest piece of meat is near you. • “Don’t wolf your food like you’re about to be carried off to prison, nor push so much food into your mouth that your cheeks bulge like bellows, nor pull your lips apart so that they make a noise like pigs.” • Don’t dip your fingers into the sauce in the serving dish. • Don’t put a spoon into your mouth and then use it to take food from the serving dish. • Don’t gnaw on a bone and put it back in the serving dish. • Don’t wipe your utensils on the tablecloth. • Don’t put back on your plate what has been in your mouth. • Do not offer anyone a piece of food you have bitten into. • Don’t lick your greasy fingers, wipe them on the bread, or wipe them on your coat. • Don’t lean over to drink from your soup bowl. • Don’t spit bones, pits, eggshells, or rinds into your hand, or throw them on the floor. • Don’t pick your nose while eating. • Don’t drink from your dish; use a spoon. • Don’t slurp from your spoon. • Don’t loosen your belt at the table. • Don’t clean a dirty plate with your fingers. • Don’t stir sauce with your fingers. • Don’t lift meat to your nose to smell it. • Don’t drink coffee from your saucer.

Other books

A Buss from Lafayette by Dorothea Jensen

Heartbreaker Hanson by Melanie Marks

Baked Alaska by Josi S. Kilpack

Poems 1960-2000 by Fleur Adcock

Christmas Haven by Hope White

Revelation by Erica Hayes

The Somnibus: Book I - Finding the Mark (A Paranormal Thriller) by McGray, Craig

Haven Keep (Book 1) by R. David Bell

Viva Alice! by Judi Curtin

God Dies by the Nile and Other Novels by Nawal El Saadawi