If These Walls Had Ears (33 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

A vivacious blonde twelve years Jack’s junior, Donna was bold and outgoing in her touch: They ripped out the old kitchen (finally!)

and started over, and when it was done the kitchen was green, with green paisley wallpaper on the walls and ceiling. Donna

covered the downstairs bathroom in a pink floral-print fabric, and it was padded. The shower curtain was made of the same

material. The upstairs bath was padded fabric, too, as was the big bedroom across the hall. Green, lots of green. My stepdaughter

Blair remembers that one downstairs room had green shamrock wallpaper, which Blair wanted to keep because her birthday is

March 17.

Jack doesn’t spend a lot of time pondering the finer points of decorating. “I don’t really care,” he says. “That was Donna’s

deal. Donna has two sisters, and all three are into decorating. They really work the flea markets hard. The sisters are into

what color is in now, and what’s out. Donna got into greens. And our house was green.”

Burglars seemed to see it that way, too. I don’t know how thieves choose a target, but maybe it has something to do with telltale

electronics boxes stacked by the curb—and access, of course. The Burneys provided both. They were cleaned out twice—burglarized,

looted, once while they were out buying even

more

things. It was just before Christmas that first year. They came home from shopping to find all the Christmas gifts gone,

as well as the TVs and stereos and VCRs. Another time, after a weekend at their condo in Hot Springs, they returned to the

same sickening scene. There was no tall fence around the backyard in those days, and thieves could kick in the back door and

empty the house under cover of a thick tangle of trees. After the second burglary, Jack had a wooden fence built, with a heavy

wooden gate. That stopped the problem.

And so the party roared on. Throughout the eighties, the Burney house was a magnet for people. Maybe the energy emanated from

all those electronic gadgets, but whatever its source, the result was palpable—LaughMan, EatMan, DrinkMan, DanceMan,

Party

Man

.

Donna had causes—one year she was president of the Advocates for Battered Women (“Had nothing to do with me,” Jack says with

a salesman’s nudge), and they held fund-raisers here. Donna, who loved to cook, invited her company’s executive staff for

elegant Christmas fetes.

This house was the after-school hub for most of daughter Andi’s friends, and even though Jack’s children—Butch, Brad, and

Bitsi— didn’t live with their dad, when Brad ran for president of his senior class, Jack and Donna threw banner-painting parties

here several nights a week. Andi and Bitsi were the same age and in the same grade, and all their friends were invited here

to breakfast after their senior prom. The breakfast was supposed to be outside, but that night it rained. About 1:00

A.M.

, hundreds of inebriated teenagers showed up, and Jack and Donna took them in. The kids sprawled all over the house in their

hot pink taffeta and pastel tuxes, wet mud caking their

peau de soie

heels and rented patent-leather pumps, not to mention the house itself. The house was a wreck the next day, but everybody

had a good time—including Jack and Donna.

There was even a wedding here once. In January 1982, four months after the Burneys moved in, Jack’s old roommate during his

bachelor days decided he was going to get married. He asked if he could say his vows in this homey house, in the living room,

in front of the fireplace.

It’s very hard to find home alone. When Jack married Donna, he’d become weary of the single life. He likes marriage, he says.

But then you get the other side of the coin: Marriage requires putting up with other people. Remarriage means even

more

people who fall into that category. Next thing you know, married people start thinking they’d feel at home if only they were

single.

Jack says that if he and his first wife had had three sons, there wouldn’t have been a problem. As it was, they had two sons

and a daughter. In junior high, Bitsi and Andi didn’t go to the same school. But by the fall of 1984, both were tenth graders

at Central High. The way Jack tells it, the girls competed for everything, and their mothers monitored the contest like a

pair of peckish hens. You can guess where Jack stood in all of this.

“The two mothers were the problems,” Jack tells me. “Not the daughters. You understand that?”

“Yeah,” I say, “I do.”

