Prisoners of the North (24 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

For the English she continued to be a major attraction. She was late for her train at Charing Cross; no matter—it was held for her. At Dover, Sophy noticed that men were continually taking off their hats to her aunt. Her Indian sojourn, exacting as it was, came as a tonic. She travelled from place to place, often by bullock cart and once on the back of an elephant. On one day she made a thirteen-hour journey with only a half-hour break. En route home from Bombay, at the site of the half-finished Suez Canal she met its builder, Ferdinand de Lesseps, who himself took her and her niece on a tour of the big ditch.

She was back in England with Sophy in time to watch the unveiling in November 1866 of a national monument to her husband at Waterloo Place. The following year she was off again on what her biographer calls “a breathless career of sightseeing,” the highlight of which was an audience with Pope Pius IX at the Vatican. “There had been difficulties in giving an audience to my Aunt on Thursday,” Sophy confided to her diary, “but it was felt that every possible favour shd be done to the widow of the good Sir John Franklin.” His Holiness even paid her the striking compliment of advancing a few steps to meet her and “expressed his great pleasure in receiving her who was so well known & honoured as a devoted wife.…”

In England she was pressed to follow up Hall’s reports by organizing a new British expedition to Repulse Bay, but she confessed to “a dread of future heart-rending revelations whether true or false.” One gets the impression that she had finally put that obsession behind her. Instead, she set off for India once more, riding through the narrow streets of Benares on the back of the Rajah’s monstrous elephant. At Delhi, she and Sophy made a four-hour drive to view the red sandstone minaret Kutb Minar, 238 feet high. “I need not say,” Sophie admitted, “that we went to the top.” Jane walked determinedly around the topmost small platform, but that, Sophy confessed, “my head would not bear.”

On Jane’s return to England the past again awaited her. She was startled by a small paragraph in

The Times

reporting that Charles Hall, after five years in the Arctic, had discovered the skeletons of several of Franklin’s men on King William Island and had brought numerous relics with him to the United States. Once again she was moved to take action. She wanted another search made with Henry Grinnell’s help, and she wanted to see Hall herself: “Having failed in my last effort to get any experienced Arctic officer to examine him personally we are compelled to feel that we must go now to America ourselves.”

By late April she was back, with Sophy, in San Francisco, which she detested, and taking a ship to the formerly Russian town of Sitka on an island off the Alaska Panhandle, the most northerly point in all her travels. She had apparently retained some hope that documents from her husband’s expedition might somehow have reached the old Russian capital. She and her niece arrived on May 19, 1870, at the charming and picturesque little community (as it still was when I visited it in 1932), recently acquired from the Russians by the United States.

In Sophy’s journal there is no word about any missing documents and no suggestion that they even searched for any. Was that really their reason for travelling north? Or was it simply a vague excuse to justify Jane’s wanderlust? She wasn’t much more than a year away from her eightieth birthday and still on the move. They spent an enjoyable month in the former headquarters of Alexander Baranov, the rum-swilling Lord of Alaska, and then moved on, this time to Salt Lake City, where she indulged her fascination with Mormonism, especially its polygamous aspects. From there they moved on to Cincinnati to meet with Charles Francis Hall in July and then to New York in August with Hall to visit Henry Grinnell, who, she hoped, would persuade Hall to change his plan to go to the North Pole and instead join in “the so holy and noble cause as the rescue of those precious documents from eternal sepulture in oblivion.” Hall was prepared to help her but only after he had achieved the Pole, a triumph that eluded both him and those who followed for forty years.

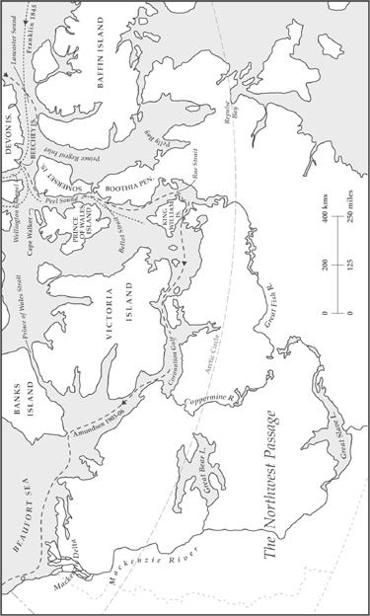

Sometime after she returned to London, the occasion of the death of Robert McClure revived an old controversy. In October 1850, McClure had actually seen the Passage, or more accurately,

a

passage, following his exhausting sledge journey along the eastern shore of Banks Island to Prince of Wales Strait. There, as his colleague Alexander Armstrong declared, “the highway to England from ocean to ocean lay before us.” It had generally been assumed but not proven that some of Franklin’s dying crew had viewed one of the routes through the frozen passage from King William Island, but McClure’s discovery was indisputable. Now, at the age of eighty, it behooved Lady Franklin to support her claim that her husband was the real victor in the long search. Allen Young, who had been sailing master on the

Fox

, was preparing an expedition of his own to accompany the North Pole expedition of Sir George Nares. His plan was to break away from the major expedition and turn south to Peel Sound, seeking records of

Erebus

and

Terror

. But money continued to be a problem. Jane Franklin reminded the whaling fleet that a three-thousand-pound reward she had put aside earlier as a prize for the recovery of such records was still in force. Her well-publicized announcement contributed to a new wave of excitement on both sides of the Atlantic and the usual spate of crank letters, including “a proposal from a Mr. Ralph Scott to carry out an invention of his for rising into the air.”

It also brought an offer from James Gordon Bennett, Jr., of the New York

Herald

(the paper that had sent Stanley after Livingstone) to put up five thousand pounds for Allen Young’s expedition if one of his correspondents could tag along. In May 1875, Young’s expedition set off, financed largely by Bennett and Lady Franklin herself. By this time, however, she was seriously ill of “a decay of nature” and prayers were being said at her request in both America and England.

