If These Walls Had Ears (24 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

I refrained from saying that he wasn’t telling

me

anything new. I guess I could afford to be magnanimous. Then, as now, I hadn’t discovered a hidden disaster the way some

past owners had—starting with Ed and Sheri Kramer.

Before Ed Kramer moves into a house, he gets the dimensions of its rooms, and he draws them out on paper. Then he pencils

in the furniture, erasing and resketching until he gets the placement just right.

He pooh-poohs any deeper reading of this, saying that it’s simply a smart way to handle what otherwise would be a pressured

task. “It keeps us from having to decide while the movers stand around waiting,” he says.

But I think there’s more to it than that. When I was twelve and living in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, I persuaded my parents

to buy me my first pair of loafers—cool shoes, as compared with whatever lace-ups I had been wearing. The local department

store didn’t have my size, so they had to order the shoes. I thought I couldn’t

stand

it until those loafers—my new persona—arrived, and every day in Mrs. Smith’s sixth-grade class, I drew pictures of the shoes

in the margins of my notebook.

Ed is a man who would understand that. He feels deeply about his surroundings, and he attributes that to having seen the worst

fears of childhood come true—he lost both his parents early and found himself in a way dispossessed. Heirlooms and mementos

and items of personal expression take on special meaning for him. They add up to

home.

“I love the enclosures that I’m in,” he says. “I adapt them to myself, and try to make them resonate with me.”

He and Sheri generally agree on decor, Ed says, and I don’t doubt it: I sense that Sheri has enough strength to be sensitive

to his greater need to make rooms his own and that she allows Ed to impress her continually with his talent, his imagination,

his wit. For example, when he lived in New York, he built a “piano bar,” a visual pun—a bar made from the top of a piano.

At Holly Street, he sketched that into the place of honor in the dining room—the east wall, the one you see straight ahead

when you walk through the front door. Above the piano bar, he drew in a nice mirror. To separate the living room from the

dining room, he penciled in their champagne-colored sofa, with the shapely legged heirloom table at the end by the wall. Across

the room, near his precious stereo equipment, he drew in the armchair from his mother.

He took special care sketching in the room that was to be his study. In the bay window, he pictured his massive sawhorse-anddoor-top

desk, with his typewriter in the center. He envisioned himself working facing the window, his back to the room—to the wall-to-wall

bookcase holding his beloved books, to the sprawling beanbag chair that Sheri had made just for him, to the urn of dried flowers

she had lovingly placed in the corner by the door.

When they finally moved in in the spring of 1973, Sheri painted Ed’s study a deep and moody blue. It’s a color he loves. He

remembers one night being in his wonderful new study all alone, unpacking his books, and suddenly he couldn’t believe that

all this space was just for him. “The sense of space made me giddy,” he says. “There was so much space that I would get

lonesome,

and I would have to go upstairs where Sheri was unpacking in another room.”

Soon after that, he took his seat at his desk and rolled a piece of paper into his typewriter. He placed his fine, gently

curving pipe to his lips and fired it up. Sheri says she hardly saw him again the three years they lived here.

During the days, Ed would be at the Arts Center, working with the theater group. At night, after supper—and on evenings when

some of the cast didn’t come over to plan or rehearse behind closed doors in Ed’s study—he would repair to his room and work

on a screenplay he was calling

Sweet William,

about a countrified criminal investigator who found himself teamed up on a bizarre case with a hypochondriacal medical examiner.

Ed would sit there at his typewriter, dreaming about another world, tapping late into the night.

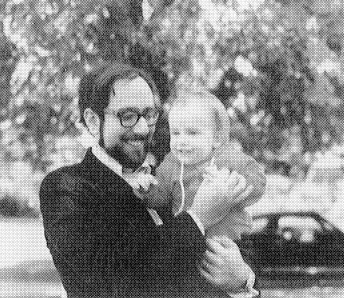

Ed and Siggy in the front yard, four months after they moved in

.

