Prisoners of the North (27 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Though it was six months before he could stand upright, he was faced with struggling every second day to get a fish net through the ice, three miles from his cabin. This was his only source of fresh food. It turned out to be the coldest winter on record with the temperature reaching −70 degrees Fahrenheit. In a letter to Douglas written the following summer, Darcy Arden described Hornby’s plight: “He is not fit for this country now. The war has affected poor Hornby very much and he is not the man like he was when you were here before. Some time last March I went over to see him and found him starving and completely out of his head. I think if he stays at the lake this winter something will happen to him.”

Hornby welcomed hardship and put himself, apparently deliberately, into situations where the absence of food became a way of life. “No one but Hornby would live in such discomfort in the Northland,” Denny LaNauze, the Mountie inspector, once remarked. Hornby’s movements during the winter of 1918–19 were driven by aimless hunts for caribou, ranging from various points in the Great Bear Lake area to the big bend of the Coppermine. But he was finally finished with Bear Lake; he never wanted to see it again; it invoked too many unhappy memories. In the spring he left it for good. He headed out to Edmonton but got no farther. “The post-War flurry irked me,” was the way he put it. He dawdled before going north again, this time by way of the Peace, but he had left too late in the season and found himself frozen in near Chipewyan. He spent that winter in an enlarged wolf den.

The Barrens continued to engross him, to occupy his imagination, and to haunt his mind. Why? What was it about this bleak and friendless land that bewitched him? Apart from the few glimpses caught during his trips down the Coppermine, he had very little knowledge about the tundra and virtually no experience. Yet here he was, musing about spending a winter alone in an unforgiving realm that even the native Indians avoided. That, one suspects, was its appeal for Jack Hornby. He would do something few men had ever done in the history of the North, and if his ambition was fulfilled, he would be applauded for it. Hornby belonged to those among us who have a dream. With some it is an acceptable vision: to make a million, to write a masterpiece, to swim the English Channel, to scale a mountain peak. Hornby’s dream was unique: to live alone in the Barrens—alone and free—to thumb his nose at civilization, to seek out and revel in all the hardships this bleak and windswept terrain had to offer.

When spring came his plan was to travel east by way of Great Slave Lake from Fort Resolution to Fort Reliance at its eastern end, a distance of some two hundred miles. After that he would make his way by Artillery Lake to the tundra. At Fort Smith he organized supplies for the venture—two outfits, one for trapping white fox or valuable furs, one for trading. He set out in June and reached Fort Reliance in September. The Indians were off on their seasonal caribou hunt, leaving Hornby to build his winter quarters, a small cabin, six by eight feet, directly across the bay from the chimneys of the original fort put up by the Arctic explorer George Back in 1833.

He really had no firm idea of what he would do or how he would fare after he left the shelter of the treeline. He was supremely confident that he could live off the land, but he had made no preparation to do so. He did not even understand the migrations of the caribou, which are the key to existence on the Barren Ground. He did not take into account the possibility of accident or injury, nor did he realize that he had chosen an unlikely region in which to justify his theories. He had settled upon a poor place for caribou and also for fishing. Worse, with winter coming on and his cabin yet unfinished he was taken ill, unable to lay out his nets. When at last he had recovered enough to finish his new quarters and had just started trapping, the accident-prone hermit fell against his small tin stove and burned his leg badly.

Ill luck continued to bedevil him. He finally managed to mount a four-day caribou hunt, but that proved fruitless. When he returned he found the Indians had come back in his absence and looted his cabin, leaving him only a meagre supply of food and one pair of snowshoes. He and his dogs were reduced to living on bannock and the small trout that he found in his nets.

“I am now practically destitute,” he told his diary in January. In order to get enough bait for his traps he would have to hunt for caribou. But that took time and energy, and in the meantime he was forced to feed his dogs from his supply of staples. Now he admitted, “The urge to get fur blinded me to the consequences of running short of supplies.” At that point he was down to fifteen pounds of flour and only enough fish from his nets and hooks to feed the dogs and himself for a single day. To stay alive he would need between twelve and fifteen pounds of fish each day, but his right arm was partly paralyzed and his right hand badly swollen from a neglected injury. Chopping wood was painful and his fishing ground was three miles away.

