Dickinson's Misery (30 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

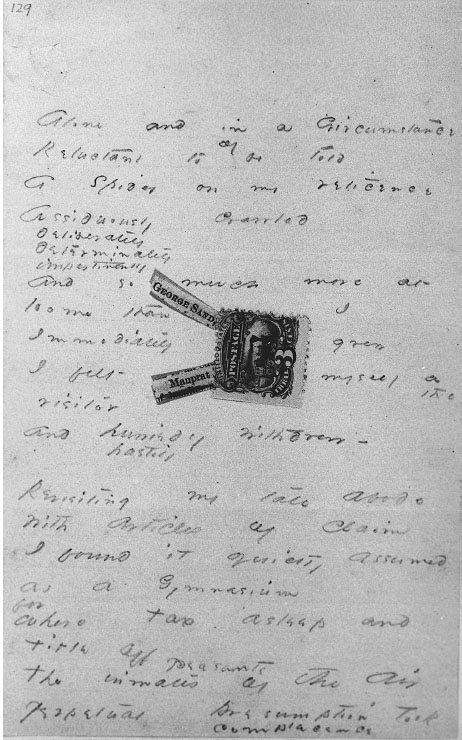

Figure 25a. Emily Dickinson, around 1870. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 129).

Figure 25b. Emily Dickinson, around 1870. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 129).

In order to answer that question, we might begin by posing another. Do the eccentric materials sometimes pasted on or enclosed within Dickinson's writing really

matter

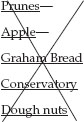

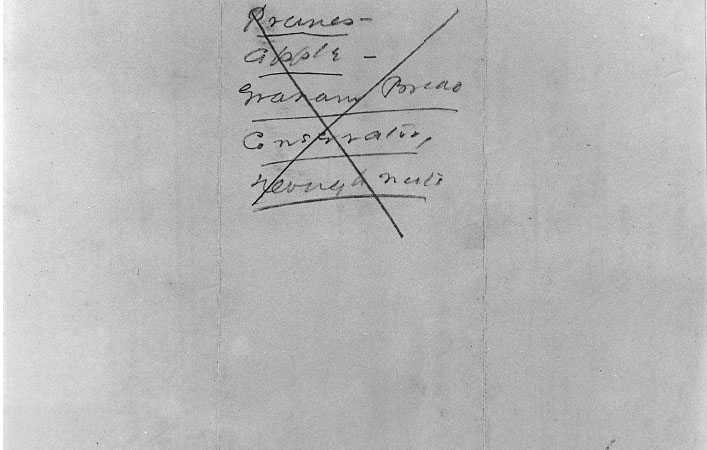

to the poetry that has been read off of them? In some ways, no. The pencil draft of “After a hundred years” (F 1,149), for example, could not be said to refer to the domestic list on the back of the page on which it was written (

figs. 26a

,

26b

):

After a hundred years

Nobody knows the place

knew

Agony that enacted there

Motionless as Peace

_______________________

Weeds triumphant ranged

Strangers strolled and spelled

At the lone Orthography

Of the Elder Dead

____________________

Winds of Summer Fields

Recollect the wayâ

Instinct picking up the Key

Dropped by memoryâ

verso:

All that these two texts have in common is paper. After a hundred years, the poem has passed into the cultural memory instituted by literature; the miscellany has been consigned to the scholar's documentary interest. Yet precisely for that reason, it is the latter that may affect us now with some of the uncanny power contained in the lines' central pun on reading. The “Strangers” who discover the traces of the dead in Dickinson's version of the country churchyard are “spelled” from their stroll by stopping to read them; in order to do so, they must “spell” out “the lone Orthography” that indicates the dead's now “Motionless” presence; so spelling, these strollers may fall under the spell of the dead's strangeness. That effect depends on an act of deciphering that is epistemologically incomplete, since it cannot grant the dead new life: these are strangers after all, with no direct experience of the past and the “lone Orthography” does not, in the poem, eventuate in the proper names of “the Elder Dead” (except, perhaps, in the initials E. D.). The readers in and of these lines thus speculate in specular fashion, doubly identified and doubly self-estranged by their interruption by the spirits of “the place.” In this place, the pathos of history (“Agony that enacted there”) has been reduced to an inscription only “Winds” know how to readâwhich is to say that no one does. The habits of “memory”âreceived modes of identifying writing and reference in the person of a living subjectâhave been displaced by an “Instinct” that hovers between perception and cognition, between the musical “Key” one might hear on the wind and the “Key” to a foreclosed interpretation.

