Prisoners of the North (23 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Leopold M’Clintock, whose successful discovery of Franklin relics on King William Island brought an end to the great search. He is shown here as a rear admiral

.

In July 1858, M’Clintock at last reached Beechey Island where the graves of three of Franklin’s men had been found. He erected a suitable stone tablet in their memory and set out to manoeuvre his little yacht down Peel Sound in the direction he was sure Franklin had taken. When a dike of ice barred his way, he headed instead down Prince Regent Inlet, hoping to make his way into the sound through the narrow channel of Bellot Strait. Six times he tried to force his way through; six times the ice pushed him back. In September he got through as far as the western mouth of the strait when another belt of ice blocked his way. He spent the winter of 1858–59 in a sheltering inlet at the eastern end.

That winter he laid out depots for three sledging expeditions. One would explore Prince of Wales Island. Another would scour the delta of the Great Fish River and the western shore of Boothia. The third would search the north coast of King William Island. Somewhere in that chill and treeless region M’Clintock was certain they would find evidence of the lost expedition.

He was right. Tantalizing clues began to turn up—first an Inuk wearing a naval button, then an entire village where the inhabitants had buttons, a gold chain, silver cutlery, and knives fashioned of wood and iron from the wrecked ships. One native had seen the bones of a white man who had died on an island in the delta of the Great Fish River; others recalled a ship caught in the ice to the west of King William Island. M’Clintock and his deputy, Lieutenant William Hobson, were told of two ships the Inuit had seen, one sunk and one badly broken. White men had been seen, too, hauling boats south to a large river on the mainland.

Soon on their sledging forays they came upon further evidence: silver plates bearing the crests of some of the officers and tales of white men who had dropped in their tracks as they headed for the Great Fish River. In late May, M’Clintock came upon a human skeleton, the body face down, as if its owner had stumbled and dropped forward where his bones lay. And finally, there was a note from Hobson, who had discovered the only written record ever found of the lost Franklin expedition.

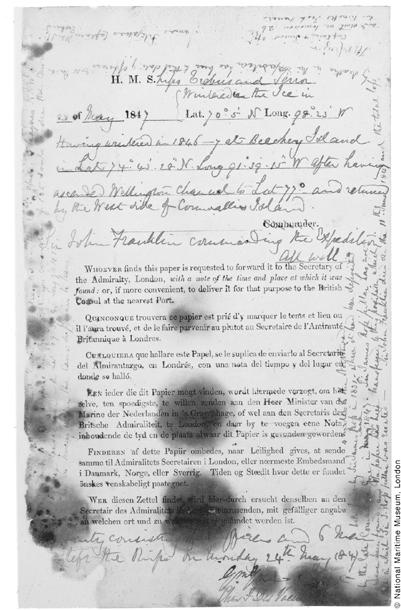

In a cairn at Victory Point, Hobson had found a message written on a naval form dated May 28, 1847. It showed that the lost ships had indeed gone up the Wellington Channel, circled around, and wintered at Beechey Island. They had been beset in the ice stream just northwest of King William Island. Lieutenant Graham Gore had taken a party ashore and left the message, certain that their ships would shortly be freed to make their way through the Passage.

Scrawled in the margin of this cheery note, a second message, written a year later on April 27, 1848, told a more sober tale. Franklin had died the previous June; the ships had been trapped in the ice for nineteen months; and nine officers, including Gore, and fifteen men were dead. This added to the mystery. No other polar expedition had suffered such a devastating loss.

The survivors had abandoned their ships and were now trying to reach the Great Fish River. Most didn’t make it. On King William Island’s northwest coast, M’Clintock came upon a massive sledge with a pitiful load of useless articles: books, soap, sheet lead, crested silver plate, dinner knives, a beaded purse, watches, and a cigar case, “a mere accumulation of dead weight, but slightly useful and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge crews” in M’Clintock’s description. On top of the sledge was an eight-foot boat and inside it, two skeletons. Thus far had they stumbled and no farther.

