Prisoners of the North (26 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

There was a childlike aspect to Hornby’s character, which though it undoubtedly appealed to many who encountered him also created difficulties. He was not able to stick to any task for long. This was apparent in his relations with the newly arrived Oblate missionary Father Jean-Baptiste Rouvière, who was intent on establishing a mission to the Inuit of Coronation Gulf. Hornby established a firm friendship with Father Rouvière, with whom he whiled away many an hour over a chessboard. Hornby had attached himself to the mission, unofficially, and the two had started work on a small cabin on the north shore of Dease Lake (later renamed Lake Rouvière). Yet the job was scarcely underway when Hornby drifted off, leaving the priest to finish it himself over the following month. Where he went and why no one could tell, but in the coming years, his unexpected departures followed a pattern.

Hornby was easily bored and would lose interest in any project, abandoning it without any explanation, only to return later without a word. In this case there may have been a plausible reason for his actions. About this time he built another cabin for a young Sastudene Indian widow, Arimo, a charming and intelligent woman who was for a time his native “wife.” Hornby, if not in love, was certainly attached to her; she was one reason why he stayed so many months in the Dease Lake country.

By the spring of 1913 he had been five years in the North, out of touch with civilization. The events of the outside world—the death of Edward VII, the sinking of the

Titanic

—reached him long after the fact. His friends the Douglas brothers, George and Lionel, had departed, and a new priest, Father Guillaume LeRoux, had arrived, ostensibly to work under Father Rouvière in establishing the mission to the Inuit. LeRoux was a different creature from the easygoing and likeable Rouvière—hard-headed and hot-tempered, quick to flare up and confident enough to assume authority over the older priest, who was actually his senior. When LeRoux learned about Hornby’s dalliance with Arimo, he made his strong disapproval of the arrangement so clear that he managed to alienate her from Hornby.

With the priests occupying cabins at Hodgson’s Point, Hornby withdrew to his own domicile six miles away. It was not a happy winter, marked by a further quarrel between LeRoux and Hornby over a quantity of stores left behind by George Douglas for Hornby’s use, which LeRoux refused to let Hornby take from the storehouse.

Alone and lonely, Hornby, who had from time to time yearned for the solitary life, now found it oppressive. His disenchantment with the Great Bear country was beginning. On October 8, the two priests set off for the Coppermine, having learned that the time was ripe for establishing their mission on the northern coast. It was late in the season, and they were inexperienced travellers, badly provisioned and ill-clothed. Most of all, they had little understanding of the Inuit temperament.

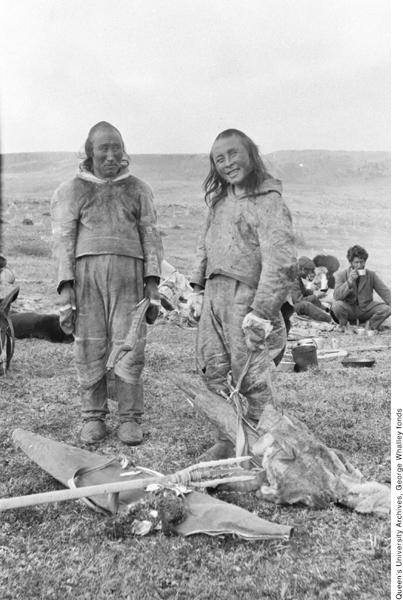

Arimo, Hornby’s one-time mistress, and her son Harry, on the Dease River, 1909

.

Hornby, who had had a run-in with two Inuit, apparently had told the priests before they left that the natives were “getting ugly.” It was a prescient warning. Neither priest was ever seen again, but their decomposed bodies were found in 1916 at Bloody Falls. The two Inuit who had earlier threatened Hornby, Sinnisiak, and Uluksuk, were eventually brought to trial for murder, found guilty, and given the death penalty. That was quickly commuted to life imprisonment, and with good reason, for these were Stone-Age people with a limited knowledge of the white man’s law. In the end they served two years of light detention in the Royal North West Mounted Police post at Fort Resolution and were then released to their own people.

None of this, of course, was known to Hornby, who had his own disaster to cope with in the fall of 1913. That October, he set off across the lake in the York boat

Jupiter

with an eclectic collection of Inuit artifacts he had put together during his years in the Dease country that he intended to present to the Edmonton Museum. It included a quantity of Inuit tools and clothes as well as a variety of specimens—flowers, bones, insects, and whatever furs and skins he had gathered. As he travelled down the lake a vicious gale blew up, buffeting the frail craft and throwing sheets of water into the boat, which was finally washed onto the shore and wrecked with the loss of most of its unique cargo.

It was perhaps the last straw. That winter Hornby decided to leave the North and, after nearly six years, venture into the Outside. He was a disillusioned man. The loneliness of his life, the loss of his precious specimens, and, most important, the tension between himself and the overbearing priest were all contributing factors. He was not the same man who had arrived at Great Bear Lake in 1908. The North had turned him into a creature who differed from those who had not experienced it as he had. Hornby was not one to plan his future, but it must have concerned him to realize that he was one of Service’s “men who don’t fit in.”

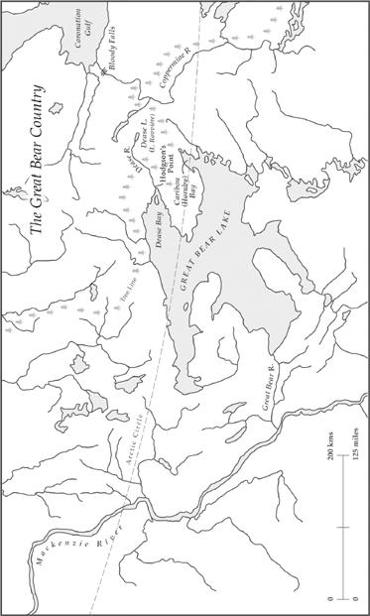

Inuit from Coronation Gulf with Hornby (background) on the edge of the Barrens

.