Whenever he needed inspiration, day or night, he would step outside into his yard and walk among the trees, smoking his pipe

and absorbing the miraculous strength of this house and land he now owned. He couldn’t believe his good fortune. I have a

photograph of Ed and Siggy in the front yard of 501 Holly in the fall of 1973. It’s one of those sun-dappled days—not just

in the neighborhood, but in Ed Kramer’s young life. He would’ve been twenty-six in this picture, and Sig would’ve been just

over a year old. They had been in this house for only four months. On the September day this photo was snapped, Sheri was

two months away from giving birth to their sec ond child. It’s a moment out of time. Far away from this halcyon spot, the

President of the United States was being assailed for sins against the people who had sent him to office. But here in the

middle of the country, on this insignificant plot of land, there was still hope in the lasting virtues of home and family.

“To think,” Ed says, still amazed, “that I could, at that age, presume to have a house like that, in that neighborhood.” He

counted the trees, and he would say, over and over to make it sink in, “These are my trees. These are

my

trees.” He felt a kinship with each and every one of them. He particularly loved the tulip poplar, which, people had told

him, had been designated the number-one tree of its kind in all of Arkansas. It grew straight and tall, towering over the

house. It was taller by far than the other trees—the big elm, the maple, the walnut in the side yard, any of them. The tulip

tree stood in the front on the edge of the hill, and twice a year it stunned passersby with the beauty of its blossoms.

To a boy from Brooklyn, a tree was a precious thing. This one was simply magnificent.

Rita Grimes visited often in the early days. Sheri still recalls the time Rita and Mark arrived on the front porch, and Mark,

who tried to open the front door but found it locked, threw a tantrum screaming and kicking the door, still not quite grasping

that this house he had lived in for so long was no longer his.

At first, Rita enjoyed being back on Holly Street. But it wasn’t long before she noticed a change in Sheri’s attitude. Sheri

herself admits to having a temper, and Rita says Sheri never had any trouble expressing her opinion. That’s what began happening

during Rita’s visits. Before the Kramers had bought the house, Sheri had asked Rita what their real estate taxes were. Rita

had given her a number, but now the property had been reassessed and taxes had been increased. Sheri was upset, and she let

Rita know it. She began mentioning the taxes every time Rita came over. “She thought we had pulled a fast one on her,” Rita

says. After a few such visits, Rita stopped going—the situation was just too uncomfortable. Rita says Sheri never once called

to see why she’d stopped coming to see her.

Sheri doesn’t remember the tax problem, but she does recall an incident about a year after they had lived in the house. Sheri

and Ed were at a department store, and suddenly who ambles over to say hello but Roy Grimes. Ed was livid. “Come on,” he said

to his wife, “I’m not waiting. Let’s get out of here.” And with that, he stomped away, Sheri following behind.

The anger festering in Ed Kramer had begun with the discovery that the wall and part of the floor of the downstairs bathroom

were rotten and would need to be replaced, along with the walls in the back bedroom. “We had a termite inspector go under

the house,” Ed recalls. “The guy said, ‘Right under this bathroom, all this wood is just bad wood. It’s going to have to come

out.’ He told us of various sites on the underframing of the house that looked very bad.”

Even now, Ed is adamant in his belief that the Grimeses weren’t fully forthcoming during the sale of 501 Holly. Ed admits

that he and Sheri were infatuated with the house and so overlooked certain problems—Sheri recalls that the floor seemed to

sag between the living room and the former music room, and there were cracks in the plaster, especially going up the stairwell

wall. Of course, the trouble in the downstairs back bedroom was obvious, even to buyers blinded by the

worst

case of house fever: The window frames were literally falling out of the wall, Sheri recalls, though no air seemed to be

coming in. That room was so bad that, after they bought the house, Ed and Sheri simply shut the door and never went in there.

It became a storage room.

“Yes, we saw things that needed to be done,” says Ed, “but they were just the tip of the iceberg. When we moved in, we set

priorities—we’ll fix this but we won’t worry about that now. We figured it was a lifelong process. I like to live in a house

awhile before I go about changing it. You don’t know in what way you want to alter the house, or alter yourself to the house.

