If These Walls Had Ears (35 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

I bought this house myself, alone, for reasons I will explain in due time. My wrangling with the Burneys took place over just

a couple of days, but the tension lasted a month, from the beginning of September 1989 to the first of October. And longer,

I guess, since Donna won’t talk with me. They had listed the house for $129,900. On September 1, I offered $110,000 and stipulated

that they were to finish painting the house and porch and to scrape the paint drippings off the windows. I wrote in that I

wanted all ceiling fans, all window air conditioners, and the fireplace screen. I asked for a response by 1:00

P.M.

September 2.

They countered to $126,500—with an increase in earnest money—and stipulated that “3 green balloon shades in MBR will not stay.”

They demanded an answer by 8:00

P.M.

that same day.

I went to $117,000, agreeing to deliver the increased earnest money upon acceptance of the offer. The shades were no problem.

I imposed a 10:00

P.M.

deadline. I seem to recall that I went to $120,000 at one point, but I find no record of that. I also think they once called

off the whole negotiation, but I can’t be sure.

The last counter for which I have paperwork was for $122,000. I agreed to deliver the earnest money “1 day after acceptance.”

Looking back, I don’t know if that was just balm to ease the bruise of giving in, or because the day of deadline was a Sunday.

With that final offer, I also listed another requirement on their part—besides the normal termite contract, I specified “a

satisfactory structural report to be included.” My agent had known about the Landers episode and thus suggested this move.

The Burneys had to respond by 7:00

P.M.

September 3.

I don’t know what I would’ve done if they hadn’t taken the offer. A buyer was looming for my house in west Little Rock, the

house I owned with my now ex-wife back in Chicago and which I had been trying to sell for a solid year. I didn’t want to lose

that sale—even if it was for the same amount we had paid three years before.

But more than that, I needed that sale to end one chapter of my life and this one to begin another.

Jack and Donna accepted. And then the really unpleasant part began. They had more stuff crammed into one house than any couple

I had ever seen (until we started unloading

our

blended histories). My west Little Rock buyers wanted to be in by October 1 at the latest, which meant I had to have the

Burneys gone a day or so before that. Playing both ends against the middle, I eventually worked out a grueling closing date

of September 28 for both houses, with possession for both on September 29. For three and a half weeks that month, in four

dwellings in Little Rock, four groups packed boxes. At the head of the chain, the Burneys, I feel certain, cursed us all.

Before the closing took place, we discovered that the floor beneath our downstairs bathroom was rotten and would have to be

replaced. I frankly don’t remember paying much attention to any of this, which is sobering to me now, having just spent a

year observing how blinding a house’s charms can be—and to what devastating effect. Fortunately, I had a tough Realtor, Georgia

Sells, on my side. The Burneys wanted to pass us the standard Adams letter, with its exclusions. Georgia recommended that

I not accept that. We refused to close, and held off a day. In the end, the Burneys had to pay a different pest control company,

Terminix, to repair the damage underneath, and a floor man to repair the inside. The Burneys escrowed $1,981 for Terminix,

and $1,519 for the inside floor work. And I received a letter of clearance. Georgia says that deal reflects the new covenant

between buyer and seller, an understanding that’s become more prevalent over the past five years. “It used to be ‘Buyer beware,’”

she says. “Now it’s ‘Seller beware.’”

The painters arrived a day after we moved in. For the first couple of weeks, our furniture stood in a pile in the center of

the living and dining room, covered by a drop cloth. The workmen sanded and spackled and primed and painted, while Beth and

I planned a wedding and I wrote a magazine article. At night, after the girls had finally gone to bed, we would walk around

the house with drinks in hand, moving boxes to make paths, and we would marvel at the transformation that was taking place.

Gradually, the green Burney rooms receded into the house’s history, and the colors Beth and I chose together went on the walls

for all to see.

We married on a Saturday the third week of October. Two days before that, the men came to fix the bathroom floor. On the same

day, Brent flew in from New York, and my sons, David and Matt, came from their home in Connecticut. David brought his girlfriend.

My mother arrived from Mississippi. That night, we had a festive dinner, the first in our dining room. I was nervous—another

beginning—but toasts and speeches were called for. Beth, who once considered following in her family line of lawyers, does

these things better. I presented Blair and Bret rings with their birthstones, and Beth gave David and Matt sterling key rings.

On each one, she had attached a key to 501 Holly.

Our wedding took place downtown, in a wonderfully ornate vintage building where Beth and I had gone to dances. All four of

our children took part in the ceremony. Afterward, there was a party back at our new old house. Our friends were impressed,

we could tell. I had the lights just right to cast a glow off the terra-cotta walls. There were no cardboard boxes in sight.

Instead, the living room sparkled with the matching blue leather recamiers, the black lacquer bar, the Biedermeier mirror,

the fifties lamp and forties table, the deep red Sarouk rug. The dining room chairs ringed that room as guests served themselves

from a buffet adorning the old claw-andball table, which stood atop a blue Chinese rug older even than this house itself.

Our friends filled their plates and wandered through our rooms. They pushed open the French doors from the living room to

my office and stood in clusters, nibbling and sipping, studying the Arts and Crafts desk and the old lawyer’s bookcase and

the European sofa and the frayed Oriental rugs and the fifties table and especially the then-revolutionary fax machine, which,

from the moment I had heard about it, I had seen as a sign from God that, yes, I

could

live anywhere—even here and still be plugged into the world. Guests drifted onward into the bedroom, murmuring about the

black lacquer bed and the bird’s-eye maple dressing table and the thirties rattan chairs. And then they followed the inevitable

path into the Geranium Room, shocking in its audacity.