He had no plan for what he would do once he left the Great Bear Lake country. He spent a short time in Edmonton and went on to Lakefield, Ontario, where he was reunited with George Douglas. There and at Northcote, Douglas’s birthplace, the two friends had much to talk about, with Hornby relieving his frustrations.

At least he finally knew where his immediate future lay. World events made up his mind for him. The Great War had broken out; every able-bodied man was needed, and certainly Hornby, who thought nothing of packing 125 pounds on his back, was able. Douglas suggested he go to England, join the Imperial Army, and take a commission. Instead, in September 1914 Jack Hornby took the train to Valcartier, Quebec, and joined the 19th Alberta Dragoons.

However, as George Whalley has pointed out, “There can have been few men worse suited for army life than Hornby—by habit, temperament and desire.” The disciplined life of the parade ground and barrack room was as far from the free and easy vagabond existence as it was possible to get. Hornby didn’t look like a soldier, especially on leave. He turned up at the Royal Paddington Hotel in London to meet Douglas and was saved from rejection only by the timely interference of his friend. “He looked like a tramp—dirty trousers, a dirty pale blue silk shirt with pale yellow attached collar with ragged lace ribbon bands across the breast, and heavy moth-eaten astrakhan fur collar and cuffs.” Hornby was totally out of place, and Douglas steered this lost soul into the darkest corner of “a very gloomy dining room.”

Hornby’s unit embarked for France just in time to go into action in the second Battle of Ypres, notorious for Germany’s first use of poison gas. According to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel F. C. Jamieson, “Everybody liked him. He was cheerful and never complained” and was also willing to go out on patrols. Inwardly, however, he had no heart for the military life. “My thoughts are forever of the North,” he wrote to Douglas. “… I have lived too long with what here one calls the uncivilized races … to ever get accustomed to the continual wrangle & utter selfishness of the white races.…”

Douglas had written to tell him that no one had had any word of the two priests Rouvière and LeRoux. Hornby impulsively replied that he would try to get away and outfit a search expedition—a naive suggestion for a soldier in action at the front, especially one who had already applied for a commission. He was eventually gazetted as a second lieutenant in the South Lancashire regiment and must have seen considerable action, for he was mentioned in dispatches, then awarded the Military Cross for bravery, and wounded a month later. He told a friend that he did not expect to come out of the war alive and, as a result, was careless of danger.

Reports of his war service and subsequent activities are vague and confusing. A local newspaper near his hometown reported that he had been shot through the shoulder and was in hospital in London, which suggests his wounds were serious. But a fellow traveller who later crossed Great Slave Lake with him reported that “he had seven machine gun bullets through his body under his ribs and could get out of his sleeping bag only by hauling himself up by the tent pole.” Did he take convalescent leave from the hospital in London or did he just walk out, as Colonel Jamieson suggested? One thing is clear: though the war was still raging, he did not return to the trenches but took passage on a ship for Canada, ended up in Vancouver, and was posted Absent Without Leave.

The military authorities tried to track him down through George Douglas’s sister, but he proved elusive. He didn’t draw his pay and left no clue as to his whereabouts. Finally he turned up in Edmonton for a medical examination and was allowed to relinquish his commission on grounds of ill health caused by his wounds. He was granted the honorary rank of second lieutenant, an unusual reward for a flouting of army rules that might have led, had he gone AWL in action, to a firing squad.

The Great War affected many men, but the changes it wrought in Jack Hornby were deep and permanent. He was never quite the same man again. Flanders Fields were about as far from the limpid waters of Great Bear Lake as the moon itself. For half a dozen years Hornby had experienced the silence of the North, an eerie quiet broken only by the spectral laugh of the loon, the lonely howl of the wolf, and the whistle of the wind. In Flanders, his ears were assailed day and night by the cacophony of cannon and mortar, the chatter of machine guns, and, what was worse, the haunting cries of dying men. And there was more: the wretched trenches were filthy and sodden, the colourless landscape was pocked by shell holes and a confusion of mud and wire that bore no relation to the white world he had grown to love.

Mentally and emotionally, he was in bad shape. The noise of the guns, he told a friend in Edmonton, had driven him crazy. Worse, in his view, the army had turned him into a murderer. Civilization had gone mad. His only solution was to retreat again to the Far North; he was unfit for anything else, couldn’t work under others, and felt himself unable to take a job. “I wish I had never gone to the army nor had ever left the North,” he wrote to Douglas, who was working on an engineering job in Mexico. He asked at the same time for a loan of a hundred dollars. Douglas responded with a cheque.

“I’m going back home,” Hornby told the

Edmonton Bulletin

. “Along the Barren Lands and in the Arctic is my home.” Off he went, with only the money he had borrowed and very little equipment. The hotel keeper at Fort Smith described him as “this desperate man running away from civilization … making the tremendous trip in a little boat no better than a broken down packing case.” Hornby’s loathing of the civilized world and his obsession with the untrammelled North had reached the point where some who encountered him thought him out of his mind. His last gloomy winter on the big lake plus his war experiences had increased his eccentricities.

Hornby reached Dease Bay in September 1917, but it was not the hospitable place he had originally encountered. Once he had taken a proprietary interest in it; now it was “his” no longer. A new personality, Darcy Arden, a respected trader and prospector, had replaced him as the key figure among the Indians and had married Arimo, his one-time mistress. Hornby made his way across to Caribou Bay to the cabin he and Melvill had built, and here he crippled himself with an axe to the point where he could only crawl.