If These Walls Had Ears (12 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

Charles had decided to go back to the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville to finish up and get his law degree. Millie was

thinking of getting a graduate degree in nursing. They had their sights set on the spring semester of 1947. Jane and Pem had

big plans, too. They were planning to buy a house, but they weren’t going to put

all

their money down, because Pem wanted to start his own radio-repair business.

During that fall of 1946, Jessie worked with Millie to get ready for the baby. They embroidered sixteen little receiving blankets,

and they had a whole layette fixed. They enjoyed doing that together. It was a good time in the house, the first truly hopeful

time in almost twenty years. On the other hand, in a matter of months all the children would be gone and Jessie would be left

there by herself. She was almost sixty years old. It was too much house for one person, and boarders weren’t an answer anymore.

It was postwar—people were going to college, having children, buying houses of their own. Besides, Jessie didn’t need the

money now. Uncle Ben had died and left everything to her. Why stay here? Why not take an apartment at the state hospital and

sell this place? She might even travel a bit—might finally get to visit some of those exotic spots in the world that Charlie,

with his kindred adventurous spirit, had hoped to see but never had.

One night at dinner, Jessie brought up the subject: Despite the pain that these walls had known, this house had been good

to her, to

all

of them. They had made many memories here—the music and the dancing and the slow, cradling arc of the porch swing on summer

nights—but those memories were theirs forever, no matter where they might live. Maybe, after nearly twenty-four years, more

than a generation, it was time to move on.

I have a photograph, probably taken their last fall at 501 Holly. Jessie and Charles and some of their neighbors are gathered

around the front steps just feet from where the Nu Grape car and the spindly elm were in that photo from two decades past.

Charles is telling a story, and everyone is laughing.

But I see another snapshot within that one: Charles is frail and balding, and Jessie is an old woman with white hair and the

stiff stance of age. In the upper right-hand corner, mature tree leaves rustle near the house, casting shadows.

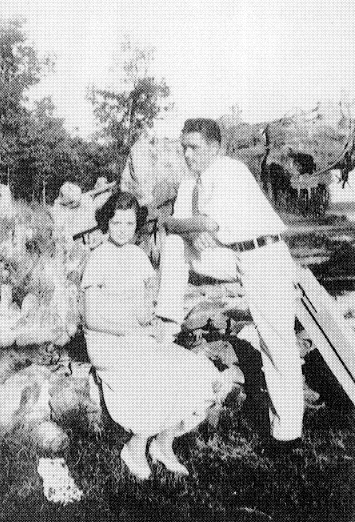

Ruth Talyor and Billie Lee Murphree courting in the 1930s.

Murphree

1947

1948

1948T

hese words are being written in mid-March, which means spring in Arkansas. The French doors to my upstairs office are open.

The baby leaves on the elm tree are backlit by the sun, rendering them a translucent yellow-green. Golden jonquils sway in

the yard.

The older I get, the more I appreciate spring. The other day I sat on the steps outside the kitchen, eating a bowl of cereal.

I watched a cardinal hopping in the hedge. I noticed the shoots of new lariope pushing through the ground. I saw a squirrel

sail from the upper branches of the walnut tree, which already has buds popping, to the maple, which doesn’t. Used to be,

spring meant I could play golf or run on real ground instead of a treadmill. Now I welcome spring from a deeper part of me.

To a homeowner, though, spring is like the aftermath of an accident: You’ve apparently

survived,

but you have to check yourself all over to see if your parts are still in working order. I took my coffee out into the yard

and inspected the house. A board has bowed away from an upstairs window. A little more paint seems to have flaked off from

the eaves. The part of the porch roof that was rebuilt two years ago already looks a tad warped, and more nails are pushing

up through the tar paper on top. The required physical therapy includes serious splints and skin grafts, most of which I won’t

find the time or the money to do right away. Instead, I’ll worry about it while attending to the relatively simple acts of

regrooming, like a man who needs a heart bypass but gets a haircut instead.

