The 1-2-3 Magic Workbook for Christian Parents: Effective Discipline for Children 2-12 (32 page)

Read The 1-2-3 Magic Workbook for Christian Parents: Effective Discipline for Children 2-12 Online

Authors: Thomas W. Phelan,Chris Webb

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Parenting, #General

lacking in one’s life, positive self-esteem cannot be bestowed instantly in a

kind, insightful moment, in a weekend workshop, or in a positive summer

camp experience. Self-esteem is based on reality, not gimmicks.

There is a story about a fourth-grade teacher—a very nice, well-

meaning lady—who was very concerned about fostering self-esteem in

her students. One day during geography, she asked the class a question:

YOUR CHILD’S SELF-ESTEEM 181

“What is the capitol of Egypt?”

One young man in the back of the room waved his hand

enthusiastically.

“Johnny?” said the teacher.

“Mississippi.” Johnny replied confidently.

Temporarily taken aback, but not wanting to injure her young student’s

developing self-concept, Johnny’s teacher quickly recovered and said,

“That’s the correct answer to another question.”

This adult maneuver is an example of a superficial gimmick designed

to protect a young boy’s self-esteem. The correct response from the teacher

should have been: “Wrong.”

The issue here is this:

Realistic and positive self-esteem is the by-

product of a life well-lived

. Living life well, in turn, is based primarily

on four things: social competence (getting along with others, feeling

loved and appreciated), work competence (for kids this largely involves

school, but it also involves independent self-management skills), physi-

cal competence (physical skills and caring for one’s body), and character

competence (ability to follow the rules, effort, courage and concern for

others). By and large, therefore, whatever you do as a parent to help your

child become competent in these areas is going to improve your child’s

self-esteem.

Our Three Parenting Steps and

Your Child’s Self-Esteem

When you began with our first parenting step, counting obnoxious behavior,

you were helping your child with her self-esteem in a very important and

basic way. No one, child or adult, is going to get along very wel with others

if she is continually arguing, whining (adults whine too!), teasing, yelling

or putting others down. Obnoxious people have a hard time making and

keeping friends. Learning self-control and not doing what you shouldn’t

is also a big part of the last self-esteem element—character.

Second, when you started systematical y encouraging positive (Start)

behavior, you were also helping your child with his self-esteem, because

Start behavior involves learning how to independently manage your life.

182 1-2-3 MAGIC

Kids who know how to get out of the house in the morning, complete

their homework, feed the dog and get to bed—on their own—naturally

feel better about themselves. Independence makes kids proud.

Finally, having a good relationship with your child—and work-

ing to strengthen that relationship—is obviously a big part of the social

competence element of self-esteem. As your kids get older and older,

they will be required to get along with more and more other children as

well as with more and more adults. In their relationship with you, your

youngsters get their critical first experience with the ins and outs of get-

ting along with somebody else.

There is another very good reason for working on your relationship

with your child: Keeping your relationship positive, enjoyable and healthy

will make the other two parenting tasks—counting obnoxious behavior

and encouraging good behavior—much, much easier.

In the next few chapters we’ll discuss some simple but effective

ways to improve and build your relationship with your children. Chapter

22 will explain how to avoid a big self-esteem killer: overparenting. In

Chapter 23 we’ll provide some helpful tips on the issues of praise and

affection. Then, in Chapter 24, we’ll have a big surprise for you regarding

the notion of family togetherness and what to do about it. Chapter 25 will

explore the ins and outs of a too-often-forgotten parental task: listening

sympathetically to the little ones. In that same chapter, we’ll discuss how

to integrate listening with counting. Turning that switch from warm to

demanding and back—again and again—is no easy task!

Key Concepts...

Healthy self-esteem is based on four elements:

1. Good relationships with other people

2. Competence in work and self-management

3. Physical skills and caring for one’s body

4. Character: courage, effort, following the rules and

concern for others

22

Overparenting

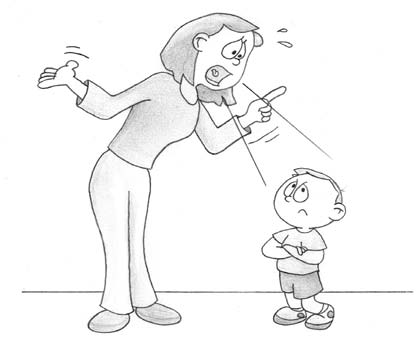

Anxious parent, angry child

Recently I was in a grocery store standing in front of the dairy case. As

I was trying to decide which kind of milk to buy, I noticed a mother

with a girl, about nine, pushing a cart and coming around the corner to-

ward me. As they came closer, the mother said anxiously, “Now watch

out for that man over there!”

