If These Walls Had Ears (9 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

In mid-October, there was an item in the

Arkansas Gazette

about one of President Roosevelt’s new programs, the Civilian Conservation Corps, generally referred to as the CCC. Hundreds

of boys would soon be shipped to Arkansas from places like California and Oregon. These young men were going to be put to

work building all sorts of public facilities, bridges, and dams. The plan, according to Guy Amsler, head of the State Parks

Commission, was to house some of the boys in barracks to be built at Fair Park, just a few blocks from Holly Street.

Charlie Armour had a degree in civil engineering. Maybe, he thought, these untrained crews needed just such a person to supervise

their work. It seemed to be a sign—especially since Guy Amsler, the Parks Commissioner, happened to be Charlie Armour’s neighbor

to the side, right across Lee Street.

He and Amsler talked, and yes, there were definite possibilities. One of the CCC projects was to be the construction of Boyle

Park, a 231-acre parcel of land southwest of the city. The Parks Commission was going to need a superintendent for Boyle.

Charlie Armour, Amsler said, had just the right qualifications.

So at age sixty-three, Charlie became a civil engineer again. His self reinventions had come full circle.

If there’s peace in your heart, your house will reflect it. If there’s rage, your house will reveal it. If there’s indecision

or indolence, your house will bear the brunt of it. In Jessie’s case, her new concern about her home showed itself in a feverish

rearrangement of the downstairs rooms. She moved the player piano from the living room to the front bedroom, which she was

now calling “the music room.” The middle bedroom was now “the sitting room.” Jessie had furnished it with a couple of easy

chairs, good lamps, and a lighted fish tank designed to provide a much-needed touch of serenity.

Of course, she probably attributed these moves to practical concerns. Radio had taken over the living room—by late 1933, Charles

and his father could sit by the fireplace and listen to “The Lone Ranger,” or Jessie and Jane could fill the wicker popper

and listen to “The Romance of Helen. Trent.” Now, suddenly, you needed a different place for reading and playing music. The

other factor was that the house was just so much larger with three fewer people in it. Grandma Jackson was dead, Grandmother

Armor had moved in with her other son in California, and Carolee had gotten married and was living in Boston. It seemed a

shame to let all that space go to waste.

Jessie’s brilliant idea no doubt resulted from just this sort of antsy preoccupation with the house. Not content to sit and

wait for events to overtake her family, she began to take stock of their strengths, their abilities, their holdings. The only

thing they had in excess, she decided, was space—the house itself. With so many people losing homes—or not able to afford

them in the first place—she suggested to Charlie that they start taking in boarders.

It was perfect: Jessie was, after all, schooled in the efficient running of a household. The going rate for room and board

was thirty dollars a month. Besides using the center to

hold

the center, they would be helping others who needed a place in these tough times. And one other thing in their favor: Arkansas

had passed a lenient divorce law, and people from all over the country were coming to the state to live during the three-month

residency requirement. This house, a family house, would be ideal for a young woman all alone and miles from home.

Jessie began advertising, and before long she had plenty of business. There was a lot of coming and going, but word of mouth

kept the house full most of the time. She and Charlie moved back downstairs, back to the middle bedroom. Charles moved to

the back bedroom, the one he had once shared with Grandma Jackson. Jane insisted on keeping her small bedroom at the top of

the stairs, but that still gave Jessie three rooms to rent. Mabel was back living in the room above the garage, so she could

help Jessie. And if she left again, they could rent out

her

room.

The first boarder was an old-maid schoolteacher named Miss Hairston. She taught first grade at Pulaski Heights Elementary,

just down the street, so she was delighted to find a homey place so close. She took the big upstairs room with the cedar closet,

the room separated from Jane’s by the pongee-covered French doors. Every night when Miss Hairston saw Jane’s light go out,

she would say the very same thing, never a variation. It drove Jane crazy.

“Good night, Janie dear,” she called out in her chirpy, schoolteachery voice.

“Good night, Miss Hairston,” Jane dutifully replied.

“Sleep tight, Janie dear.” With that, Jane pulled the covers over her head and burrowed in as deeply as she could.

It must’ve been strange at first, having other people in the house. I can’t imagine it myself—I feel a vague unease even when

our cleaning lady is here, no matter if she’s downstairs and I’m up in my office. But Jessie liked having new people to talk

with. She told them all about the neighbors, how they lived and what they did and who their people were. She talked about

her Sunday school class and tried to line up new members. She provided her boarders two meals a day, breakfast and supper.

At night, the boarders were welcome to come downstairs and sit by the fire or out on the porch. Charlie would tell them stories

about growing up on the farm in Kansas, or about the panthers in Louisiana.

Having boarders was almost like having parties again. A young lady from New York named Olive Hoeffleic came for a divorce,

bringing her mother with her. They waited out the three months eating Jessie’s good cooking, which had become more quintessentially

Southern than that of her Southern-born neighbors. Jessie didn’t cook Cajun-style, though, and one of the boarders was a young

woman from Louisiana, Jeanne Breaux, who missed her own mother’s cooking. Jeanne’s husband was a salesman whose territory

was Arkansas, and he wanted her in a family-type boardinghouse. The Armours could see why. Jeanne was as coquettish as they

come, and she immediately took over the social life of the house. In her Cajun accent, she led giggling conversations at the

dinner table. Her people were both French

and

Italian, and she would write to Tier mother, asking her to send recipes—red beans and rice, and all her other favorites—which

Jessie would then try. Jeanne would stand in the kitchen, translating while Jessie cooked, and everybody would be laughing

the whole time.

