Dickinson's Misery (13 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

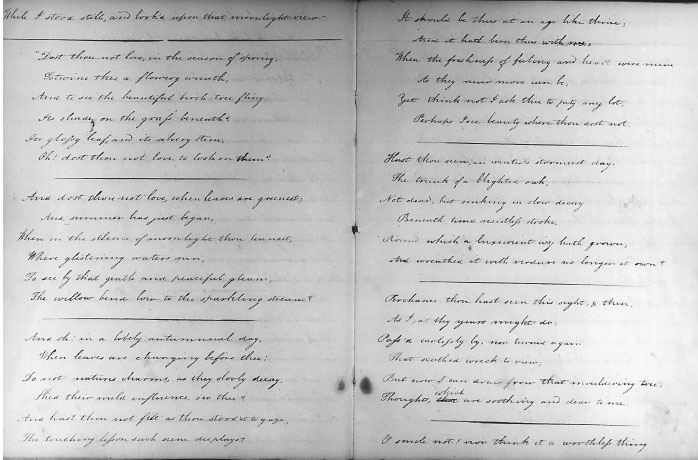

Figure 10. Page family notebook, 1823â27. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

As we shall see in the chapters that follow, Dickinson's use of commercial advertisements, pasted clippings, other people's poems, bits of fabric, dead insects, pressed flowers, accidental blots, and collections of her own lines as companions for her writing not only expand that writing's field of reference but should expand our notion of the genre on which her lines so often comment. In the next chapter, I will consider the developments in twentieth-century lyric theory that make it so difficult for us to compass that expansion in our idea of the lyric itself. But before we move on to the century of theoretical speculation on the lyric that would accompany the expanding circulation of Dickinson's lyrics in and beyond print, one final example from the archive that might stop such speculation in its fossil bird-tracks is in order. Perhaps just before she wrote the lines on the split-open envelope (

fig. 5

) that begin “When what / they sung for / is undoneâ,” Dickinson wrote a related series of lines that survive in four different manuscript versions. Three of the manuscripts were sent to familiar correspondents: Frances Norcross, Dickinson's cousin, made a transcript of a version sent to her, a version in pencil was sent to Dickinson's friend Sarah Tuckerman at around the same time, and on May 12, 1879, Helen Hunt Jackson wrote to Dickinson: “I know your “Blue bird” by heartâand that is more than I do any of my own verses.âI also want your permission to send it to Col. Higginson to read. These two things are my testimonial to its merit.”

61

Clearly Jackson, maven of print circulation that she was, thought of the manuscript Dickinson sent to her as a lyric that could be detached from its address to her and circulated to other readersânotably, to a reader to whom Dickinson also sent many poems, the man who would edit and inaugurate the poems' public circulation as individual

lyrics. And clearly, by sending versions of the same manuscript to several persons, Dickinson herself indicated that the lines were not intended for one readerâas, say, a personal letter might beâbut could circulate independently of particular readers or a particular material context. Though this sociable exchange of verse does not approach the anonymous circulation characteristic of the print public sphere, it does represent an increasing detachment of the text from its conditions of circulation. Why not, then, just print and interpret the lines as an independent lyric?

The lines have indeed been just so printed and interpreted since Higginson and Todd edited the 1891

Poems.

Franklin's most recent printed version renders them as Poem 1484:

Before you thought of Spring

Except as a Surmise

You seeâGod bless his Suddennessâ

A Fellow in the Skies

Of independent Hues

A little weather worn

Inspiriting habiliments

Of Indigo and Brownâ

With specimens of song

As if for you to chooseâ

Discretion in the intervalâ

With gay delays he goes

To some superior Tree

Without a single Leaf

And shouts for joy to nobody

But his seraphic Selfâ

The lines are directly addressed, but since we know that each of at least three different people thought that she was the unique addressee (thus Jackson's request for Dickinson's permission) and was not, we might conclude that they are not addressed as historical but as fictive discourse. As Barbara Herrnstein Smith has usefully defined the distinction, when we interpret an historical or “natural” utterance, “we usually seek to determine its historical determinants, the context that did in fact occasion its occurrence and formâ¦. The context of a fictive utterance, however, is understood to be

historically indeterminate.

”

62

By this logic, once we decide that Franklin's Poem 1484 was not a Dickinson letter but a Dickinson poemâthat is, once we decide on the text's genreâthen the circumstances of its original circulation and composition matter less than our interpretation of the text itself. Once we decide that a text is “historically indeterminate” and therefore fictive, we infer that the text asks us to make of it what

we will. Indeed, as we have begun to see, such moments of what Dickinson's lines call “Discretion in the intervalâ” characterize the history of the lyricization of Dickinson's writing. But whose “Discretion” is it? In what is now Poem 1484, the bird that sings to himself is Mill's perfect figure of the actor who acts well because he takes no notice of his audience. Yet the difference between Dickinson's bird and Mill's actor is that Dickinson's “you” is the one who puts the bird on stage. Your interpretation of the timely announcement of spring as a performance intended for you is a mistake: though you may experience the “specimens of song / As if for you to chooseâ,” that

as if

makes all the difference. Your mistake is a fiction that you enjoy, and since the bird is unconscious of it, you might as well. The lines that begin “When what / they sung for / is undone” may worry about the afterlife of lyricism, but the lines that begin “Before you thought of Spring” do not.

63

Why should we?