When they set off in May 1845, Franklin’s two ships had been stocked with three years’ supply of provisions that could easily be stretched to five. What had happened? In the intervening years, three causes have been identified as the roots of the mass disaster: scurvy, lead poisoning, and botulism.

Scurvy, brought on by a deficiency of Vitamin C, had been recognized since the days of Captain Cook. It was traditionally cured by regular doses of lemon or lime juice (which was the reason that Englishmen were universally known as “limeys”). What was not known, however, was that the citrus juice lost its potency after a year or so. Equally important was the lack of fresh meat or fat aboard the navy ships, another source of Vitamin C, which Stefansson learned from the Inuit but which the British, who believed in meat preserved in salt, ignored.

Found on King William Island, this form provided the only written clue to the fate of the Franklin Expedition. The scribbled phrase “all well” was premature

.

A second cause of death was indicated when the bodies of three of Franklin’s men were exhumed from their graves on Beechey Island and subjected to scientific investigation. Owen Beattie and John Geiger discovered that all three had suffered from lead poisoning, apparently from badly soldered tins, a suspicion confirmed by some three thousand empty tins surrounding the Franklin camp. The canning process was in its infancy; tins were soldered not by machines but by human hands. The percentage of lead found in the dead men’s bones was four or five times that of a normal Englishman of the day. The three men did not die of lead poisoning; it was probably pneumonia that killed them. Nonetheless, they would probably have suffered the debilitating physical and mental effects that lead can cause had they survived after Beechey.

The third cause of death was botulism, present in badly tinned and undercooked provisions. The two villains here were the victualler, Stephen Goldner, who cut every corner possible in order to underbid competitors, and the navy itself, which in the interests of saving money did little to inspect the tinned meats, soups, and vegetables that were being supplied to it, usually at the last moment, by the rapacious Goldner. Bones and offal went into tins with meat. Horsemeat was often a substitute for beef. Quantities of dust entered the tins along with the vegetables. Gravy was diluted and all efforts at preservation were frustrated by inadequate cooking. As a parliamentary inquiry later established, little or no attempt was made to look into Goldner’s shoddy methods.

Botulism is an invisible killer—tasteless, colourless, odourless—that can strike suddenly and unexpectedly. It can taint food and make it smell rank, but then, all the food on Arctic vessels smelled and tasted foul after a few months. The toxin can be killed by heat—by hard boiling or hard frying—but when the ships were held up by the ice pack, coal for cooking was the first sacrifice made. It is thus clear why so few men died in the first years of the expedition. Later, the sledge parties that left the ships used what fuel was available to melt snow, leaving little to heat up tins of Goldner’s tainted supplies.

“The canning provisions—supposedly advanced—were a chimera,” Scott Cookman reports in

Ice Blink

, after poring through the records of the select committee of the House of Commons that finally investigated Goldner’s contracts and eventually put him out of business. “The latest patented methods leached them of nutrients but left them tainted with bacteria and viruses. The canning process contaminated them with lead and arsenic. Soldered shut to prevent admittance of the ‘atmospherics’ believed to cause spoilage, they were in fact death capsules packed with

Clostridium botulinum.”

Franklin himself had probably not succumbed to these afflictions but died of pneumonia or some similar ailment typical of advancing years. In a postscript to a letter to Jane Franklin on his return, M’Clintock went out of his way to assure her that her husband had clearly not suffered long and had died just as success was in sight.

On hearing the news of M’Clintock’s finds she had returned from the Pyrenees, where her doctor had sent her for her health, to find herself famous. The

News of the World

published one of the many letters her admirers sent in, this one titled “The Good Wife’s Expedition”:

Since the beginning of the world, it has been considered that a good woman is the best thing to be found.… This is not a frothy compliment, for the world has before it at the present moment the living woman who deserves it, to contemplate, to admire and to bow down to with all the homage and devotion that a human being may bestow. There is a Lady Franklin to extol.…