In both of these examplesâin attempts to read the blue stamp stuck to printed proper names and in Dickinson's fiction of the no-longer-legibleâwhat is missing is the established literary character that will inevitably influence actual readers who encounter Dickinson's work not in these conjured places but in classrooms, anthologies, and editions. The truth is that we know too much about “Emily Dickinson”âpoet, recluse, Myth of Amherstâto be able to imagine her “Orthography” as anything stranger (or more historically distant) than the traces of a subject who will already have been remembered. As Randall Jarrell wrote fifty years ago, “after a few decades or centuries almost everyone will be able to see through Dickinson to her poems.”

4

But maybe it works the other way around: after a few decades or centuries almost everyone will be able to see through the poems to Dickinson. That would be remarkable, since for over a hundred years, it is poetry that has been successively personified by versions of Dickinson: by the isolated private genius composing only for herself; by the neglected protomodernist writing for an audience she had yet to create; by the artist crafting gems of timeless hermetic verse; by the renegade subverting the precepts of her society; by the woman working against the grain of patriarchy; by the writer taking up and forging a women's literary tradition; by the lesbian retreating from and challenging straight norms; by the privileged white woman addressing her familiars from the comfort of her big house; by the one-woman avant-garde small press. The recursive logics of the lyric genre in which Dickinson's work has been received and of the gendered identity that has served to narrate her relation to that genre inevitably implicate the person in the poems.

5

Even if one were to show that Dickinson's writing was largely citational, thoroughly textual, intricately dialogic, and historically material, its subject would still “spell” Emily Dickinson.

Figure 26a. Emily Dickinson, about 1868. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 126, 126a).

Figure 26b. Emily Dickinson, about 1868. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 126, 126a).

Feminist theory has been vitally concerned with the forms of personal survival available in women's writingâ“vitally” so since the rationale of feminist literary studies is at stake in them.

6

At least since the 1970s, Emily Dickinson has personified American feminism's investment in personal reference, and her writing has personified “a genre,” as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar put it, “that has traditionally been the most ⦠assertive, daring, and therefore precarious of literary modes for women: lyric poetry.”

7

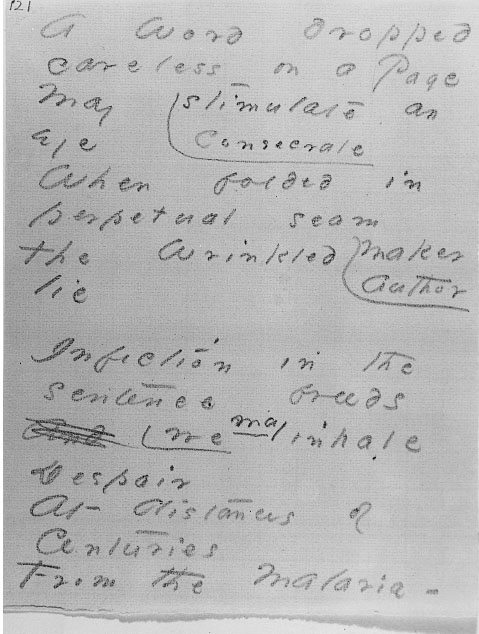

Gilbert and Gubar's view of the lyric as self-referential had, as we have seen, a long history, but their view of the genre as “assertive” was their version of that history, and it followed from their Bloomian argument that the Anglo-American literary tradition is agonistic, and that to enter the literary field is, for a woman, a personal battle. On this logic, the more personal the genre, the braver the battle. Thus the conclusion of their argument took place over the body of Emily Dickinson, a body they identified not only with definitions of gender and genre (and gender in genre), but with a strangely anatomized version of writing itself. In their reading of the well-known lines that begin “A Word dropped / careless on a Page” (

