Dickinson's Misery (27 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

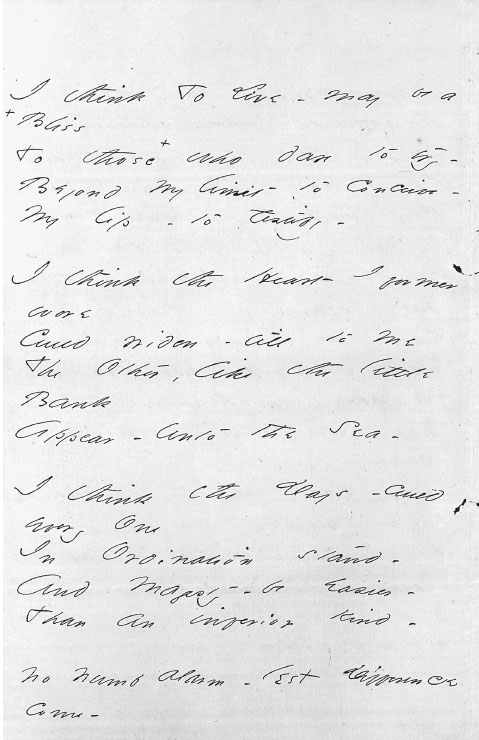

Figure 21a. From fascicle 34 (H 50). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Figure 21b. From fascicle 34 (H 50). By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The first of these lines, especially in the variant version, echoes directly the tautology that launches the lines that begin “I cannot live with youâ.” In this sense, one line may be read as a variant of the other, or the two sets of lines may be read as proliferating variations on the same themeâthough what that theme might be it is hard to say, and it is even harder to say why it seems to require so many variations. Cameron, the best reader of Dickinson's variants, has provocatively suggested that “by amplifying the idea of a subject to include its variants as well as variant ways of conceiving it [Dickinson produces] utterances that are extrageneric, even unclassifiable. And (for that reason, in a way that it seems to me no one yet has quite explained) untitled.”

42

These lines, at least in manuscript, are certainly “extrageneric,” but are they an “utterance”? Dickinson's lines have often been

read

by literary critics as represented speech, even when readers try to make their graphic, genre-breaking, “untitled” moves more apparent. Mary Jo Salter typifies the assumption that even variant lines represent the properties of voice when she writes that Dickinson's variants “may have represented to her either revisions or ⦠overtones: that is, each well-chosen alternative was at least as right as any other, and possibly most beautiful when held in mind with the other(s), like a chord.”

43

Yet Cameron's emphasis on the intersubjective, extrageneric quality of the variants also urges one to attend to the words that crowd the bottom of the second page of the manuscript as something other, something stranger, than “utterance,” in one or several voices. As Dickinson put it in a letter to Higginson, “a Pen has so many inflections and a Voice but one” (L 2:470). Perhaps so many inflections of the pen riddle the page of “I think To Liveâ” because to inflect

that initial tautology is the lines' problem. What “I think To Liveâmay be a /

x

Bliss [

x

Life]” and “I cannot live with Youâ / It would be Lifeâ” share as redundant propositions is the implication that were the possibility of presence not foreclosed, all one could say would be “LifeâLifeâLifeâLifeâLife” over and over in a blissful stutter. Put another way, the desire that informs these lines is the desire that they need not be written.

But the lines were written, of course, and so inflected with a desire that diverts the crisscrossing hesitations with which they begin by almost ending. They do proceed, but in a direction that is anything but linear. Loop by metric loop, the lines of “I think To Liveâ” turn back upon that opening line as if locked by the Sexton's key within its syntax. The lines assume the burden of defining an infinitive that has already been defined as indefinable: “Beyond my limit to conceiveâ / My lipâto testifyâ.” What the rest of the lines bear witness to is the attempt to write the unsayable, to inflect an ideally uninflectedâexperience? sense-certainty? “Life,” as the term appears here, is an ontological absolute. “Had we the first intimation of the Definition of Life,” Dickinson wrote to Elizabeth Holland, “the calmest of us would be Lunatics!” (L 2:492). Not being able (or refusing) to define

what

it is, the lines go on to decline

where

Life “may be” if “it would be.” That proleptic “may be” places what follows in the perspective of anticipation, so that what “may be” would be conceivable only in terms of what was: “the Heart I former / wore,” “an inferior kind” of time. This entanglement of anticipation and retroaction predicated in the first nine lines by the repetition of “I think” gives way to another anaphora: “No ⦠/ No ⦠/ No ⦠/ No ⦠no ⦔ We could read the retrograde progression from the ninth to the twelfth lines as a (failing) attempt to extricate thinking from the temporal trap in which the grammatical structure of address has thinking locked. In those lines, “Difference” has already come, the “

x

start [

x

click] in Apprehension's Ear” has already been registered. The “click” (of the key?) in the variant interrupts the first lines' grasp (apprehension) of what it “may be” “To Live” and marks their suspicion (apprehensiveness) that that

what

is outside the reach of languageâor of writing. When the fifth stanza then seeks to deny the denial of the fourth, its “Certainties” are made less certain by the differential (that is, written) framework that they claim to transcend. While the alliteration and subtle assonance of the lines strive to give the impression of sameness (an impression located in their acoustic effects: “Certainties ⦠Sun” / “Midsummer ⦠Mind” / “⦠steadfast South ⦠Soul”) “Sun,” “Midsummer,” and “South” are themselves only articulable in their difference from the “⦠Polar timeâbehindâ.” The address, still enmeshed in the tragic temporality of a retroactive anticipation, cannot name the place beyond this predicament until its last two spare monosyllables: “in Thee.” The figure of address is

revealed in the end to have been the “what,” the subject, that the lines have anticipated all along. In Helen McNeil's reading, “âThee' is whatever would give the mind whatever the mind desires.”