Inside, Beth prunes the girls’ closets, while I tend to the bushes that clothe the house. We buy herbs, and in time we’ll

plant a host of impatiens, the only flower that blooms with any consistency in the shady back garden. I carry plants from

their inside winter quarters back out to the open-air porch. I round up dead leaves from the driveway and patio. Sometimes,

when I want to stretch the job and dream, I use the big new push broom Beth bought me. Other times, I go to the trouble of

hauling out the orange electric cords and cranking up my noisy leaf blower—the one half-covered in dried tar from when my

stack of paint cans and roof tar caved in and spilled last summer in the darkness of the shed when I was away on vacation.

There’s something disconcerting about a tar-encrusted electric yard tool. I remind myself more and more of my father.

Ivy patrol is one of my spring rituals. Ivy and houses, both con artists, have joined forces in a fascinating collusion. Ivy

on a house speaks to us in soothing terms of permanence, stability, stateliness, even money. The truth is, ivy is nothing

but death in a green suit. When growing on a brick or stucco wall, ivy will leech out the mortar and fester the skin. Last

year, I spent a day ripping the ivy away from the north side of the house. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t remove some

of the pieces of the vine itself, short sections marked with tiny cross-hatchings from which leaves used to grow. They’re

still there, looking like sutured slashes. The people who painted this house last time simply coated over old ivy scars, incorporating

marks of past mortal encounters into the building’s newest face.

Spring always surprises me by revealing a kind of amnesia on my part. I guess it’s a self-protective forgetting, a way to

forge ahead blindly instead of being debilitated by focusing on all the things that are wrong with this life—or, more specifically,

this house. For example, during the winter I inevitably forget how absurdly slanted the back patio is. It’s true that the

ground itself slopes from north to south, but you’d think that whoever built this brick patio would’ve considered the genial

rite of balancing a gin and tonic on a table rather than simply going with nature’s flow. Actually, I now know who constructed

this patio, a story I’ll tell in due time. Knowing who built it only amazes me more.

In spring, I inevitably think how nice it would be to open all the windows and catch some of that cross ventilation old Charlie

Armour so cunningly cultivated. Then I recall that the windows are painted shut. Downstairs, the windows are still sealed.

Upstairs, we’ve spent thousands of dollars refurbishing the casement windows and screens so we can open the house to the breezes

of spring. Casement windows require a cranking tool, however, and all of the original window-opening tools were lost. We had

one of the workmen make a couple of ersatz tools, and now we know why we couldn’t find the originals—half the time, we can’t

even find the new ones. “Have you seen the thing?” is a question that will forever mean spring to me.

Spring is also the season when I curse poor old Charlie Armour just a little bit. Surprisingly, it’s because of the front

porch, that charmer that has seduced so many starry-eyed buyers, including me. The porch makes an L, the short end jutting

a few feet along the side of the house, the long part stretching across the front. And yet the porch roof only goes three-fourths

of the way across the front of the house. This means that I pull my car into the driveway and, if it’s raining, I step out

and walk ten feet or so uncovered. What was the sense in that? Why on earth, if you were going to have a porch at all, wouldn’t

you cover it all the way over to where you park your car?

I usually ponder this as I scrub that unprotected portion of the porch in spring. All winter long, that section has been exposed

to the elements, which, in one cracked spot particularly, have built up layer by layer into a nasty deposit of sediment. But

here’s where my annual amnesia comes in. It’s while I’m scrubbing the porch that I’m reminded of the seasons

within

the season. Beginning in spring, the elm tree that hovers above the open part of the porch is always dropping something.

First, there’s the joyous bud season, followed closely by an intense week of what can only be called spring bird-shit season,

followed by the delicate baby-leaf season, followed by some kind of translucent-spore season, which coincides with pollen

season, whose hallmark is a coat of green dust over cars, rocking chairs, and, certainly, the unexposed part of the porch.