fig. 27

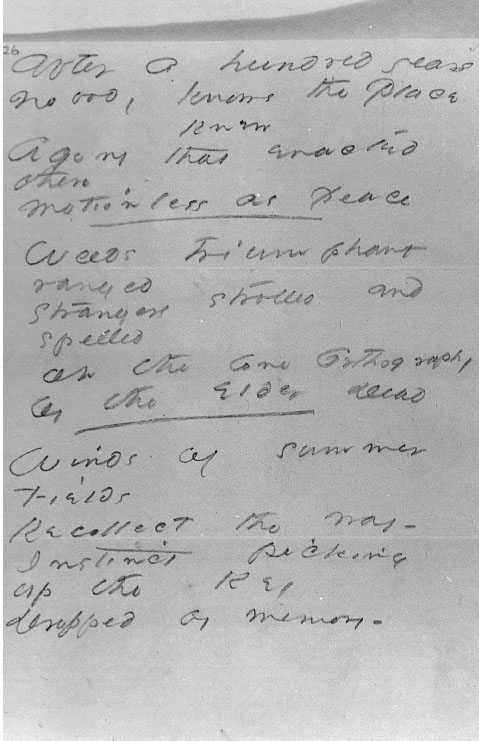

; F 1268)â

A Word dropped

Careless on a Page

May stimulate an Eye

Consecrate

When folded in perpetual seam

the Wrinkled Maker lie

Author

Infection in the sentence breeds

And

we

may

inhale Despair

At distances of Centuries

From the malariaâ

8

Figure 27. Emily Dickinson, about 1872. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 121).

âfor example, Gilbert and Gubar suggest that

for any reader, but especially for a reader who is also a writer, every text can become a “sentence” or weapon in a kind of metaphorical germ warfare. Beyond this, however, the fact that “infection in the sentence

breeds

”

suggests Dickinson's recognition that literary texts are imprisoning, fever-inducing; that, since literature usurps a reader's interiority, it is an invasion of privacy. Moreover, given Dickinson's own gender definition, the sexual ambiguity of the poem's “Wrinkled Maker” is significant ⦠even the maker of a text, when she is a woman, may feel imprisoned within textsâfolded and “wrinkled” by their pages and thus trapped in their “perpetual seam[s]” which perpetually tell her how she

seems.

9

If Porter imagined the “invasion of privacy” described by the lines that begin “Alone and in a Circumstance” rather literally as a bug on the poet's privates, Gilbert and Gubar imagined literature as a figurative bug

in

the poet's privates. The stunning idea that “literature usurps a reader's interiority” exaggerates the phenomenology of the intersubjective confirmation of the self that we have noticed in nineteenth- and twentieth-century lyric reading; what is fascinating here is that overhearing a lyric voice or performing a lyric script has modulated into catching a lyric disease. Further, the critics' vocabulary of agency (“weapon,” “warfare,” “coercive,” “imprisoning,” “fever-inducing,” “usurps,” “invasion”) overwhelms Dickinson's metaphor of disease and its pathos of indeterminate agency, turning a condition passed accidentally from one body to another into a narrative of the subjection of one body to another.

10

The body that is not Emily Dickinson's in this lurid scenario is the body of

literature.

But literature has no body. That may be why in another curious turn, Gilbert and Gubar stopped making literature an organic agent of violation, instead turning the poet into “wrinkled” paper, subjectively mirrored and “trapped” by pages that “perpetually tell her” aboutâof all thingsâherself. In literature, intersubjective confirmation seems to work both ways.