She was not a model patient, although the press described her condition as “sinking.” She refused flatly to take her medicine, and when a glass was offered to her, she flipped it away, settling back on her pillow with the ghost of a laugh. She hung on for three more weeks and went to her grave in a casket borne on the shoulders of six Arctic explorers. She died a fortnight before the memorial to her husband could be unveiled in Westminster Abbey, too weak to compose the inscription on the cenotaph. Her uncle, the poet laureate Alfred Tennyson, did it for her:

Not here! the white North has thy bones;

And thou, Heroic sailor-soul

,

Art passing on thine happier voyage now

Toward no earthly pole

.

Hers was a remarkable achievement. Through her own obstinacy and firm will, she transformed a plodding and unexceptional naval officer into a British saint.

To the left of Franklin’s bust, the dean, S. P. Stanley, had arranged for an inscription:

To the memory of Sir John Franklin, born April 16, 1786, at Spilsby, Lincolnshire: died June 11, 1847, off Point Victory, in the Frozen Ocean, the beloved chief of the crews who perished with him in completing the discovery of the North-west Passage.

That was what she had fought for—that the memory of her husband would be tied irrevocably to the achievement of what had been called “the greatest prize in the history of maritime exploration.” With that accolade engraved in stone, the persevering Lady could truly rest in peace.

CHAPTER 4

The Hermit of the Tundra

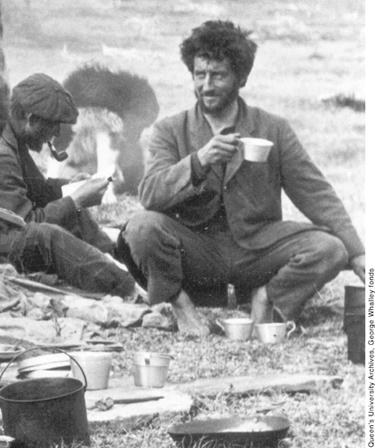

John Hornby in the Great Bear Lake country, 1912, consuming endless cups of tea

.

—ONE—

John Hornby, who died slowly of starvation in April 1927 in the heart of the Arctic desert that Samuel Hearne dubbed the Barren Ground, is perhaps the most frustrating figure in the history of the North. If he is a legend today it is largely because he worked at it—worked at being an eccentric, worked at being an outsider, worked hard at portraying himself as a rugged survivor who welcomed hardship and laughed in the face of danger. Who else would choose to spend a winter in the most inhospitable corner of Canada just to be able to boast that he had done it?

He had no other purpose in his life. He wasn’t a prospector and could hardly tell a gemstone from a chunk of granite. Nor was he an explorer; he was not interested in seeking out new lands and was wary of those who did because he feared they would import civilization into his untrammelled wilderness. He was a competent trapper, but he made scarcely a nickel from furs because he couldn’t concentrate on his traplines and was too slovenly to take proper care of the hides he did garner.

The Barren Ground obsessed Hornby. In his mind, it was his property, and like a lovesick suitor he was jealous of anyone who tried to invade that land above the treeline. But what did he see in this desolate domain? Where was the attraction? Indeed, only a handful of explorers have crossed this empty plain that stretches from the forests that screen the Mackenzie to the shores of Hudson Bay, a “monotonous snow-covered waste,” in the words of Warburton Pike, one of the earliest of the tundra explorers, “without tree or scrub, rarely trodden by the feet of a wandering Indian.” In Pike’s description, “a deathly stillness hangs over all, and the oppressive loneliness weighs upon the spectator until he is glad to shout aloud to break the awful spell of solitude.”

This is the domain that Hornby chose for himself, the one in which he felt secure from a world he thought had gone crazy. It is a topsyturvy land that has not yet recovered from the ebb and flow of the overwhelming ice sheets that dislocated the ancient drainage pattern, diking lakes with mounds of rubble, gouging out new rivers, choking others, and scattering debris from one end of the North to the other until the whole lake and river system was out of kilter. From the air, the Barrens in summer are an endless rolling desert of brown suede, stippled with thousands of tattered little lakes and marked by the occasional cyclopean boulder, as big as a house, dragged for hundreds of miles to rest on the slopes of the western mountains.

They call it a “cold desert” because the precipitation is less than five inches a year and the evaporation almost non-existent. If the permafrost that imprisons the little lakes should ever thaw, the Barrens will be another Sahara.

Here, too, as Hornby discovered, one finds the bizarre geological formations known as eskers—high ridges of sand and gravel looking like railway embankments, some a hundred feet high and a dozen miles in length, their crests flattened by the hooves of thousands of migrating caribou. These snake-like ridges, which provide the only shelter from the winds that howl across the treeless plains, are deposits of sediment made by streams of meltwater that flowed in tunnels under the ice when the glaciers were decaying. It was in a dugout in one of these eskers that Hornby and a companion took shelter for an entire winter.

The Barrens made him and in the end the Barrens destroyed him. He would have had it no other way. As an early biographer has put it: “Without the Barrens there could have been no Hornby. Without them, he would have been a misfit—one of society’s drop-outs.” The settled world was not for Jack Hornby. “You can fully realize how miserable I feel here,” he wrote from England to a former partner between forays into the tundra. “This senseless life is detestable. How can people feel justified in leading an aimless existence?”

Yet Hornby himself led an aimless existence, wandering about the North without any real objective, usually ill-prepared and ill-equipped for misfortune or disaster. He liked it that way. As his erstwhile companion Captain James Critchell-Bullock put it, “No argument could persuade Hornby that any Arctic or sub-Arctic explorer was worthy of consideration unless the principals have gone out on a shoestring and returned by the skin of their teeth.”