If one daughter made cheerleader, the other had to make it, or there was hell to pay. If Jack bought one daughter a car, he

had to buy the other a car, too—and it had to be just as

good

a car, or there was hell to pay. If Jack gave one daughter a credit card—as he did—then he had to give the other one a credit

card, and that was

really

hell to pay.

Cotillion was vitally important to the girls’ mothers. The lady who ran the program in those days, a Mrs. Butts, ruled with

an iron hand. You had to pass muster to get in. Boys hated it; girls and their mothers loved it. One way for a girl to get

in was to have an older brother who’d been in cotillion. So Jack forced Brad to pave the way for Bitsi. Bitsi got in, but

when they submitted an application for Andi, she was turned down. “Donna wasn’t happy about that,” Jack says.

One day, Jack was flying home after doing business in Atlanta, and a woman sat down in the seat next to him. She looked to

be in her sixties. When the flight attendants pushed out the beverage cart, Jack asked the lady if he could buy her a drink.

She accepted a glass of wine and he ordered a beer. They talked awhile, and Jack bought her another drink, and they talked

awhile longer.

Finally, he introduced himself. The lady turned out to be Mrs. Butts. “Mrs.

Butts,

” Jack said, “I’m so glad to get to visit with you. I’ve got a real problem.” When he got home, they resubmitted Andi’s application.

Donna was very pleased with the outcome.

The porch was where Jack usually went to work out his problems. He recalls sitting out there a lot, especially during the

mid-eighties. He sold his half of his business to his partner about then, and for a while he didn’t do anything. “It was the

most boring time in my life,” he recalls.

One day, he was just sitting on the porch, pondering his life, when he was interrupted from his reveries by a voice. There

was a man standing down by the curb. Jack didn’t know him. “Would you mind,” the man was saying, “if I came up and sat on

that porch with you?” Jack said no, come on. So the man did. They talked for a long time. “I’ve been walking past this house

for years,” the man said, “and I’ve

always

wanted to sit on this front porch.”

The problem for Jack is, the porch became synonymous with trouble, with bad times. I should have brass plaques made up:

This is where Siggy lost his finger,

on the door to the kitchen.

This is where Ruth’s heart was broken,

in the middle room.

This is where Sue and Myke’s marriage is buried,

on the front room floor. Forjack, I would affix the plaque to the porch:

This is where a Burney tradition ended.

It was on the porch that Brad told his father he wasn’t pledging Sigma Chi.

You may think this is frivolous, but Jack Burney is a man for whom such things still matter deeply. His older son, Butch—Jack

junior—had decided not to go to college. Butch, in his father’s words, was “a holy terror” as a child. “You name it, he did

it,” Jack says. In Butch’s young teenage days, the Vietnam War was still going on. “It was the era of the hawks and the chickens,”

Jack recalls. “He was into the long hair and everything. I was a hawk. I couldn’t believe anybody didn’t want to go to Vietnam.

I’ve changed a lot since then. But Butch would fight everything I believed in. He did a lot just to aggravate me.”

Butch was so notorious that when the younger kids got to Central and people asked if they were kin to Butch Burney, it was

just easier to lie.

He was a musician, an artist, and after high school he decided he wanted to go to Hollywood and become an actor. Jack pulled

strings and got him into Lee Strasberg’s acting school. So Butch went west. He appeared in one episode of

Happy Days

and in a few plays, but, says Jack, he was just so immature that he didn’t take advantage of the opportunity.

“So he came home and worked for me. For a few years, he gave me lessons five hours a day. He preached to me. Then he got married,

and his life changed.”

With Butch, Jack hadn’t had the chance to pass along the tradition. Brad, on the other hand, was the perfect son—never got

in trouble, made good grades, was class president. Jack refers to Brad as “Mr. Do-Right,” and it was only after listening

to the tape later that I got the feeling there was a slight jab inherent in that nickname.

“I was a Sigma Chi,” Jack says again. “President of the Sigma Chi alums. True-blue Sigma Chi. Donna, not growing up here and

not going to the university, she really didn’t understand that. And so when Brad went through rush, I stayed out of it. He

knew how I felt, but I stayed out of it. He came and talked to Donna about it, and she told him, ‘You do what you think is

best. Your father will understand.’ But it’s a guy thing. And so he came and told me one day that he had accepted Phi Delt.

