If These Walls Had Ears (7 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

Nu Grape was going well. Over at the White City pool, you could hear young girls say, “If you can swim all the way across,

I’ll buy you a Nu Grape.” The distinctively cinch-waisted bottle certainly helped. “She has a shape like a Nu Grape bottle”

was another popular saying—usually from the young men watching those girls swim in the pool. But though business was good,

Charlie decided he needed a gimmick. Selling had gotten sophisticated. With radio, the public had lots of new demands on their

attention. You had to reach out and

grab them.

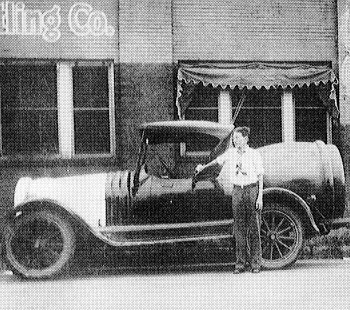

The idea Charlie came up with was to build a car in the shape of a Nu Grape bottle.

He began with a Chevrolet chassis, but by the time Charlie got through with it, you wouldn’t have recognized it as a Detroit

product. Actually, the car became a kind of work in progress. At first, it didn’t have the roof I saw in that first grainy

photograph—just two seats up front and a back end shaped like the Nu Grape bottle. The radiator looked like a bottle cap from

the start. Naturally, the car

had

to be painted purple. The back opened so Charlie could carry cases of soda, or proposals, or whatever a Nu Grape bottler

needed to have on hand. Immediately, the car achieved Charlie’s purpose—people all over Little Rock knew about “the Nu Grape

car.” It was good for business. As for Charlie’s image, he had finally acquired a degree of that Southern eccentricity he

had admired so in Louisiana.

He took to driving the Nu Grape car back and forth to work every day. At night, he would park it out in front of the house

so people couldn’t miss it. In the mornings, before he went to the office, he would drop Charles and Jane off at school. Poured

them out with everyone watching. They weren’t the least bit embarrassed. They loved the car, found it enormously funny. Their

classmates considered Charles and Jane celebrities because of it. The car also advertised the fact that Charles and Jane had

a never-ending supply of soft drinks cooling in their icebox at home. After school, 501 Holly was a very popular hangout.

To help sell soda pop, Charlie Armour create this car shaped like a Nu Grape bottle. fane and young Charles here—outside his

dad's bottling plant—love it.

Eventually, Charlie decided that having no top on the car was impractical. He commissioned a canvas top, with curtains that

could be locked into the windows on cold or rainy days. He even installed a primitive heater. All this “winterizing” belied

an ulterior motive. There was to be a bottlers’ convention in Buffalo, New York, and Charlie wanted to drive his purple pop

bottle the two thousand-plus miles to Buffalo. Not only that, he wanted Jessie to go with him.

She thought it was the most ridiculous thing she’d ever heard. This was a

gimmick,

not an automobile. And highways were unpredictable, not to mention unpaved. Jessie’s world didn’t allow for such tomfoolery.

She lived a swirl of meals and sewing and grocery shopping and child rearing and club work. She belonged to the Culture Club,

one of the finest women’s organizations in the Heights. She also taught a young women’s Sunday school class at Pulaski Heights

Presbyterian Church. Yes, she had a maid, a Negro woman named Mabel, but Mabel wasn’t always dependable. She lived out in

back over the garage, and though she was good when she was working, sometimes she would just leave. She once went to Brownsville,

Texas, for a year. Then, one day, she showed up again, asking for her job back. Jessie gave it to her.

So Charlie had to woo Jessie about the Buffalo trip. He was persistent, and he could be charming. He would take everybody

for drives on Sunday afternoons, making sure Grandma had a blanket to cover her legs. Sometimes he would surprise the family

by buying tickets to the Majestic Theater downtown. It was a movie theater with vaudeville shows between the films, which

were still silent. Jessie and Grandma Jackson loved the Majestic, losing themselves in the flickering pictures while the piano

player matched the mood. The kids loved the vaudeville acts, because if you went on your birthday, you got to sit in a special

box and the entertainer would come over and talk to you. Charlie would usually get tickets for Friday or Saturday nights,

the best nights, when it was reserved seating only.

When time for the convention finally arrived, Jessie went. It took

days

each way. She was exhausted when she got home, but Charlie was beaming. His Nu Grape car had been the talk of the show.

* * *

In the spring of 1926, Charlie received a letter saying that his mother was coming to live with them. This was not considered

good news.

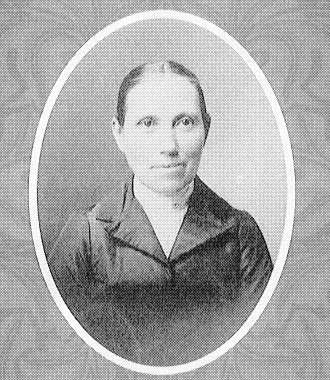

A severe, humorless woman, Elizabeth. Leverton Armor spelled her surname like warfare—minus her son’s softening

u

. Charles and Jane didn’t remember her, so Jessie told them stories of when Grandfather and Grandmother Armor had visited

in Fort Smith when Charles and Jane were little, or even before they were born. Grandfather Armor’s name was Charles Webster

Armor. He had fought in the Civil War on the Union side, and he loved to tell stories about his exploits. Whenever the Armors

had visited Fort Smith, Mr. Armor was the center of attention for the duration of the trip. He was a character, a raconteur.