We danced some that night—pushed back the furniture the way Charlie and Jessie Armour had done so many decades before, when

this house was unscathed, though we knew nothing of the Armours then and, in fact, wouldn’t have paid them much mind if we

had. They were the past, and our dance was all about the future. We shimmied and shook, and then, as the guests dwindled and

our day slipped away, we swayed to Sinatra singing “Someone to Watch Over Me.”

The next morning early, I heard, even through my champagne stupor, a steady creaking on the stairs. It was just light outside.

I had no idea who was up. My sons and mother and stepdaughters were sleeping upstairs, and maybe Beth’s mother, too. Whoever

it was, I heard him thumping into furniture on the other side of the wall, and then total silence. I got up and put on my

robe. In the living room, I found Blair sitting on one of the recamiers in her pajamas, and she was glaring out the window

at the hazy gray light. Her arms were folded tightly across her body. I went over to her, the concerned stepdad, and sat down

in a chair next to her. She didn’t even look at me.

“What’s the matter?” I said.

Even today, I remember the way she looked at me, which was with hatred, and the way she spoke, which was a hiss. “What’s the

matter?” I said again.

She turned my way. “I should have

never

let you marry my mother.”

* * *

We lived our first years in this house electrified by undercurrents. One was the sputtering connection of old failed marriages.

Another was jealousy. Still another was the total shutdown power of grief.

Divorce doesn’t make the search for home any easier. It makes it possible sometimes, but never easier. The common term for

families who’ve been visited by divorce is

broken homes.

It’s an apt description. Divorce, once experienced, can infect the next house, and the next, and the next after that. It

can undermine foundations, weaken roofs, compromise the sanctity of the walls themselves. Once you know, it’s hard to forget.

If you know twice, it’s almost impossible.

Beth and I have been married for six years now, and we’re still working on blending, blending, blending. Blair and Bret, naturally,

being children, have played the usual cards— “I hate Jim. I want to live with Dad”—and by now I think we’ve gotten past most,

though not all, of that. For the first couple of years, when Blair would sulk and say she was “mad” at me, I would smile and

say, “So what else is new?” It became a running joke between us, and eventually her anger—at least her anger toward me—seemed

to dissipate.

But it’s not just those who are children, chronologically, who get caught up in the insidious power of past divorce. What

happens is this: After you’ve been burned, you tend to guard against being burned the next time. The problem is, with your

guard so high, you can’t see that you’re almost guaranteeing a repeat of the thing you dread most.

I had no sense of any of this until my first wife called me at work one Minnesota winter day and said she wanted to meet me

for a drink. Over a cocktail table, she told me that after eleven years she was unhappy and wanted a divorce. There was no

one else, she said. I’d been able to shut away the alien socks, but I couldn’t deny this. I had no idea at the time how profoundly

divorce would affect me. I was the last person in the world I ever expected to be

divorced.

It went against all I’d grown up knowing. Even though we had moved a lot, we were always together. Always a family. I was

old—thirty-two—to be learning this, but learn it I did: There’s no such thing as security. There’s no such thing as permanence.

You can know it in your head, but until you’ve experienced it, you don’t know it at all.

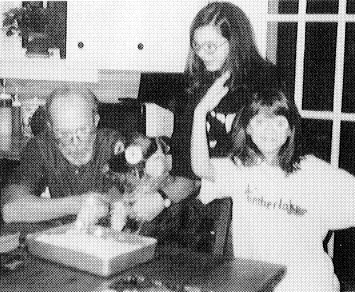

Jim, Blair, and Bret celebrating Snapp's third birthday, December 1994

.

We agreed to stay together for six more months, until David finished first grade. Somewhere, deep in a trunk in the darkest

corner of our attic, there’s a notebook in which I kept a journal of those excruciating months in that house in Minnesota.

It’s been twenty years, and I still don’t want to look at it. I do remember thinking that time had stopped. We could no longer

plan together, so we floated through the days and nights, untethered to anything—to the past we were giving up, to the future

we no longer had in common. We just treaded water. At least that’s what

I

did.

Then on the weekend of David’s seventh birthday, two moving vans came. Hers arrived first, and when they were finished, I

said good-bye to my wife and my boys and they drove off, bound for Miami. All of us were trying to be brave through our tears,

except for Matt, who was eight months old and didn’t understand a thing. He laughed the whole time.

When my van was loaded, I took one more walk through the house, through David’s red-white-and-blue room, through Matt’s yellow-green

garden of a nursery, through the icy blue living and dining rooms that now showed nail holes. When I was ready, I locked the

door and slid the key through the mail slot. Then I got into my car and went to meet the movers at my new apartment. Three

months later I got the letter from my ex-wife telling me she had remarried.

So when Blair said what she said to me that morning after the wedding, I understood. By then, I understood many things about

the way divorce affects our life in houses. For that very reason, I declined to have the girls call me Dad, as my ex-wife

instructed my sons to address her new husband.

But I’m not a hero in this cause. In addition to the decision to marry Beth and give up magazine editing, I had made another

decision in the summer of 1989: Never again did I want to have to move from a house because of a divorce. Never again did

I want to give up things that were dear to me. I had done it twice. I could’ve stayed in the houses, of course, had I been

able to raise the money to pay my wives for their share. But in the first instance, I wasn’t earning enough to do that. In

the second, there was too much equity involved.

So with 501 Holly, I decided to buy it myself. There was a bad moment with Beth, I remember, just as I was leaving her to

meet with the real estate woman. Beth asked if the house was going to be in both our names, and I said I didn’t know, that

I would ask the advice of the agent. But I knew already. This had nothing to do with my love for Beth. This had to do with

that thing I mentioned at the beginning—my bone-deep knowledge of the way life hears on living things.