Prisoners of the North (20 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Franklin wanted out but was subjected to a further embarrassment when a newspaper arrived from England reporting that a new lieutenant-governor had been gazetted to replace him. It was two months before an official dispatch (already six months old) arrived to inform him that his term was at an end. By then his replacement had arrived. A lackadaisical colonial office and the primitive state of the overseas postal system had put him in an impossible position.

“

GLORIOUS NEWS!

” the

Colonial Times

exulted. That was the reaction of the establishment’s anti-Franklin press, but the people of Van Diemen’s Land did not agree. In January 1844, a crowd of two thousand well-wishers cheered the pair off when they embarked for England; more than ten thousand signed an address of farewell. A decade later, when Jane Franklin appealed for funds to help search for her lost husband, the Tasmanians contributed seventeen hundred pounds.

The entire experience had devastated them both. Franklin himself was close to a breakdown, and Jane was in a state of nervous prostration. How they must have wished they had accepted the lesser posting in Antigua! Now nothing would do but that the polar hero should tell his own side of this sorry tale in a pamphlet that few bothered to read. In England his Tasmanian troubles were small potatoes. He was still a hero to the public and to his Arctic cronies. But that wasn’t enough for him and it wasn’t enough for Lady Franklin. His honour was at stake, or so he believed. Some new feat of exploration was required to remove the stain of Montagu’s perfidy. He had reached the nadir of his career, and his sixtieth year was approaching; he could not rest until he had redeemed himself. On his return to England he would, with his wife’s exuberant support, launch a new expedition to discover the Northwest Passage.

—TWO—

Had Sir John Franklin accepted the original offer of a governorship in the Caribbean, the history of Arctic exploration might be remarkably different. The Great Search for his missing expedition, much of it instigated by the importunity of his persevering wife, dragged on for more than a dozen years. More than fifty ships were engaged in that search, untold funds were squandered, and lives were sacrificed in a hunt that covered the frozen world from Alaska to Baffin Bay. The Great Search also lifted the curtain over a labyrinth of islands that had been unexplored before it began.

Franklin’s return to England in 1844 coincided with a new flurry of interest in the Northwest Passage, stimulated by John Barrow, Jr., the Admiralty bureaucrat responsible for England’s great age of naval exploration. For fifteen years, from 1818 to 1833, no fewer than nine expeditions had been mounted by the Royal Navy to seek out this will-o’-the-wisp, making Edward Parry, John Ross, and Franklin the heroes of their days. None had been successful and interest in polar exploration was fading when James Clark Ross (John’s nephew) and Francis Crozier returned in 1843 from a record-breaking voyage to Antarctica in two vessels especially built for polar travel,

Erebus

and

Terror

. They had penetrated farther south into the Antarctic region than any before them and were the talk of England. Barrow seized on the interest raised by this expedition to prepare detailed plans to use the same vessels to renew the search for the fabled Passage before some other nation beat the British to the prize.

The hope for some sea route linking the Atlantic to the Pacific went back to the fifteenth century, when it was seen as a shortcut to the riches of the Orient. As new discoveries caused the search for it to be moved farther and farther north, its practical value dwindled. What Barrow was seeking was an essentially useless channel (or series of channels) blocked by formidable barriers of ice and virtually unnavigable. As Francis Spufford has pointed out, more expeditions have managed to travel safely to the moon and return than had been able to navigate the Passage from sea to sea.

Sensible considerations did not weigh on Barrow, to whom the Passage was a symbol of all that was pure, noble, and courageous in Arctic exploration. Spufford quotes from Barrow’s digest of exploration narratives, which he published in 1846 after his retirement. In it he singled out the moral accomplishments of the explorers—the way officers “exhibited the most able and splendid examples of perseverance under difficulties, of endurance under afflictions, and resignation under every kind of distress.” That fitted the Victorian attitude toward morality. The Passage was seen as a glittering prize, but no longer for sordid commercial reasons. Discovery was venerated for its own sake. The Passage was to be conquered simply because it was there.