As a young man, he had ridden for the Pony Express. That was a very dangerous job, Jessie told Charles and Jane—both of whom

were spellbound by this rambunctious relative they had never really known. They wished he were coming instead of his widow.

Jessie told them they were to address Mrs. Armor as Grandmother Armor—

never

Grandma. What she didn’t tell them was that Charlie’s mother was a strict, straitlaced, ill-tempered old biddy and that Grandfather

Armor’s most perilous exploit had been living with her.

Charlie, meanwhile, had more practical concerns—such as where to put everybody. This house just wasn’t large enough for another

person. And yet they loved it here and didn’t want to move. One night at supper, Charlie announced a bold plan. “What we’ll

do,” he said, “is add on.”

In August, he and Jessie borrowed money from the Prudential Insurance Company, and the work began immediately. Architect Ray

Burks recommended adding a second level at the back of the house. Charlie wanted to add three bedrooms and a bath—and, by

now, some good-size closets. As before, they didn’t stint: on details. The upper floor would be reached by the stairs that

previously had gone to the attic. At the top of the stairs, you took a right and there was a small bedroom with casement windows

on the east and south sides. That room was connected by French doors to a larger room with windows all across the south wall

and two more on the west side. This room also had a huge walk-in cedar closet. The plan was for Charlie and Jessie to move

up here, and Jane would take the small room adjoining. Across the hall was a nice-size bedroom for Charles. It had windows

on the east and north walls, so that when you woke up in the morning, you felt as though you’d slept in a tree house. A door

in Charles’s room led to a bath with a pedestal sink and a beautiful black-and-white tile shower. Charlie, Jessie, and Jane

could also get to that bathroom by a door that opened to the hall. It was a well-thought-out floor plan. Carolee would need

a place when she came home to visit, so she and Grandma Jackson would keep their rooms, and Grandmother Armor could have the

middle one that Charlie and Jessie had been using. Until the new addition was finished, everybody would just have to make

do.

Elizabeth Armor arrived, as best can be determined, with the chill of autumn. It was a difficult fall, with all the dust and

noise and the workmen tramping in and out. Then, too, there was this stranger in their midst. Jessie did her best to soothe

frayed nerves. There was little entertaining because of the work, but she cooked up great steaming platters of comforting

foods for the family. Grandmother Armor, with her mouth set hard and her hair bound in a bun, was not comforted. At suppertime,

if Jessie served her something she didn’t like, instead of eating it graciously, she would take her index finger and slowly

push the plate away. The children found her impossibly strict and unapproachable—as opposed to their Grandma Jackson, who

fried them doughnuts and read to them and occasionally talked Jessie into letting them go to the picture show. Grandmother

Armor had little use for anybody, much less children.

Elizabeth Armor, Charlie’s mother.

The Addition was finished by Christmas. That year, 1926, Uncle Ben, Grandma Jackson’s brother, came to spend the holidays

in Little Rock. He was on his way to the Hawaiian Islands, just another in a long list of his exotic jaunts. The man travelled

almost as much as he practiced medicine. Charles and Jane loved it when Uncle Ben would come. He was so funny when he talked

about the places he’d been. The truth was, he was kind of a snob about travel. Once he had come to see them after a trip to

Venice. All he could talk about was how bad the place had smelled.

Grandma Jackson was overjoyed to see him. She wanted to show off her new radio, not to mention their new house. She was seventy-four

that year, and her health wasn’t all that she wished. The asthma was getting worse—even though Jessie sent notes with the

Christmas cards saying Grandma was “spry as a cricket.” Cynthia and Ben sat by the radio for hours that year, listening and

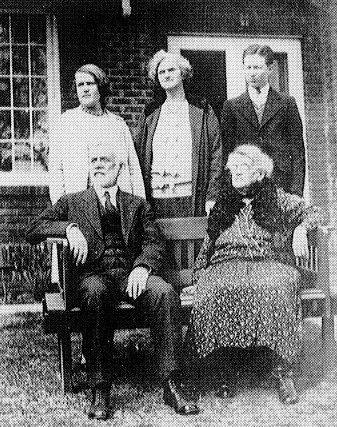

talking, reminiscing. It was a wonderful Christmas. The new addition, made of stucco and painted white, sat atop the old structure

like a big white cake from Jessie’s kitchen. On Christmas Day, the family posed outside in the yard—everyone but Carolee,

who wasn’t there, and Charlie, who took the picture, and Grandmother Armor.

Christmas Day 1926, Despite Uncle Ben's visit and the house renovations being completed, nobody in this picture seems to be

having a happy holliday.

Looking at that photograph, you’d never know it was a happy occasion. A frown creases every face. It’s as though a vague communal

uneasiness had now permeated this house, filling each member of the family with an unnamed dread.

Only Jessie, indomitable Jessie, seems to be trying to summon up something resembling a smile.