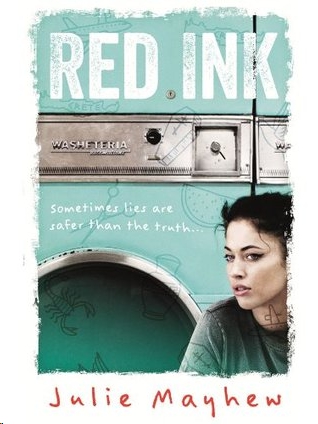

Red Ink

Authors: Julie Mayhew

Table of Contents

For Will and Ollie

“History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.”

Philip Guedalla, 1920

(repeating Dr Max Beerbohm, repeating Quintilian)

This is the recipe.

Take five pounds of hulled whole wheat. Hold it in your arms. Feel that it weighs nothing compared to the load that lays heavy on your heart. Wash the wheat, let your tears join in. Strike a match, strike up faith, light the gas. Watch the wheat bubble and boil. See steam rising like hope. Take the pot from the heat and pour the wheat through a sieve. Lay the grain on a sheet overnight to dry. Rest your head on your own sheets. Dream of a flower dying, shedding its seeds, allowing another flower to grow.

In the morning, on the day of remembrance, put the wheat in a bowl with walnuts, almonds and parsley. Add a message of devotion, a wish for the future, your gratitude to God. Sprinkle in cinnamon, not guilt. Throw in sesame seeds, throw away your fear. Turn out your mixture and create a mound – a monument to love. Brown some flour and sift. Add a layer of sugar. Press flat. Finally, crush the skin of a pomegranate with the remains of your fury and spread the seeds with love, in the shape of a cross.

Maria did not dream of a flower dying. The night before her mother’s funeral, she did not sleep at all. She pressed one of Mama’s cardigans close to her face, letting it transport her back to a farm where cistus shrubs turn the air bittersweet. She listened to Melon’s snuffling breaths, envying the way her daughter remained untouched by grief. She thought of the day ahead, the day she would return her mother to the earth. She was not ready to let her go.

Auntie Eleni had outlined the ceremony and recommended a plot. She had also pressed into Maria’s hands the pamphlet containing the recipe for the traditional

kollyva –

the boiled wheat.

“But I can’t cook,” said Maria, scanning the recipe. “I can’t do it.”

“You will find it within yourself,” Eleni insisted.

And so she had.

17 DAYS SINCE

“You okay in there?”

I locked myself in the bathroom two hours ago.

“Yeah.” One syllable is all he can have, otherwise he’ll think we’re mates.

“You’re very quiet.”

“I’m fine.” Two syllables. He should think himself lucky.

My name is Melon Fouraki. Let’s get that out of the way, straight off. Some kids get their parents’ jewellery or record collections as hand-me-downs. Mum gave me this name. It is one of her memories – she was brought up on a melon farm in Crete. I’d rather she’d given me her old CDs. She also gave me Paul. Living with him is like wearing clothes made of sandpaper. Every move I make, I’m on edge. He watches so much it hurts.

The bathroom is the only place to get away. I can hear him fidgeting on the hall landing outside, pretending not to be there. I can hear him bothering the floorboards. He’s listening through the door for the sound of a fifteen-year-old trying to slit her wrists. I am not going to slit my wrists. Paul is a social worker, so he thinks everyone my age runs away from their care home, sleeps on the streets, turns to crime, gets taken back into care and then tries to kill themselves. He can’t get his head around the fact that I am well-balanced. They worked with each other, Paul and my mum, only they ended up shagging. He would say they were partners. ‘Partners’. Idiot. He thinks they were proper boyfriend and girlfriend but he’s deluding himself. Mum only hooked up with him because she thought it would freak out the rest of Social Services if the Greek woman and the black man got it on. It’s not as if they were living together or anything. Now Paul has moved in to look after me. How ironic. How tragic.

My mum is dead. Seventeen days ago it happened. Paul thinks I need sympathy and care and time and asking every five minutes how I am. I don’t. Just because your mum is dead that doesn’t define you or anything. I am my own person.

Paul is still outside the door. I can’t concentrate on writing in my book with him there.

“You’ll turn into a prune if you stay in much longer.” He is trying to sound casual and funny, as if me being locked in the bathroom is the most hilarious thing in the world and not a total crisis. He is picturing me collapsed in a bath of pink water, a razor on the edge of the tub, my eyes rolled back in their sockets. I’m not even in the bath. I just ran the water so Paul would hear and not question what I’m doing.

“Yes. All right,” I yell back. Three syllables. Bugger.