It was bitterly cold. He had no skin clothing, and he was losing the body fat that might have kept him warm: he was little more than a walking skeleton, reduced to skin and bones. His dogs were also growing weak on a starvation diet. On February 23, he scrawled a wan note in his diary: “No trout, no bait, no caribou, nothing.” And outside his cabin a fierce blizzard was blowing.

The bad weather continued, making it impossible on certain days to visit his trapline or his fishing ground. When he did, he often found nothing. On March 6, two days after his biggest dog died, he told his diary: “At times this life appears strange. I never see anyone, no longer have anything to read, and my pencil is too small to permit me to do much writing. It is not surprising that men go mad.” There is no self-pity here, no wail of despair; Hornby was merely examining a way of life he had chosen for himself and commenting upon it.

A few Indians came and went. They too were starving: that was their way of life. Hornby fed them fish when he had any. On March 11, he came in from examining his rabbit snares and collapsed on the cabin floor, too weak to reach his bed. Yet his powers of recuperation were remarkable. Two days later he was out again and after twelve hours returned to his cabin with a whitefish and a fox. In this hand-to-mouth fashion the days dragged on. Spring came; the fishing improved. On June 17 he gorged himself on a thirty-pound trout, but there was no way in which he could accumulate enough for the daily hundred pounds he would require for the next season. Although his plans to establish himself on the Barrens by way of Artillery Lake were dashed, he still clung stubbornly to his original dream. Now that the ice was breaking up he would return to Fort Resolution for more supplies; then, perhaps, he could set out and reach his destination in the fall.

Of course he couldn’t. Exposure and long periods of starvation had turned him into a wraith. “It is a bad business having to go back to semi-civilization in such a shocking physical condition,” he scribbled in his diary with the last bit of his stubby pencil. “But it can’t be helped. I shall avoid the people I know as much as possible.”

He left his camp on June 21 and reached Resolution by July 10, so famished he could not put down solid food. For the rest of the day he slept under the Hudson’s Bay woodpile. He had survived a terrible winter but had accomplished nothing. As government surveyor Guy Blanchet said, “A normal man would not have got into such a situation but, if he did, neither could he have come through as Hornby did.”

Incredibly, in spite of all the trials he had faced, he planned to return to the east end of Great Slave for a

second

winter. He had learned little from his experience. He built another cabin not far from the site of the original one. He must have known by now what the winter held. It is hard to discover exactly what he planned to do; the record is clouded. Perhaps he didn’t know himself. He had written to George Douglas from Fort Resolution that he would like to spend a winter on the Thelon River at the very heart of the Barrens. That was wishful thinking. The winter that followed was a repeat of the one he had survived; he emerged once again emaciated and exhausted by the experience and with very little to show for it. For the moment, Hornby had had enough of the North. He went out to Edmonton, made a little money guiding for a group of big-time American game hunters, and drifted about until one day he met a man who would change his life. Or, more to the point, he met a man whose life would be changed nearly to the point of suicide by the year he spent with Hornby in the Barrens.

—TWO—

If you searched the country over, you would be hard put to find two characters who differed from each other as much as did James Critchell-Bullock and John Hornby. In matters of temperament, personality, outlook, and habit they were opposites. To confine the pair of them to a cave in the Barren Ground might be forecast as a folly, and a murderous one at that. Yet that would be their home for much of the winter of 1924–25. That they survived was largely because Hornby, ever the wanderer, was absent from the cave for days, even weeks, at a time.

They met, accidentally, at the King Edward Hotel on Front Street, Edmonton, in October 1923: two figures that fitted the images of “Mutt and Jeff,” a leading comic strip of the day. Hornby, at five foot four, was Jeff; Bullock, at six foot two, was Mutt (and twenty years younger than his new acquaintance). As they were both public school boys with appropriate accents, they fell into conversation. Bullock wrote to his brother that “for some unearthly reason [Hornby] … has taken a fancy to me.”

