If These Walls Had Ears (4 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

The first picture I ever saw of

any

of this house’s past lives was sent to me by Ruth Chapin, who had grown up across the street. It was actually a photocopy

of a snapshot, dated “1927 or ’28,” and it was gray and grainy, like memory itself.

In the foreground are two young women, identified as Ruth Ream—at that time—and Clara Young, who lived in the house next door

to 501. It’s a snowy day, and Ruth is holding what looks like a black-and-white dog. I can see Clara’s house in the background

and, next to it, the unmistakable shape of the one I’ve come to know. But there are disturbing differences. There’s a nakedness

to my house. Then 1 realize the massive elm tree by the driveway seems to be missing. No: Resorting to a magnifying glass,

I can just make out a thin vertical line that looks, comparing it to the house, to be about ten or fifteen feet tall, and

skinny.

Then I look up from my desk and out through the front French doors upstairs. Broad limbs, heavy with age, stretch up and out,

their span not even contained within the double window frame. Three years ago, I even had to have that tree cabled together

at the Y to keep it from splitting from its weight. I look back at the grainy picture. It’s hard to reconcile the two images.

Photographs are tricky, and I’ve come to believe that most of us don’t really see what’s in them. More than once over the

past year, I’ve studied faces and bodies in a picture snapped in this yard, and then I’ve stepped outside to look at the very

spot where it was taken half a century, or more, before. No one is there, of course. I pore over the backgrounds to see if

I can pick up an echo.

Over time, though, I’ve become able to summon up the figures and faces, and I realize now that this process is one of the

great benefits of this quest of mine. One of the major characters in this saga is time. Most of us see the world only the

way it is as we’re looking at it. We take a snapshot of that moment and believe we’ve captured something. But time, that invisible

trickster, is the real subject of every photograph. Every item in every snapshot is shaped, or colored—or faded—by time in

one of its permutations. A brilliant writer named Robert Grudin has called time “the fourth dimension,” and I’ve become increasingly

able to see this house in that way: height, width, depth, time. When I first moved into 501 Holly, the rooms looked empty.

Now I live with ghosts.

One of them drove the car parked in front of the house in that grainy snapshot Ruth sent me. That it’s not a normal car is

apparent even without the magnifying glass. It

looks

like an old wooden barrel on wheels, with a flimsy canvas top. I’ve since learned that it was an automobile built in the

shape of a Nu Grape soda pop bottle, that it was painted purple, and that the radiator (which I can’t see in this picture)

was made to look like a bottle cap.

The man who created that car was named Charles Webster Leverton Armour, known to his wife, Jessica, as Charlie. Charlie and

Jessie, as he called

her,

had met in the still-frontierish town of Fort Smith, Arkansas, sometime around 1908. Jessie Jackson, then age twenty-one,

was a bright, outgoing, self-confident young woman from St. Paul, Minnesota. A graduate dietician, as successful home ec majors

were known in those days, she had sent letters to schools all over the country announcing her qualifications and her willingness

to relocate. She was a woman ahead of her time. One day, Jessie heard from the principal of the high school in Fort Smith.

He wondered if she would come establish a “domestic science” program at his school. It was just the kind of adventure Jessie

was looking for. She packed up her best friend and took her along, too.

Jessie Armours with her children, fane and Charles.

Jessie’s best friend also happened to be her mother. Cynthia Jane Paxton Jackson had been widowed when Jessie was three, and

the two of them had gone to live with Cynthia’s brother, Ben Paxton, a bachelor doctor and world traveler. Jessie’s father,

William Malcolm Jackson, had also been a doctor. Back in those days, doctors made house calls—even out to the country in the

middle of a Minnesota winter. After one such visit, Dr. Jackson caught pneumonia and died. Cynthia never remarried.

The above story was told to me one crisp blue day in the fall of 1992. I had driven out to the Scott community northeast of

town to see Jane Armour McRae, then seventy-six, the only surviving child of Jessie and Charlie Armour. Jane is a tall woman,

angular, and on the day of that first meeting I noted that she was wearing heavy blue eye shadow and a rinse on her hair the

approximate color of Windex. She laughed heartily and often. On a later visit, the color was less vibrant, but her attitude

was the same: When she looks at you, you get the feeling there’s a party going on behind her eyes.

Her mother, Jane said, had two great loves: talking and dancing. In Fort Smith, she met a man who shared both of those passions.

A garrulous real estate salesman from Kansas, Charlie was seventeen years older than Jessie, and he had a past. For one thing,

this was his second career. He had studied civil engineering at the University of Kansas and had spent several years surveying

for a railroad down in Louisiana. He was brimming with tales about that exotic land, which was about as different from his

own home state as any place could possibly be. He mesmerized Jessie with stories of wildcats and things up in trees that would

howl in the night. He could still make the sound of a panther. He had loved Louisiana, had been taken with its food, its eccentricities,

its attitude. He had adopted those Southern ways with the passion of one who happens upon a new part of the world and discovers

himself in it. To Jessie Jackson, who had lived her entire life in the North, this smooth-talking fellow seemed the epitome

of Southern charm, especially with his three first names. Up where Jessica came from, they’re more frugal with their appellations.

He had also been married once, and had a young daughter, a toddler, Caroline, called Carolee, who lived with him. He was a

widower, he said. He and his daughter lived in an imposing Queen Anne mansion on a hill outside of town. It was the kind of

estate that had a name—Lone Pine, which referred to a massive old tree that towered over the house and stood out in solitary

splendor against the sky. There was a story about that house. Even if Charlie hadn’t told Jessica about it, she would’ve heard.

It was the sort of story that people would whisper behind their hands whenever Charlie walked into a room.