With her husband’s death firmly established, the widow accelerated her campaign to ensure his place in history as

the

discoverer of the Northwest Passage. She had wanted a national monument to the crews of the lost ships placed in Trafalgar Square, but apart from what her biographer calls “a niggardly tablet” at Greenwich, the government declined to act. One thing, however, was certain: any memorial or monument must record the fact that Sir John had been the first to discover the Passage. Meanwhile she spent her time badgering Members of Parliament to make sure that the officers and the crew of the

Fox

would be reimbursed. Her behind-the-scenes efforts were successful; Parliament voted them five thousand pounds. When the Royal Geographical Society presented M’Clintock with its Patron’s gold medal and Lady Franklin with its Founder’s gold medal—the first to a woman—the inscriptions made it clear that her husband’s expedition took precedence as the discoverer of the Passage.

This was her crowning achievement. Everything she had struggled for was now accomplished. For more than a decade her ambitions for her husband had held her captive. Now, it was as if she had been released from a long incarceration. At last she could indulge in the one passion she had denied herself. She could travel the world (at least to the warmer climes, for she had no interest in frozen landscapes) and gratify her wanderlust. She would go to America at the behest of Henry Grinnell, with whom she had conducted a warm correspondence for a decade.

She set off with the faithful Sophy Cracroft in tow in July 1860 on what might be described as a triumphal tour—a succession of banquets, state dinners, presentations, and receptions. They crossed the Atlantic; stopped at New York; went on to Canada, where she had an audience with another visitor, the young Prince of Wales; sailed from New York to San Francisco; then on to Rio de Janeiro, where she met the Emperor of Brazil; then to Chile, where she rode about in a bullock cart; back up the coast, through Panama, to San Francisco again; and then on to British Columbia, where a group of Indian paddlers took her by canoe up the turbulent Fraser.

On their return to California, she and Sophy embarked on the liner

Yankee

for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), which she had visited following her husband’s departure from Van Diemen’s Land. Here she was the guest of King Kamehameha IV and his queen, Emma, who was so entranced that she could hardly be induced to step into the carriage before Jane, of whom she declared, “With Lady Franklin I would go anywhere—even as a servant.” Jane and Sophy toured the islands, the king himself providing his own boat and crew to use as they wished. They clambered down the great crater of Kilauea and paid their homage at Captain Cook’s monument before returning to a well-appointed state dinner in their honour.

Everywhere she went, Lady Franklin was treated with regal pomp. On Maui, the people believed she was the queen of the English. At a royal reception held to mark the anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession, the guests were presented to her as if she were royalty; the bows made to her were even lower than those for royalty themselves.

Hawaii was not the end of her peregrinations. The Far East beckoned, and off she went with Sophy to Yokohama and Nagasaki and then on to Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore, and Penang. Their last stop before returning home was Calcutta, where they dined with Lord Elgin, the new viceroy of India.

When Jane Franklin returned to England in the summer of 1862, just before her seventieth birthday, she had been away for two years. Those long months of travel had not exhausted her; on the contrary, she had thrived. A friend reported that he had never seen her looking “so well, young and blooming.” Now for the first time she had a house of her own—in Kensington, complete with a little garden that gave it a charm unique in London. A celebrity herself, “the most extensively travelled Lady in Great Britain,” in the words of the publisher John Murray, there were few of the famous she could not meet if she wished, for she was considered “the great gun of the season.”

Now in her eighth decade, she was still active. Queen Emma, at her invitation, had arrived on a visit that occupied much of her attention. Then, in 1865, there was “a fearful working up of the slumbering past,” in Sophy’s words. News came from the Arctic that Charles Francis Hall, the Cincinnati newspaper-publisher-turned-explorer, had learned from the Inuit at Repulse Bay that some of the members of the lost expedition were still alive. There was considerable argument among the Arctic experts about this report, but she could not dismiss it. “It is our bounden duty, as it is an impetuous instinct,” she wrote, “even though we may feel shocked at the sight of skeletons rising in their winding-sheets from their tombs.… I believe Hall is doing exactly what should have been done from the beginning, but which no Government could

order

to be done.” But since Hall was still in the North and out of touch, nothing for the moment could be accomplished. She herself, at the age of seventy-five, was on her way to India.