Bullock was an army man who had served as a subaltern with the Bengal Lancers in India and also with Allenby’s desert mounted corps in Palestine. Now he was an honorary captain, retired from the army after a bout of malaria. He was everything Hornby was not: fastidious, disciplined, punctual, well scrubbed, and well tailored. Before he quite realized it, Hornby had talked him into a vague scheme to study the Barren Ground, its flora and its fauna, and to trap white fox. He had no idea what he was getting into. Hornby, who was never one to downplay his own wilderness background, intrigued him and undoubtedly flattered him by offering him a partnership on such short acquaintance. He could be charming and open-hearted, as many who encountered him remarked. To Bullock, searching about in Edmonton for a new career in the Canadian North, he must have seemed the ideal companion and mentor.

In November 1923, Hornby, to test his companion’s stamina, took Bullock on a three-week excursion into the Rockies to gather specimens of mountain sheep and goats for the Edmonton Museum. That last purpose was abandoned as so many of Hornby’s plans were, but from his new partner’s viewpoint the trip was a success. He gained a boundless respect for Hornby, who packed the heaviest loads despite his small stature, showed less fatigue, and endured the bitter cold with only two blankets.

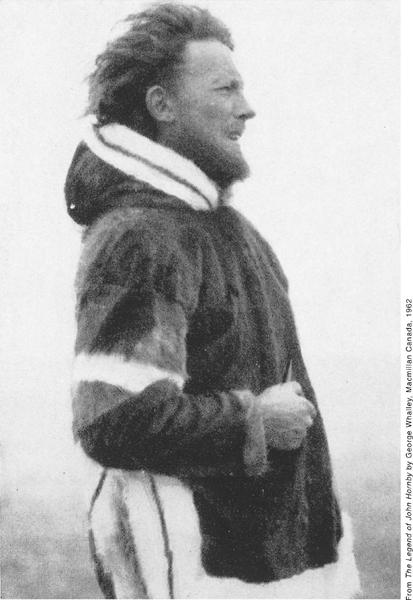

James Critchell-Bullock was first entranced, later disillusioned by Hornby

.

Their expedition to the Barrens was planned for the following summer. It would take three years and had two purposes. Bullock, who had been Allenby’s photographer in the Middle East, planned to make a motion picture of his Barren Ground experiences; Hornby hoped to get a government grant to study muskoxen and caribou. It would also be a business trip, one that Hornby claimed would bring them a gross profit of thirty thousand dollars in white fox furs. For a retired army man looking for some type of challenging enterprise in the colonies, it seemed attractive, even entrancing: a well-planned, well-ordered, and highly profitable venture with the added benefit of exploring an obscure but romantic corner of the country—and all in the company of an experienced and trusted guide. Bullock wrote to his brother that Hornby was held in high esteem “above everyone else in the whole North country,” but added, offhandedly, that “success only depends on getting him to be business-like.” That was like saying that success only depends on getting a one-legged man to run the hundred-yard dash.

In the interim, Hornby had befriended a vivacious Welsh woman, Olwen Newell, a recent arrival in Canada some twenty years his junior. It was his idea that she would go north with the expedition and write an account of his travels. She had responded with enthusiasm and soon found herself employed in the expedition’s office under Bullock, who was acting as a pro-tem business manager. It was obvious that she was attracted to Hornby, whom she found “a chivalrous man, fastidious in conversation and in his attitude to women … an unassuming man, conservative in dress.” A close friend warned her, however, that Hornby was not the marrying kind. Hornby saw her as “clever but a simple, affectionate and rather highly strung girl.”

He left early in February for Ottawa hoping to raise funds for his projected expedition, but there he met with a cool response. In his absence, Bullock concluded, wrongly, that Hornby and Olwen Newell were engaged and intended to marry. That would put an end to the expedition. He fired Miss Newell, and a flurry of letters and telegrams ensued between Hornby, Bullock, and Hornby’s friend Yardley Weaver, now an Edmonton lawyer. Hornby did his best to make it clear that he had no intention of marrying anyone. “I candidly told her, that I had never loved any girl,” Hornby told Weaver. “Besides I mentioned she was young & I am old.”