Franklin pushed hard to lead the proposed new expedition to search out the Passage, and his friends pushed too. His honour was at stake; the only way to restore it would be action in the pure, clean environment of the Arctic channels. As Parry put it to the navy, Franklin would die of disappointment if he didn’t get the job. James Clark Ross was the logical choice, but he bowed out on what looked like a thin excuse: he didn’t want to be separated from his new bride. That said, Jane Franklin did not lose the opportunity to play upon Ross’s friendship for her husband and his sympathy with his situation. “If you do not go,” she wrote to him, “I would wish Sir John to have it … and not to be put aside for his age.… I think he will be deeply sensitive if his own department should neglect him.… I dread exceedingly the effect on his mind.…”

Franklin was now an old man by the standards of the day. The Admiralty was doubtful, but the explorer’s old Arctic comrade from an overland expedition, Dr. John Richardson, offered to sign a medical certificate indicating that his health was sound enough for any journey through frozen channels. Franklin admitted that he was too plump for overland travel but pointed out that the entire voyage would be by ship. His superiors sympathized, and in the end the Arctic explorer got the job because his friends felt sorry for him.

In February, Franklin’s appointment was confirmed. The

Erebus

and the

Terror

would be the first ships in Arctic records to operate using adapted railway locomotive engines of twenty horsepower each and screw propellors. On board would be ample provisions for three years, which, Franklin claimed, could be stretched to five if necessary. There was no attempt to plan for unforeseen emergencies. No relief expeditions were contemplated since Franklin feared if they were the Admiralty might scrap the whole idea.

In the exuberance that marked the venture only two critical voices were raised. Old John Ross, the crusty Arctic survivor, wondered why so many men were needed to trace the Passage. This was the largest expedition so far to invade the polar world—134 men on two big ships. Ross thought one smaller steam vessel would be cheaper and more efficient, and he was right. When the Passage was finally conquered just over half a century later, Roald Amundsen succeeded with a single small schooner and only seven men. Ross urged Franklin to leave depots of provisions and perhaps a boat or two at various points, should he be trapped or wrecked, a sensible piece of advice that Franklin dismissed as an absurdity.

An eccentric surgeon-naturalist, Richard King, who had written a book on the Arctic coast, also had his reservations. The best way to find the Passage, he insisted, was to take a party of no more than six men overland along the coastline from the mouth of the Great Fish River. But King was ignored by the naval hierarchy who were committed to cumbersome sea voyages in large ships—the larger the better.

On May 19, 1845, the expedition set off. Aboard the

Erebus

, John Franklin’s daughter by his first marriage, Eleanor, noticed that a dove had settled on one of the masts. “Everyone was pleased with the good omen,” she told her stepmother, “and if it be an omen of peace and harmony, I think there is every reason of its being true.”

Jane Franklin’s niece, Sophy Cracroft, was beside her aunt on the pier to wave one last goodbye as Franklin signalled his farewell with a handkerchief. His only worry was his wife. Could she endure his absence? From Sophy he had extracted a promise: that she would stay by her side until he returned. For the next thirty years the faithful niece rarely let her aunt out of her sight, travelling in her footsteps from Hong Kong to Sitka, Alaska, and rejecting all suitors who might have interfered with what she considered a higher cause.

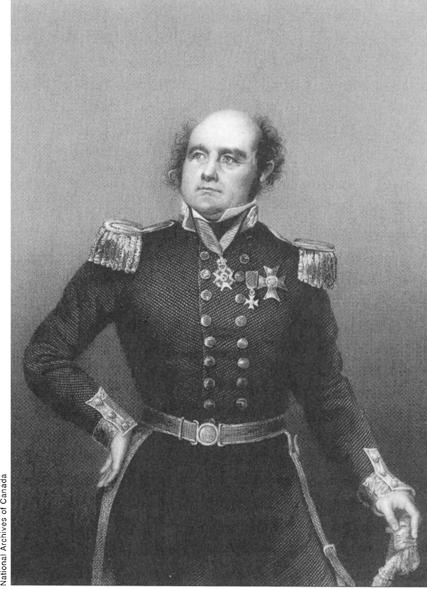

Sir John Franklin as he looked at the height of his fame

.