His first wife had killed herself at Lone Pine. One day Charlie and his daughter were walking out in the large yard when Charlie

heard a shot. He swept Carolee into his arms and ran back to the house. When they got to the front steps, they saw her—his

wife, and Carolee’s mother—sprawled dead on the porch, a pistol in her hand. If Charlie had any idea why she did it, he never

said. All his family ever knew was that his first wife was “nervously unbalanced” and took her own life.

Jessie and Charlie were both big people, tending toward heaviness, he standing five foot nine or ten, and Jessie five six

or seven. They had big spirits, too. Each threatened to outtalk the other. Charlie teased Jessie

and

her mother, and both women were smitten by him. In 1912, when forty-two-year-old Charlie asked Jessie to marry him, she responded

with an unqualified yes. She and her mother moved into the big house on the hill, and for several years they lived there together,

a blended family—rare in those days. Charlie pursued his real estate business and Jessie taught school. Cynthia Jane, now

known as Grandma Jackson, spent her days taking care of Carolee, this instant grandchild who had washed into her life by fate.

Carolee was six at the time of the marriage.

In 1914, Jessie gave birth to her first child, a son. All four of his father’s names were bestowed upon him, and he went by

Charles. Two years later, a daughter was born. She was named Jane, after Jessie’s mother.

* * *

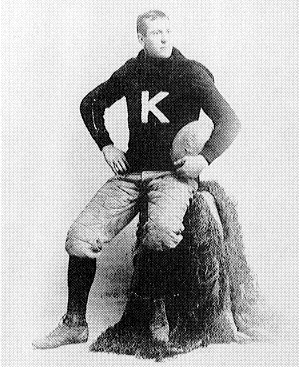

Charlie Armour as a young grid star in Kansas. His son, Charles, would always feel that he never quite measured up in his father’s eyes.

In time, through research, I would come to know things about her parents that even Jane didn’t know. Still, I worried that

they were eluding me. It’s impossible to get inside another person’s heart, even if you live together. But these were people

I had never met, people who had lived in a completely different age. I stared at photographs and read stories into them.

Jessie displays a face straight from a Grecian urn—strong chin, prominent nose, high forehead, with a tousle of thick dark

curls. Her eyes are intelligent, hawklike,

ready.

I imagine her dancing, whirling. I imagine her as a fiercely protective mother.

As for Charlie, I can’t see much at all in his pictures. In every one, from his college days as a football player to his middle

years as head of a household, the camera doesn’t catch his spark. With some people, it does. He had a face like Kansas—wide,

open, no sharp angles. With him, the rest of his family will be smiling, but he stands there expressionless. It’s not anger,

not pomposity, not shyness. It’s just

nothing:

no hint of the salesman with the gift of gab:, no glimpse of the music lover undaunted by a dance floor; no sign of the searching

heart that would cause this man to reinvent himself time and time again.

Charlie scares me. He strikes me as a man who was forever chasing something but never quite held it securely in his hands.

Jessie and Charlie were married for eleven years before they built the house on Holly Street. In that time, they had lived

in four other houses in three other towns. They left Fort Smith in 1918 because Charlie was offered the chance to manage a

cotton plantation in Elaine, Arkansas. They left Elaine after a race riot erupted and many people were killed. They next moved

to Memphis, where they lived in a big two-story rented house and Charlie went back into real estate. They moved from that

house to a smaller one when, in 1921, Charlie’s head was turned by the discovery of oil in south Arkansas. He just

had

to try his luck in the oil fields, but there’s no evidence that he had any luck—not the kind that would’ve

changed

his luck. He was fifty-one and still struggling.

While he was gone, Jessie made sure the family was well clothed and well fed. She sewed their outfits, cooked their meals.

Carolee was a teenager by this time, and the smaller children were both in school. Young Charles may’ve been glad to have

some time away from his father. Charles was a worrier, and lie wasn’t particularly athletic. Many years later, he would confess

that he never felt he measured up in his father’s eyes.

In the spring of 1923, the Armours packed themselves into their Overland touring car and headed west from Memphis toward the

site of Charlie’s latest incarnation. It was to take place in Little Rock, Arkansas. The family was moving so Charlie could

try his hand in the hot new industry of soda-pop bottling.

It looked like a sure bet for the times—especially now with Prohibition, when people couldn’t openly slake their thirst with

beer. More than that, though, bottled soft drinks seemed a perfect response to the whimsy, the mobility, and the pleasure

seeking of the 1920s. I can imagine Charlie bursting with anticipation. This was totally different from anything he had ever

done, and yet it was right up his alley. He was a people person, and this was a people business. He had lots of ideas that

he wanted to try. Everybody knew that men all over the country had gotten filthy rich owning Coca-Cola bottling plants. This

wasn’t going to be that, exactly—Charlie was becoming a partner in something called Arkola, which had started in 1920 to take

advantage of the cola craze. The company also bottled ginger ale and root beer. But the big reason Charlie was so excited

was that the company had just landed the contract for Nu Grape, and this was going to be Charlie’s baby.

It didn’t take the Armours long to find out that the most desirable neighborhood in Little Rock was a western suburb called

Pulaski Heights. By this time, the Heights had become annexed to Little Rock. Charlie and Jessie took the family on a spin

through the hilly, winding streets. The old trees—oaks and elms and walnuts and pines—formed canopies over the paved roadways.

By now, there were different neighborhoods within the Heights itself, and commercial areas had sprung up at different points

along the streetcar line. The area where Auten and Moss had built their homes was now called Hillcrest, and its commercial

district included a beautiful two-story Spanish Gothic building that encompassed the town hall, the civic center, and five

storefronts facing Prospect Avenue. Across the street was a fire station. The Heights was home to Little Rock College, to

a Catholic girls’ school called Mount St. Mary’s, and to several elementary and junior high schools.