Then comes summer, with the elm’s glorious leafy shade. I’m convinced that that elm tree saves us hundreds of dollars every

year in air-conditioning costs. In summer, the branches are full of chirping, singing birds, which are wonderful to listen

to on the front porch. They don’t announce their presence as insistently as before, but it’s still inadvisable for me to own

a convertible. Then fall comes, producing some kind of seed that results in

fall

bird-shit season. Then the leaves dry up. Finally, they die and float gently to the ground.

I guess it’s just life. Maybe Charlie Armour left part of the porch uncovered to remind himself that a house can’t protect

you all the time.

Spring is an appropriate season to be thinking about the Murphrees moving to Holly Street. There’s a rhythm to life itself,

an ebb, a flow. After a quarter century, the Armours’ time here was spent. But as Jessie, old and tired, was coming to that

decision, seven blocks away a woman half her age named Ruth Murphree was complaining to her husband, Billie, that they had

to have more space. Their conversation wasn’t warm or wistful. Ruth was angry and had been for years. Billie had been away

in the navy since 1942. When the war was over, his discharge had been frozen for reasons Ruth couldn’t fathom. They didn’t

release him until February 1946. By then, everybody was home, the good jobs taken. But the main complaint was that while Billie

had been stuck in the South Pacific on a mail ship, Ruth had been cooped up in a tiny house on Pine Street with two preschool

daughters

plus

Billie’s recently widowed mother and

her

nine-year-old son, whom. Ruth referred to as a “menopause baby,”

plus

having to work as secretary to U.S. congressman Brooks Hays. No, Ruth hadn’t been charmed by this arrangement. “The next

war we have,” she told her husband, “I’ll go and you’ll stay home.”

Once Billie got a taste of what Ruth had been putting up with, it didn’t take him long to say to her, “Go find us a bigger

house.” They preferred to stay in Hillcrest. One morning, she saw an advertisement for a house at 501 Holly. It had five or

six bedrooms, depending on your needs. Ruth thought that sounded heavenly. She called the Realtor and arranged a viewing.

It was love at first sight. She was enchanted by the front porch, the beautiful hardwood floors, the music room, the overwhelming

spaciousness

of the place.

She took Billie back that very afternoon. He was impressed, too. Besides, if it pleased Ruth, that was saying a lot. In the

decade they had been married, he had found that she wasn’t easy to satisfy. They bought it without quibbling, paying Jessica

J. Armour $13,500 in cash for the right to play out their own dreams of home.

The Murphrees lived in this house during a seasonal change in the country, too. It began as a kind of springtime, a postwar

blush of budding promise, though it didn’t end that way. I remember the beginning of that time as a brief moment when it was

possible to believe in goodness and mercy and safety and peace—to

assume

those things. That was in the period from the late 1940s until the mid-1950s. I was a child then, age five to about eleven,

and I’m sure that was a good part of it, the illusions of childhood. But the times seemed to foster illusions—maybe even to

depend on them. I know now that my parents dealt in those years with the timeless trials of adulthood, but even they appeared

to cling to the idea of something approaching innocence.

For me, those were days of roaming loose through my neighborhood, of playing army and cowboys and, occasionally, doctor under

the house with neighbor girls. They were days of comic books and baseball cards and bike riding with no hands. There were

heroes like Mickey Mantle and Eddie Mathews and Roy Rogers and Lash La Rue. There were fears of the requisite neighborhood

bully, in my case a strange bird called “Booger Red,” who leapt out of trees onto people. There was a first bite of a new

dish called “pizza pie,” and a sip of my dad’s Schlitz, a taste that lives in my memory and still defines beer for me. There

were after-church dinners of fried chicken with rice and gravy. There were lightning bugs, and games of kick the can until

dark, when you heard your mother calling you for supper and you reluctantly parted from your friends for the night and trudged

in the blue dusk toward the lights of home.