Dickinson's Misery (15 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

That incongruity would have been important in the United States in 1864 and 1865. We need only recall once again that most popular of Union Civil War poems, “The Battle-Hymn of the Republic,” to see that “[w]hile God is marching on” in Howe's call to arms, “trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored,” the apostrophe to the “sacrament of summer days” in Dickinson's

Drum Beat

poem does not suppose that those days' “immortal wine” is anything but an autumnal illusion. Now, since the lines appear to have been first sent to Susan Dickinson in the 1850s, it is unlikely that Dickinson originally intended them to resonate with the discourse that intensified with the war; it was only their accidental publication in 1864 in a paper devoted to the Union cause that made the untimely “sacrament of summer days” potentially analogous to a divinely sanctioned ray of hope in a darkening season.

16

And if the beginning of the last year of the war was a hybrid season, then the summer after the end of the war was a season of stark contrasts. The immense relief that the war was over was followed so swiftly by Lincoln's assassination and the registration of such enormous national loss (including the loss of the identity of “the nation” itself) that, as Louis Menand has written, martial victory seemed to have come at the cost of “a failure of culture, a failure of ideas.”

17

If Dickinson did send the lines that begin “Further in Summer than the Birds” to Vanderbilt in the summer of 1865, then the “Minor Nation” of crickets observes an Old World Catholic “Custom” unavailable to the ravaged modern Protestant culture of Dickinson's place and time.

18

Unlike the suffering modern American postwar nation, the pathos of the crickets' “Minor Nation” finds coherent cultural expression; their natural ceremonies may be invisible, and they

may not be metrical, but the last lines describe them in the rhetoric of classic nationalism (“⦠for Her Land ⦠for Her Sea ⦔) as the Earth's “Elegy.” Yet while the elegy is apt, the sacramental language used to describe it is evidently not: is “a Minor Nation” a nation at all? Is an “Ordinance” that cannot be “seen” still a rite or statute? Is a “pensive Custom” no longer a custom because no longer ingrained habit? Is a “Tune” without “Cadence” or “Pause” a song?

Those questions may be rhetorical, but the last lines sent to Vanderbilt, beginning “The Earth has many / keys,” appear to reverse their direction, or put them to rest. In these lines, human “Melody” cannot be imposed on nature, which is suddenly (and strangely, after having been made into a Catholic nation with its own customs) “the Unknownâ / Peninsulaâ.” As Joanne Feit Diehl has pointed out, Dickinson's lines may echo Keats's sonnet “On the Grasshopper and the Cricket” and its opening assertion that “[t]he Poetry of the earth is never dead.”

19

If so, however, then unlike Keats's cricket by the hearth, Dickinson's cricket does not sing of nature's persistence within culture but of a natural death that culture cannot repair. That reversal of the first lines' emphasis might be why Bingham printed them separately as Poem 139 (Johnson followed suit in 1955 and made “The earth has many keys” the last poem in his collection, Poem 1775, an error that led several later interpreters to treat the poem invented by a modern editor as Dickinson's own last poem).

Now, the cricket's elegy may be or may have been simply the elegy of summer's passing, and its elevated or outlandish description no more than that. Yet the summer of 1865 was full of elegies for nature that were elegies for the culture lost with Lincoln and the war. Whitman's great pastoral elegy “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd” may now be the best known of such poems, a spring elegy on the occasion of the events of April 1865, and the most beautiful lines ever written on the relation between seasonal redemption, Christian myths of resurrection, and cultural reformation. Yet there were many less distinguished elegies published that summer in the aftermath of the war. In the July 1865 issue of the

Atlantic Monthly

a sonnet appeared, bearing a somewhat out-of-date title:

ACCOMPLICES.

Virginia, 1865.

The soft new grass is creeping o'er the graves

By the Potomac: and the crisp ground-flower

Lifts its blue cup to catch the passing shower;

The pine-cone ripens, and the long moss waves

Its tangled gonfalons above our braves.

Hark, what a burst of music from yon wood!

The Southern nightingale, above its brood,

In its melodious summer madness raves.

Ah, with what delicate touches of her hand.

With what sweet voices, Nature seeks to screen

The awful Crime of this distracted Land.â

Sets her birds singing, while she spreads her green

Mantle of velvet where the Murdered lie,

As if to hide the horror from God's eye!

20

The war over, “accomplices” seems the wrong word for the signs of natural recovery the sonnet describes. Yet, as becomes (all too) clear in the closing sestet, the grass, flowers, moss, and birds of postwar Virginia are in cohoots with the Union's former enemies by themselves regenerating a pastoral scene to “screen” the war's casualties. “The Murdered” appear all the more murdered (as opposed to, say,

fallen

in battle) in contrast to the apparent peace of the pastoral scene.