I’m an average-sized adult male of about 180 pounds. There was no

way this young lady was not going to see me. Even if she had been travel-

ing at 40 miles per hour, she would still have had plenty of room to stop

before crashing into my legs. Mom’s comment was an example of what

we sometimes call “overparenting.” Overparenting refers to

unnecessary

corrective, cautionary or disciplinary comments made by parents to kids.

These parental comments can be unnecessary for several reasons:

1. The child already has the skill necessary to manage the

situation.

2. Even if the child doesn’t have al the necessary skil s to managè

he situation, it would be preferable for the youngster to learn

by direct experience.

3. In addition to 1 or 2, the issue involved is trivial.

183

184 1-2-3 MAGIC

The child can manage.

In our dairy case example above, the nine-year-old girl certainly had the

ability to (a) see me in her path, (b) appreciate the fact that it would not

be good to hit me and (c) stop the cart in time or turn away. The average

nine-year old would not need parental direction in this situation. Unfortu-

nately, when she saw her daughter heading toward me, the girl’s mother

became nervous. Though she may have actually trusted that her daughter

would not run into me, this Mom wanted to be doubly sure, so she gave

her the unnecessary, cautionary warning.

Here’s another common example of a pointless parental adminition:

“Now don’t drop your ice cream cone!” How many kids want to delib-

erately throw their tasty treat onto the ground? Not many.

Learning by experience may be better.

When our kids were little and after we moved into our first house, I used

to watch the children playing out in the yard. To my dismay, it seemed that

about every five minutes an incident would occur which I felt needed my

intervention. Then I would rush outside trying to mediate some dispute

among the children or otherwise correct the situation. Some days, espe-

cially on weekends, I would conduct multiple diplomatic missions.

Then one day my wife pointed out to me an interesting and simple

fact. She explained that during all the hours I was away from home every

week—which was well over 50 hours—no child had ever been killed,

suffered a broken arm or leg, had an eye poked out, or sustained any other

serious injury. Not only that, our kids were successfully making friends

and in general having a good time playing outdoors. The point? I was

overparenting. In the realm of neighborhood child politics, my supervision

and consulting services were not necessary. Though there were times of

social conflict, our kids were learning how to handle these new relation-

ships pretty much on their own.

The issue is trivial.

Mike and Jimmy are out in the front yard playing catch with a baseball.

Jimmy’s Dad is washing the car in the driveway while the neighbor, Mr.

Smith, is cutting his grass next door. Mike misses Jimmy’s throw and the

ball rolls over toward Mr. Smith, who smiles and tosses it back. Dad tells

OVERPARENTING 185

the two boys they will have to go somewhere else or stop playing catch.

Should Dad have kept quiet? Yes, he should have.

The issue here was truly unimportant. Dad’s oversensitivity moti-

vated him to intervene when he should have said nothing. Let the two

lads work it out with Mr. Smith, if that ever becomes necessary. The boys

were having innocent, constructive fun, and Mr. Smith probably enjoyed

trying out his old pitching arm again!

Anxious Parent, Angry Child

Though the incidents we just described are all sort of trivial, the issue of

overparenting itself is not—for two reasons: (1) parents who overparent

usually do it repeatedly, and (2) overparenting has predictable, nega-

tive effects on children. Kids will have several reactions to unnecessary

parental warnings and unnecessary discipline,

and none of these responses will be positive. CAUTION

Add these reactions up over time, and you can Parents who

have a significant negative impact on a child’s constantly verbalize

personality and self-esteem.

their worries about

The first negative reaction kids have to their kids to their kids

unfortunately accomplish

overparenting is anger. This is what we call the two things, both of them

“Anxious Parent, Angry Child” syndrome.

Anx-

bad: (1) the adults irritate

ious moms and dads who continually verbalize

their youngsters and (2)

their worries about their kids to their kids will

they undermine their

children’s self-esteem.

inevitably irritate the youngsters.

Sometimes,

of course, verbalizing a worry or concern is

necessary. “Remember to look both ways before

crossing the street,” said to a four-year old who doesn’t have that skill

yet, is necessary for the child’s safety.

It’s the consistent and pointless repetition of worries that aggravates

youngsters. Why do kids find this repetition aggravating? In short, because

it insults them. The parent’s basic message is this: I have to worry about

you so much because you’re incompetent; there’s not much you can do

on your own without my supervision and direction. No child likes to be

put down, and overparenting is definitely a put-down.

That point leads us to the second negative reaction children have to