I double-check the bathroom lock, make sure I fastened it, just in case Paul wigs out and decides to burst in on some kind of rescue mission. Mum fitted that hook-and-eye lock. That’s why it’s wonky and why the screws haven’t been pushed in all the way. If you lean on the door, it opens up a crack, like our front door with the chain on. If Mum was ever outside the bathroom wanting to know what I was doing, she would shoulder the door and stick her nose through the gap. Paul won’t do this, not unless he really gets a real panic on. As far as he’s concerned I’m naked in here, and he’s a middle-aged social worker who’s dead cautious about doing anything that might seem dodgy.

I was at Chick’s house when the police came knocking. Chick’s real name is Kathleen but everyone calls her Chick because she’s little and scrawny and kind of sweet at the same time. No one calls her Kathleen to her face, except for grown-ups. Kathleen’s a geek’s name. Mum was always moaning that I spent far too much time at Chick’s. She never liked Chick’s mum, Mrs Lacey. She thought she acted all superior just because she has a part-time job making up the names for emulsion paint. You know, Pistachio Dream, Cerise Sunset, Arsehole Brown, that kind of thing. Mum said it was a ‘pointless’ job, but I thought it was kind of cool to be paid to do something so, well, pointless. Anyway, I was at Chick’s house when the police came looking for me and I wonder whether Mum subconsciously did it on purpose, chose to get knocked over that evening just so she could prove her case about me spending too much time around Mrs Lacey. That’s the sort of thing she would do.

Once when we were in Crete visiting Granbabas, one August when it was so hot you couldn’t breathe without cracking a full-on sweat, she made me sit with her in the cashpoint lobby of a bank in Hania, just because it had amazing air-conditioning. We looked such losers, sat in those deckchairs we’d brought with us, the kind that make your knees touch your chin when you sit down. The locals came and went, swiping into the lobby with their cash cards, getting their money, giving us weird looks, wondering if we were the bank manager’s mad relatives minding the cash for him. Mum sat with her legs stretched out, her head tipped back, like she was sunbathing indoors. She kept doing these big, long, God-it’s-so-hot sighs even though it got quite chilly in there after about half an hour. I would have given anything for a stroppy bank clerk to have moved us on, but it was Sunday. No staff. We stayed there for three hours. Mum fell asleep and, because she’d kept her sunglasses on, I never noticed her eyes were shut.

Paul still won’t shift from the door. “Well, I wouldn’t mind a bath later, so . . .”

“So?”

“So, don’t use up all the hot water, please, Melon.”

He’s still there, waiting. I get up from the floor, kneel over the bath and swish my arm in the water. I hope the noise will prove that I’m still breathing and all my main arteries are intact. I listen for Paul’s feet on the landing. There is a creak or two, a pause. He’s thinking about saying something else, I can feel it. Nothing. Then the

crunch, crunch, crunch

of the loose boards under the stair carpet. He’s gone. At last. I sit on the mat with my back up against the bath. The side of the bath is carpeted. Old mauve shag-pile. The bathroom suite is green and there is a limescale stain from the bath taps down to the plughole, like tea running down the side of a mug. Mrs Lacey’s bathroom is beige with a sandstone mosaic.

Now that Paul has gone I can write things down. That’s why I’m in here. I don’t want Paul to see what I am doing. He will think that it’s a ‘positive step’. He will think it shows I’m ‘coming to terms with everything’. He will think I am close to embracing him in a big, old, do-gooding hug. Basically, he wants me to cry. I do not want to cry. I don’t need to cry. ‘It hasn’t hit you yet,’ he’ll say. And I’ll make some joke like, ‘No, maybe not, but it’s definitely hit Mum though, hasn’t it?’ Ha ha ha ha. And he’ll pull a face and look like he is trying not to blub. This is mean of me, I know, but I just want to be left alone. If Paul can’t understand that, he’ll have to face the consequences. If only Mum had waited one more year, I’d have been sixteen and allowed to look after myself.

I can hear the scrape of a saucepan bottom against the hob coming from the kitchen downstairs. Paul is a noisy cook. A show-off. He has been cooking all evening, in between his panic attacks outside the bathroom door. He is always cooking for me. He thinks he’s filling the gap left by Mum, but she never used to cook much. Frozen stuff, pasta sauces, lots of things on toast, that’s what I’m used to. Tonight it is homemade soup. I don’t want to have these meals with Paul. He tricks me into them. He’ll ask, all casual, ‘Do you like soup?’ (or risotto or bolognese or whatever) and I can hardly say no otherwise I’ll never get to eat that particular food in front of him again. So I go, ‘yes,’ and he goes, ‘good, because that’s what we’re having for dinner tonight,’ and that’s it, I’m stuck with it.