21

Not the instruments of divine will (like Howe's “grapes of wrath”) but attempts “to hide the horror from God's eye” (still identified with the wounded Union's perspective), the sonnet mourns the fact that natural expression is not cultural expressionâor if it is, it is the expression of the wrong culture, the wrong poetry of the wrong earth. “The Southern nightingale” could not exist in nature in North America, but as romantic poetic figure it becomes the laureate of “this distracted Land,” a rough analogy to the cricket's function as “Witness for Her / Land” in Dickinson's lines. Unlike “The Earth” in “Further in Summer than the Birds,” however, Virginia in 1865 was, according to the sonnet, still removed and led astray from the Union, a condition that nature could not repair. The problem in the

Atlantic

sonnet is that nature is not naturally elegiac; “its melodious summer madness” is the wrong tune for the cultural season, or for what will now, the poem suggests, count as the perspective empowered by the state to decide that the South's actions were criminal.

The perspective of the sonnet itself is not hard to locate: as a rather elaborate combination of Italian and Elizabethan forms in Wordsworth's modern mode (including couplets within as well as at the end of the sonnet), the poem claims the privilege of its high-middlebrow

Atlantic

publication (a rough equivalent to the contemporary weekly

New Yorker

poems) to present what later in the century in another genre the same magazine would call “local color.” In contrast, in Dickinson's 1865 lines to Vanderbilt, “Beauty is Nature's / Fact” rather than the sign of individual or cultural pathos, though “the Cricket” can still seem the “utmost of Elegy, to Meâ.”

22

That last prepositional phrase, signed “Emily” in the original

manuscript, qualifies the problem of whether nature actually mourns and makes it a matter of personal, rather than cultural, perspective. The question is then how that personal perspective circulates, of what forms it takes, of what culture it may create.

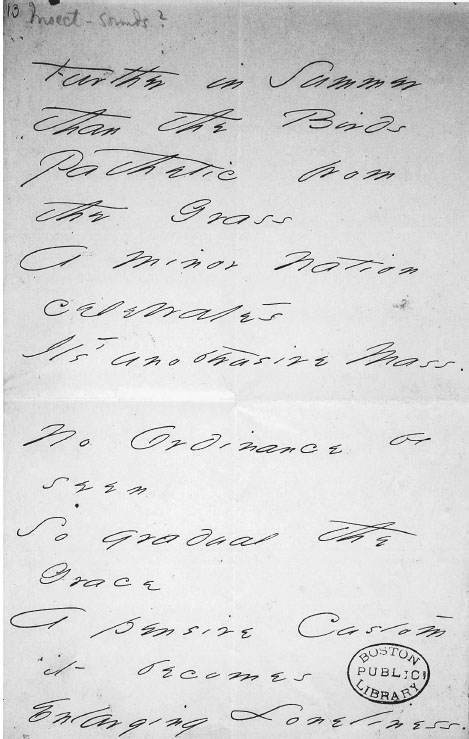

We do not have a record of Vanderbilt's reply to Dickinson's “Further in Summer than the Birds,” if she wrote one. We do know that Dickinson sent a similar set of lines to her cousins, Louise and Frances Norcross, perhaps also in 1865, but that manuscript has been lost. In 1866, Dickinson sent some of the same lines to Higginson (

figs. 14a

,

14b

), accompanied by a note:

Carlo, Dickinson's Newfoundland dog, would have been about sixteen years old in 1866.

24

Since her first letter to him in 1862, Dickinson had been asking Higginson for “instruction” in writing, so perhaps she meant to present her lines as evidence of her attempt to write an elegy. But an elegy for what, or for whom? If Vanderbilt might have understood the lines sent to her in 1865 in the context of the aftermath of the war, did Higginson understand them as an elegy for a dog? In the version of the lines sent to Higginson, neither the invocation of national witness in the final lines to Vanderbilt nor the word “elegy” appears:

Further in Summer

than the Birds

Pathetic from

the Grass

A minor nation

celebrates

It's unobtrusive Mass.

No Ordinance be

seen

So gradual the

Grace

A pensive Custom

it becomes

Enlarging Loneliness.

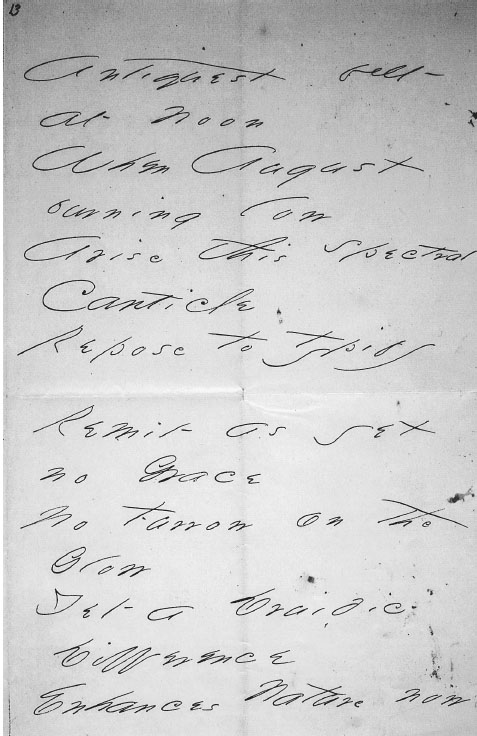

Antiquest felt

at noon

When August

burning low

Arise the spectral

Canticle

Repose to typify

Remit as yet

no Grace

No Furrow on the

Glow

Yet a Druidic

Difference

Enhances Nature now[.]