In 1935, Annabelle Ritter came. A Mississippian, she had moved to Little Rock in the late twenties to work in a branch office

of the General Motors Acceptance Corporation. She would become one of the Armours’ longest-running boarders, staying eight

years—longer than some of the future owners of this house.

It was as though the Armours and their boarders were an extended family. People came to Jessie looking for a home, and she

took them in. If they stayed long enough, they all got to know one another’s moods, quirks, nuances. Most of the boarders

could tell the Armours were having financial trouble, though the words were never actually spoken. Maybe it was just an occasional

look in Jessie’s or Charlie’s eye that gave it away. But it was no surprise, really, nor was it a stigma

—everybody

was having financial trouble to some degree.

One day in what must’ve been the fall of 1936, the Armours’ situation took a noticeable turn. Jessie announced to the boarders

that she was taking a job outside the house—she was going to be a dietician at the state mental hospital a few blocks away.

It was understandable. Charles and Jane were now in college, and two children in college at the same time would be hard for

any family. Of course, the boarders wondered what this meant for them. No, Jessie said, she wasn’t closing the boardinghouse;

she was just taking on additional work.

She still cooked breakfast for everyone in the morning before going off to her other job. In the afternoons, she would come

home with jars of food left over from the meals she had prepared for the patients. These leftovers would often be the evening

meal for the residents of 501 Holly.

Then, in early 1937, Jessie called Annabelle Ritter aside and told her she had some bad news. The Armours were going to have

to move. The present arrangement just wasn’t working. They were keeping the house, however, and Jessie had arranged for a

family called the Kemps to rent it and to allow the boarders to stay. Unfortunately, they would no longer be boarders; they

would just be renters—but they would be welcome to keep their own food in the refrigerator and prepare it themselves.

Annabelle was astounded, but Jessie waved aside any show of pity. They would be fine. They had taken an apartment farther

into the Heights, she said, over on North Tyler Street. It was a nice apartment—a duplex, actually. Charles and Jane were

going to drop out of college and get jobs until the family got back on its feet.

What Jessie didn’t tell Annabelle that day was that Charlie had already declared bankruptcy. They had held on for a long time,

but the odds were stacked too high against them. Charlie had gone to court the previous summer, in August of 1936. He had

been sixty-six years old at the time. The paperwork on the bankruptcy was surprisingly brief. “In the matter of C. W. L. Armour,

Bkcy. No. 4499,” it began. “At Little Rock, on the 31st day of August, A.D. 1936, before the Honorable John E. Martineau .

. .” Though it was written in legalese, certain phrases stood out as brutally to the point: “. . . having been heard and duly

considered, the said C. W. L. Armour is hereby declared and adjudged a bankrupt. . .”

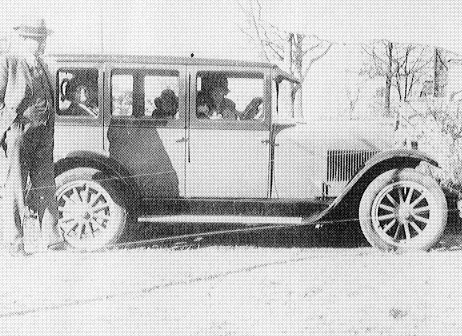

When moving day came, Jessie had packed their clothes and a few pieces of furniture. After checking the house one last time,

she closed the door and got into the car, where Charlie was waiting. In my mind’s eye, I see them driving off, bravely, without

looking back.

The writer Mark Twain lived for many years in a flamboyant Stick Style house in Hartford, Connecticut. It was there that he

wrote some of his most famous books—The

Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s

Court.

For Twain and his wife, Livy, the years in that house were the best of their lives. “To us,” Twain wrote, “our house was

not unsentient matter—it had a heart, and a soul, and eyes to see us with; and approvals and solicitudes and deep sympathies;

it was of us, and we were in its confidence, and lived in its grace and in the peace of its benediction. We never came home

from an absence that its face did not light up and speak out its eloquent welcome—and we could not enter it unmoved.”

Those lines inevitably come to me when I think of the Armours driving away from their house on Holly Street. They had lost

its approvals, its confidence, the peace of its benediction. Without those things, they were unsheltered in a way that’s ultimately

more damaging than simply not having that roof over their heads. Especially Charlie. His heart and soul were now open to the

elements.

The Armours tried to hold the center, but finally they had to 501 Holly

Armour

1937

1947

1947E

very weekday morning, I drive my stepdaughter Bret to school. Though Bret would tell you there are some days when I’m the

grumpiest of chauffeurs, I nevertheless enjoy these moments—they’re a comforting ritual, and no doubt part of the reason I

feel at home at 501 Holly. My own two sons have lived in a different state from me since David was seven—they moved on his

seventh birthday, actually—and Matthew was seven months. Herding eleven-year-old Bret and our miniature schnauzer, Snapp,

into the car every morning, I feel, when I think about it, that I’ve managed to double back and recapture a piece of something

I had lost.

The subject of loss often crosses my mind on the way to school. That’s because, following Kavanaugh Street (called Prospect

until the mid-thirties) farther into the Heights, I pass right by North Tyler Street, where Charlie and Jessie and Charles

and Jane moved when they had to leave the house on Holly. The duplex they lived in is the second one from the corner, and

I give it a respectful glance every day as I drive by.