And so they waited, spending their winters in England, expecting news from the Arctic, and their summers abroad: in France (whose government listed Franklin’s name at the Rouen Customs House as among the world’s most famous navigators), and in the West Indies and the United States, where Lady Franklin performed her usual round of inspecting hospitals, schools, factories, and other institutions and also managed to climb Mount Washington.

In spite of this hectic itinerary she could not take her mind off the Arctic. “We have now given up all expectation of hearing from Papa this year,” Eleanor wrote to a friend. “In October or Novr next I trust we shall either see or hear from him.”

To old John Ross, Jane wrote, “I dare not be sanguine as to their success—indeed the very thought seems to me presumptuous, so entirely absorbed is my soul in aspirations for their

safety

only.” And, if they didn’t come back as planned, would Ross be the man to go in search of them?

Ross, whose earlier skepticism in 1844 had caused him to promise Franklin that he would mount a search if needed, wrote to the Lords of the Admiralty that if Franklin hadn’t managed to reach Bering Strait by this time, his ships must be imprisoned in the ice. He wrote again the following month suggesting that it was time to take steps for relief; but the Admiralty fobbed him off, declaring that they would offer rewards to Hudson’s Bay traders and whalers to be on the lookout for the expedition, and that was all.

In June, the difficult Dr. King again entered the picture. He asked the Colonial Secretary for permission to follow the Great Fish River and guide members of the missing expedition who might have, he thought, been forced to abandon their ships, to depots of food. King, not being a navy man and considered a bit of a nuisance, which he was, got nowhere. “I do not desire that he be the person employed,” Jane Franklin told Ross, who had volunteered to lead a rescue expedition that the government was belatedly considering. At the very least, she hoped, the government would authorize the Hudson’s Bay Company “to explore those parts which you … cannot immediately do.” As Ms. Woodward has argued, if King’s experience and Jane’s instinct had been immediately followed, some of Franklin’s men might have been rescued.

Sir John Franklin in middle age, an old man by the standards of his day

.

But though time was running out, the navy dawdled. Franklin had three years’ supplies when he sailed for the Arctic in 1845. Belatedly, in January 1848, the little supply ship

Plover

set off for Bering Strait carrying more supplies for the missing ships, only to be delayed for a year in transit. With

Plover

went a letter from Jane, who warned her friends not to write anything “that can distress his mind.… Who can tell whether they will be in a state of body or mind to bear it.” The letter was returned as were the others she dispatched over the next several years. Meanwhile, Sir John Richardson was heading off on an overland expedition to examine the north coast of the continent from the Mackenzie estuary to the Coppermine. She wanted to accompany him but was dissuaded from that venture. “It would have been a less trial to me to come after you,” she wrote to Franklin in a letter that was returned, “as I was at one time tempted to do, but I thought it my duty & my interest to remain, for might I not have missed you & wd it have been right to leave Eleanor—yet if I had thought you to be ill, nothing should have stopped me.” Instead, she put up her own money—three thousand pounds—as a reward to any whaler who might find the lost expedition.

In May 1848, the government’s own search expedition—two big ships,

Enterprise

and

Investigator

—finally set off under the overall command of James Clark Ross, who had reversed his firm decision never to go north again. As usual it carried a letter from Jane: “My dearest love, May it be the will of God if you are not restored to us earlier this year that you should open this letter & that it may give you comfort in all your trials.… I try to prepare myself for every trial which may be in store for me, but dearest, if you ever open this, it will be I trust because I have been spared the greatest of all.…”