In the chapters that follow, I will not continue to worry about whether or not Dickinson wrote lyric poems. I shall leave that up to you. What I will explore instead are Dickinson's intricate uses of lyricism in her writing, and the ways in which her writing has come to exemplify assumptions about lyric interpretation. As we shall see, some of those assumptions have nothing to do with the texts published as Dickinson's lyrics, some of them do, and some of them are just historically inappropriate. But all of the genre mistakes associated with Dickinson's writing are instructiveâand all of them lead us further and further away from a conclusion about how Dickinson's work

should

be edited, either in print, in facsimile, or as an electronic archive. The fact remains that Dickinson's private composition and circulation of her writing makes that writing exemplary of the lyric in modernity

and

exemplary of how far modern forms of acontextual lyric reading miss its mark.

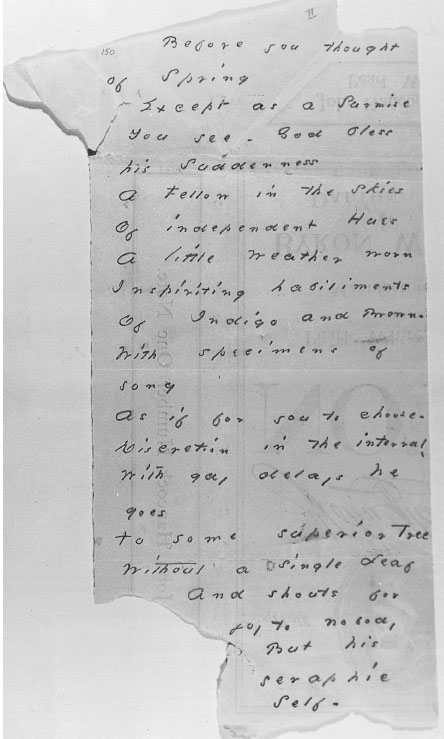

The fourth extant manuscript version of the lines that begin “Before you thought of Spring” were written on the back of a wrapper for John Hancock writing paper (

figs. 11a

,

11b

). As you can see, Dickinson wrote “Blue Bird” on the printed side advertising the hot-pressed paper inside the wrapper. Whether the inscription represents her answer to the lines' riddle or the title of her poem we cannot say. If the words are a title, then this is one of the few instances in which Dickinson actually titled one of her own poemsâan instance that would suggest that she thought of her writing as a set of discrete lyrics.

64

And now that the wrapper is itself printed (for the first time) here, next to the lines known for over a century as a Dickinson poem, you will also notice that as evidence of Dickinson's authorial title or signature, it bears her “John Hancock.” You may also notice that once that name comes to suggest a pun, then “Byron” is also a poet's name, and the “Number One Note” that the bird on the verso side utters may be

literalized on the printed side of the pageâso literalized that it has been stamped in small print, “Copyright Secured.” Of course, while you are imagining these associations, you will realize that you are merely reading a found page lyrically; the maker of the wrapper certainly did not intend for you to interpret those signs in that way, in the fictive discourse of that genre. Like the bird who sings “to nobody,” the wrapper is just advertising paper. Yet now that the wrapper has been published as part of a Dickinson poem, associations between literal accident and figurative meaning invite surmise. What you have just done is what I call “lyric reading,” and it is a double bind. In the next chapter, we will explore some coincidences between literal reference and figurative meaning in the verse Dickinson circulated to her familiar correspondents, and then we will turn to later versions of lyric reading that took poems out of such contingent relations and so made everything that was not a lyric disappear.

Figure 11a. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 150).

Figure 11b. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. 150, verso).

Lyric Reading

“M

Y

C

RICKET

”

I

N THE ISSUE

of the

Springfield Republican

for March 23, 1864, a small notice announced that

In Flatbush, N.Y., last Sunday, William Cutter, a farm laborer, attempted to shoot Anne Walker, a servant in Judge Vanderbilt's family. He fired twice, one of the balls passing through her sleeve and the other lodging in her hip. Cutter also shot at Mrs. Vanderbilt, who ran to the assistance of the girl, inflicting a very severe, and probably mortal wound in the abdomen. Cutter's attentions to Miss Walker had been discarded by her, and hence his attempt at revenge.

1

The account was reprinted from the

Brooklyn Eagle;

Samuel Bowles, the editor of the

Springfield Republican,

forwarded the

Eagle

article to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, commenting that “it is all horrible, & tears, & tortures, & sets all fundamental ideas afloat.” Vanderbilt was Susan Dickinson's friend from school, and the interest of her personal connection to the victim was enhanced when the incident became a public eventâso public that when Vanderbilt survived, Henry Ward Beecher reportedly called her the “visible evidence of spiritual life.”

2

In September 1864, Emily Dickinson wrote to Susan, “I am glad Mrs.âGertrudeâlivedâI believed she wouldâThose that are worthy of Life are of Miracle, for Life is Miracle, and Death, as harmless as a Bee, except to those who runâ” (L 2:294).

To Gertrude Vanderbilt herself, whom she had never met, Dickinson addressed several lines. She may have sent verses to Vanderbilt because of Vanderbilt's friendship with Susan Dickinson, or perhaps because through that connection three Dickinson poems had just appeared in the

Drum Beat,

a paper published during the two weeks of a fund-raising fair sponsored by the Brooklyn and Long Island Fair for the Benefit of the U. S. Sanitary Commission (to improve conditions for Union troops).

3

In making transcripts in 1891 of the lines sent to Vanderbilt, Mabel Loomis Todd echoed Vanderbilt's private involvement in public matters when she noted that they were “to Mrs. Vanderbilt, after she had met with a serious accident at the close of the warâ.”

4

Todd's confusion of private and public events, accident and intention foretold the fate of Dickinson's letters to

Susan's Brooklyn friend: the four of which Todd made transcripts were all published as poems over the next sixty years.

5

Two of the letters seem to refer directly to Vanderbilt's “serious accident” and recovery. One of them was published as a letter in 1894, 1924, and 1931, and then as a poem in 1955 (J 830):

6