44

At the end of “I think To Liveâ,” the deferred designation of “Thee” is not, however, merely the vehicle of desire's fulfillment; “Thee” is the name

of

desire, its unlocatable location. Or perhaps we should say its suspended location, for it is in the end at the dead center of the chiasmus between “the fictionâ /

x

realâ[

x

true]” and “The

x

Real [

x

Truth]âfictitious ⦔ When desire's prolepsis “So

x

plausible [

x

tangibleâ

x

positive] becomes” that desire “seems” answerable, its object is canceled by the rhetorical crossroads at which that object is sublated in “seems.” That suspension is in effect a refusal to sublimate “Thee” by apprehending the other in figureâthat is, to forget that its plausibility would be an effect of the apostrophe that the lines defer. Why go to so much trouble to put it off? In a different mood, Dickinson might have mediated desire's life-anddeath alternatives by substituting an enclosure or an allusion or, perhaps, a drawing of a tombstone like the one she penciled on the back of a fragment of stationery (

figs. 22a

,

22b

) that reads,

But the lines that begin “I think To Liveâ” just keep doubling back on themselves. Why would Dickinson want to mark and remark, reach toward and away from the object of these lines' address, to stage such a pathetic near-miss? The apostrophe that works retroactively to bring the object of address closer is qualified by its position at the edge of the lines' temporal grasp. Captive of neither the Imaginary “Other” self with which the lines begin nor of the Symbolic register they surround, “Thee” is in the position that Lacan came to name the Real: that point on the horizon of language that sets desire (or language-as-desire) in motion but which language (or the subject constructed from it) cannot (in order to keep desiring) apprehend.

46

To do so would mean to stop desiring, or to stop livingâor to stop writing and rewriting.

What this reading of “I think To Liveâ” allows us to understand about the anxiety of the first lines of “I cannot live with Youâ” is that that anxiety stems not only from the distance that separates “I” from “You” but from the consequences of the apostrophe that separation invokes. While “I think To Liveâ” defers its apostrophe until its last word (so that, in effect, the apostrophe cannot become what de Man would identify as the personal abstraction of a prosopopoeia, cannot attribute to “Thee” a face, a figure), “I cannot live with Youâ” begins with the problem of keeping “You” in the Real, outside its own apostrophe's reach. That reach, as the lines demonstrate at length (at fifty lines, this is one of Dickinson's longest published poems) is extensive: it encompasses this life, death, afterlife, heaven, hell, memory, the self:

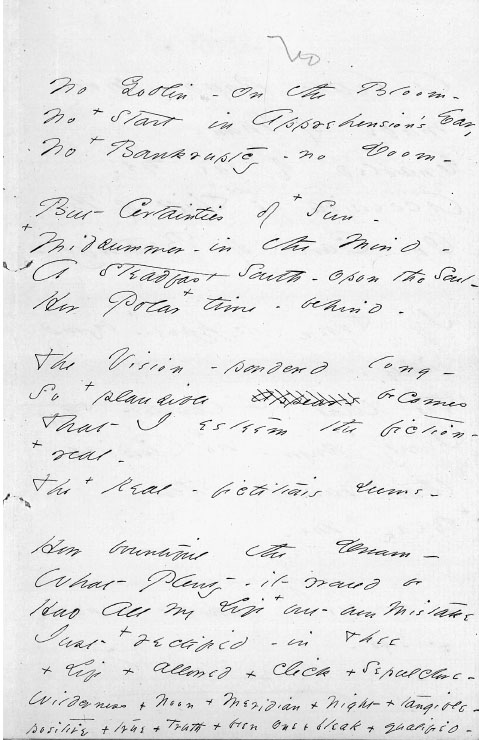

Figure 22a and 22b. Emily Dickinson, about 1867. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 357).

I could not dieâwith Youâ

For One must wait

To shut the Other's Gaze downâ

Youâcould notâ

And IâCould I stand by

And see Youâfreeze-

Without my Right of Frostâ

Death's privilege?

Nor could I riseâwith Youâ

Because Your Face

Would put out Jesus'â

That New Grace

Glow plainâand foreign

On my homesick Eyeâ

Except that You than He

Shone closer byâ

They'd judge UsâHowâ

For Youâserved HeavenâYou know,

Or sought toâ

I could notâ

Because You saturated Sightâ

And I had no more Eyes

For sordid

x

excellence

x

consequence

As Paradise

As Cameron suggests, this “catechism is one of renunciation,” but it is important to notice that what is renounced at each stage of this catechism is a face-to-face encounter with “You” (LT 78). In other words, what is renounced is the performative affect of apostrophe, the trope that brings “You” into the moment of speech. In the fourth and fifth stanzas, that renunciation turns on the moment of death (as “I could not dieâwith Youâ” follows almost by catechistic rote upon the first line, save for the graphic stutter of the em dash), or the moment a nineteenth-century reader would recognize as the death vigil. Whether one shuts “the Other's Gaze downâ” or “⦠I stand by / And see Youâfreezeâ” the emphasis is on envisioning an encounter that the lines do not want to envision, not only because doing so would be an admission of mortality but because seeing the other's face would mean turning “You” into a fiction. That fiction would allow address to transcend the material circumstances of separation, as the abrupt and seamless transition from physical death to life after death insists. If the lines were to admit such transcendence (and this is, after all, the historical moment of Elizabeth Phelps's

The Gates Ajar

, the popular novel in which reunion after death is carried on in vivid, even domestic detail, and to which the last stanza may contain an allusion), “Your Face / Would put out Jesus'.”

47

But by not imagining its own apostrophe as transcendent, the lines do not give a “Face” to “You”; what they do instead is to tally the consequences as if they were to do so.