You want to give the house a chance to represent itself.

“Then we came to find out there was all this extensive work that was going to need to be done. It absolutely devastated us

financially. It stripped our resources entirely.”

So that when Ed looked up in the department store and saw a smiling Roy Grimes walking toward him, all the rage that had been

bubbling up in him overflowed. “I was so angry, I couldn’t even face him,” Ed remembers. “I turned away, and I ordered Sheri

to come with me. I was not going to stand there and make polite chatter after realizing that this man had just single-handedly

demolished all my savings—by not having fessed up from the head end what kinds of expenses we might be incurring.”

Roy Grimes, who doesn’t remember that incident, says he is astounded by Ed’s anger. When I told him about it—told him it was

still boiling after all these years—Roy called Adams Pest Control and had them send a copy of die termite protection contract

he had taken out on April 20, 1973, in order to sell the house to the Kramers. The Murphrees had given the Grimeses a similar

policy, but the company providing it had gone out of business. Apparently, Adams bought out the other company. There’s an

entry in Adams’s 501 Holly file dated October 10, 1971, indicating that the left side of the substructure was “badly damaged,”

and that the joists and subfloor were “badly damaged” In April 1973, Roy had Adams go under the house to install a four-by-four

subsill along the north wall. When that work was completed, Roy received the termite protection contract that he later passed

on to the Kramers.

The contract states that Adams would, for a period of one year, protect the property at 501 Holly “against the attack of subterranean

termites for the sum of $265.00.” The liability of the termite company wasn’t to exceed five thousand dollars. Inspections

would be conducted at least once a year, and the policy would remain in force for an annual fee of eighteen dollars. Ed Kramer

acknowledges having received the termite contract.

A Little Rock Realtor, when I told her this story, said there’s hardly any old house in this section of town that doesn’t

have

some

past termite damage. I told that to Ed. Could it be, I asked, that because this was the first house he’d ever bought, he

just didn’t know what he was getting into? Could it be that he was, and still is, being unreasonable?

“I don’t think so,” he says. “I asked them point-blank—I said, `Is there any termite damage in this house?’ and they said

no. That’s as straightforward as you can make it. I wasn’t saying, ‘Is this house termite infested?’ I was asking if it had

any termite

damage.

They said no, it’s been looked at, it’s been checked. Then to learn otherwise was a cold shock.”

He thinks about that for a moment, and then adds this coda: “They had been, ostensibly, Sheri’s good friends. I thought that

if

anybody

was going to be faithful and straightforward and honest to you, it would be somebody you had known since childhood. I felt

that they had betrayed that friendship to us.”

Roy Grimes just shakes his head. “If anything,” he says, “because we were selling to Rita’s friends, I wanted to bend over

backward to make sure everything was okay. I don’t know what to say. I’m sorry he feels that way. It’s just not the way I

remember it.”

Alicia was born in November 1973, months before Ed and Sheri’s disillusionment set in. They were still living in a magical

world then, and so they gave their daughter the middle name Thais, after that opera they had loved when they were courting.

Alicia Thais Kramer was the third child born to this house.

Looking at the Kramers’ scrapbook/photo album from the Holly Street years, I don’t see the disillusionment, of course. As

with houses, such stresses arc usually hidden. What I see instead is a young family enjoying their life and taking pleasure

in the memories they were making. Their album itself, an imposing corduroy and leather volume such as banks once used to note

their transactions, attests to the importance Ed and Sheri placed on the moments captured within: There are photos of Ed’s

productions at the Arts Center; news clips from the local press about Ed and the work he was doing; snapshots of everyday

family life. Ed made sure these moments were pasted down in appropriate order, and, in his role as official wit of the family,

he penned clever captions at the bottom of every photo: “Siggy getting ready to mow the lawn,” reads the line accompanying

a photo of Sig climbing on the lawn mower.