Figure 14a. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1866. Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department, Courtesy of the Trustees (Ms. AM 1093, 22).

Figure 14b. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1866. Boston Public Libaray/Rare Books Department, Courtesy of the Trustees (Ms. AM 1093, 22).

Since Dickinson sent the lines to Higginson in late January 1866, they certainly did not refer to a current natural season, and if they may have resonated with a cultural season in the summer of 1865, then that resonance must have been fainter in the winter of 1866. Dickinson's rather abrupt note to Higginson at the beginning of 1866 was actually the first letter she had sent to him since she had written to him in early June 1864, after learning that he had been wounded in battle in July 1863 and had left the Union army in May 1864.

25

Dickinson herself was in Cambridge under the care of a doctor for eye trouble in 1864; she had written to Higginson to ask if he were “in danger,” commenting that “Carlo did not come, because he would die, in Jail” (L 290). Thus the letter of 1866 picks up the thread of the dog's health, but may also continue the oblique reference to the consequences of the war. The lines to Higginson that differ from those in the letter to Vanderbilt not only take out the earlier explicit reference to “elegy” but place the consequences of seasonal change earlier and further within the discourse of natural sympathy than did the lines to Vanderbilt. The first new line, “Antiquest felt,” puns on the Old World “Mass” and “Ordinance,” but shifts the language of outmoded “Custom” to the realm of individual sensibility, and that shift also changes what the ritual of the crickets is said to “typify.” The symbolic function of cricket song has moved away from the register of natural national “witness” in the lines to Vanderbilt; in the lines to Higginson, the still vaguely Catholic “Canticle” represents midday “Repose.” But whose repose? The abstraction of the lines to Higginson align the day's apex with individual pathos and then align both with an even older, more culturally misplaced religious rite, a “Druidic / Difference.” The lines are certainly more abstract than were the lines sent to Vanderbilt, but the relation between natural and cultural expressionâor the problem of what form expression should takeâhas become more acute.

If that problem may have attached itself to the historical climate in the seasons just after the war, or even to the death of Carlo in 1866, it would

have presented itself very differently seventeen years later when Dickinson sent the lines she had sent to Higginson to Thomas Niles. Niles was the chief editor at Roberts Brothers, the publisher that would issue the first volumes of Dickinson's poems in the 1890s. He had initiated a correspondence with Dickinson in 1878, after he had published a Dickinson poem in the anonymous collection

A Masque of Poets.

26

In 1883, Dickinson wrote to thank him for a copy of the Roberts Brothers' edition of Mathilde Blind's

Life of George Eliot,

writing, “I bring you a chill GiftâMy Cricket and the Snow” (L 813). She then included the lines she had sent to Higginson in 1866 in the letter before her signature (

figs. 15a

,

15b

,

15c

), and separately enclosed the lines that became “It sifts from Leaden Sievesâ” (F 291). Though Niles apparently addressed Dickinson several times, asking for “a M.S. collection of your poems, that is, if you want to give them to the world through the medium of a publisher” (L 813b), she sent only what she called such “gifts,” naming them as if they were the objects they described: “My Cricket and the Snow,” or “the Bird ⦠a Thunderstormâa Humming Bird ⦠a Country Burial” (L 814). Dickinson's objectification of her writing mirrored her own practice of including objects with or within the writing; like the pressed flowers, dead insects, assorted clippings, or illustrations that often accompanied the lines she addressed to particular correspondents, the “gifts” sent to Niles were marked by the singular rather than the commodity formâor at least that is the way Niles himself seems to have understood Dickinson's intention. “I am very much obliged to you for the three poems which I have read & reread with great pleasure,” he wrote to Dickinson in 1883, “but which I have not consumed. I shall keep them unless you order me to do otherwiseâ” (L 814a). The intimacy supposed by the exchange of the singular object obliges its recipient to keep it, and his relationship to the giver, to himself.

27

But we know that the verse Dickinson referred to as “My Cricket” was not a singular objectâon the contrary, it was a text she had circulated to various correspondents over the course of over sixteen years. By sending it to Niles, a publisher she would never meet, did she not intend to widen those conditions of circulation, to go public? If the difference between a singular object and a commodity is the exchange value of that object, then we would have to say that by sending her verse to Niles, Dickinson was potentially increasing the exchange value of her writing, or bringing it closer to the commodity form.

28