It was a real disappointment. Took me a year to get over it.

“It happened right out here on the porch.”

The house itself was hard on Jack. And to be perfectly honest, he was a little hard on it, too.

He’s the first to admit he’s not a handyman. Two or three times, he fell down the Lee Street hill while mowing the lawn. That

in itself doesn’t make a person unhandy, though you might have a hard time convincing anyone who was watching. But Jack’s

problem seemed to be this: As a handyman, he was a salesman. He wanted the best deal, not the best job. “I’m always trying

to find somebody to do something,” he says, “always cutting corners on it, and it’s always the wrong thing to do type deal.”

There was a time in this house’s life when all the upstairs windows rolled open and every window had a screen. When Beth and

I moved in, we had ten of the window frames repaired and repainted and new screens put in; I think that job cost two thousand

dollars. We no longer have that kind of money for such details, so even today there are several windows upstairs that have

no screens. Fortunately, most of them don’t open, either, since Jack’s antidote to Andi’s and Bitsi’s nocturnal adventuring

was to paint the windows shut and cut the tree they would shimmy down.

But when the Burneys were first here, the windows would open, and they had screens. The problem was, the windows needed painting.

Real painters cost a lot of money, so Jack came up with a better way. “I had these two friends of mine, guys I had met at

the Instant Replay, where I used to hang out before I got married. Big group of us would go down there on Thursday nights

and we’d pick the high school football games. These two friends were kind of halfway unemployed most of the time. Good beer

drinkers, worked part-time.”

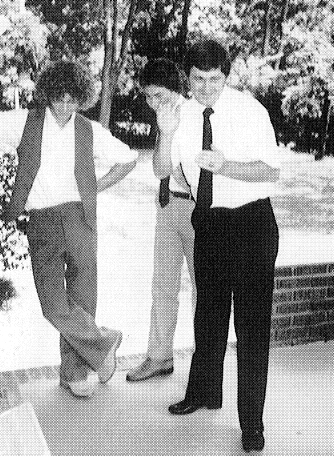

Jack and his sons, Butch and Brad. The Burneys threw a lot of Razorback parties in that side yard

.

Jack hired these two fellows to paint his house.

On the back porch, where Jessie Armour slept during the war years, Jack had a refrigerator that was only for beer. He doesn’t

drink anything else, but he

loves

beer, and he makes certain that he never runs out. That’s why he kept this refrigerator. Like a separate telephone line for

the fax, this was a dedicated fridge.

On the day the two painters showed up to start the job, Jack began a certain ritual. Every morning before he left for the

office, he would take four to six beers out of the beer refrigerator and put them in the regular kitchen refrigerator. “Boys,”

he told his buddies that first day, “there’s some beer in the refrigerator. Whenever you get through each day, go on in there

and get you a beer.”

One day he forgot. When Andi got home from school, the painters were upset. “Andi,” they said, “your daddy doesn’t have any

beer in here today. He forgot to buy beer.”

“No way,” said Andi. “He’s

always

got beer.” And she showed them the stash, which they proceeded to clean out.

Jack didn’t see them for several days after that. When they came back, he forgave them. Soon they progressed to the point

of taking the screen frames off and removing the screens. They were going to repaint the frames and rescreen them. But in

the middle of that job, they came to Jack saying they needed money to buy new screens. On the way to get them, they stopped

off to pick up a little beer. Then the police pulled them over and ticketed them for DWI. Jack never saw the screens and never

got his money back. And that was the end of his drinking buddies’ painting, because Donna fired them.

He tells me that story by way of explaining all those empty frames stacked up in my shed.

The Burneys actually had to finish the job of painting the house themselves. When it came time to sell, they decided the house

looked too dark sitting up on this hill half hidden by trees. It looked like a place Boo Radley might live in. What if we

painted it? they thought. Not just the woodwork but the brick, too?