Dickinson's Misery (14 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

To this World she returned

But with a tinge of thatâ

A Compound manner,

As a Sod

Espoused a Violet,

That chiefer to the Skies

Than to Himself, allied,

Dwelt hesitating, half of Dustâ

And half of Day, the Bride.

Emily

Another has never been published as a letter, and was first published as a poem in 1945 (BM 193):

Dyingâto be afraid of Theeâ

One must to thine Artillery

Have left exposed a friendâ

Than thine old Arrow is a Shot

Delivered straighter to the Heart

The leaving Love behindâ

Not for itself, the Dust is shy.

ButâEnemyâBeloved beâ

Thy Batteries divorceâ

Fight sternly in a dying eye

Two Armies, Love and Certainty,

And Love and the Reverseâ

Emily

Dickinson then copied both sets of lines onto the sort of bifolium sheets she had formerly bound in the fascicles, but after 1865 apparently arranged without binding.

7

Did the copies of the letters no longer refer to Vanderbilt? Were they ever specifically addressed to Vanderbilt? Once lifted out of the fabric of personal and public sociability in which they were originally embeddedâaway from Vanderbilt as cause célèbre, from the scandal of the rich white woman's dangerous employees, from Vanderbilt's implication in the war and related social causes, from Susan's friendship with her, from Dickinson's presumption of intimacy with Vanderbilt (though not with her servant) through her intimacy with Susan,

from Bowles's familiar address to Susan and his editorial and personal involvement with the Dickinsons (especially Emily), from the way friends made their way into newspapers and newspapers made their way into homes, from the coincidence between the war and Vanderbilt's “accident”âthe lines no longer seem to refer to an historical occasion. Without the signature, and printed as they now appear in Franklin's edition, they look like lyric poems.

As I suggested in the previous chapter, whatever the lines

were

before they were collected and published, their existence in modern volumes may mean that the lines now

are

lyricsâat least for the purposes of interpretation. In this chapter, I will consider one of the most curious purposes of lyric interpretation during the period in which Dickinson's poems have appeared in print: a great deal of lyric reading in the twentieth century attempted to restore lyrics to the social or historical resonance that the circulation of lyrics as such tends to suppress. And since, from the perspective of modernity, that interpretation is always a recovery project, the resonance that reading restores to lyricsâespecially to Dickinson's lyricsâtends toward pathos. Thus when some of the lines that begin “Dyingâto be afraid of Theeâ” became Poem 831 in Johnson's 1955 edition of Dickinson's

Poems

, Shira Wolosky could write in 1984 that in the poem, martial “conflict becomes an image of Dickinson's inner strife concerning an afterworld,” and so conclude that Dickinson's poetry was not just “private and personal” but engaged in the suffering and dilemmas that characterized (Northern) intellectual life during the Civil War.

8

If one begins with the poem in print and if one assumes that a poem is the visible evidence of inner life, then it does seem as if the “Artillery,” the “Shot, the “Batteries,” and the “Armies” are figures borrowed from the period's literal strife as vehicles of personal expression. Yet if one begins with the Vanderbilt incident, Dickinson's expression may seem no less personal, though its vehicles will seem less figurative. Dickinson's language may aggrandize domestic violence into political and metaphysical contest, but such exaggeration is part of the point of the letter to Vanderbiltâit makes explicit the associations that Bowles and Beecher and Todd all implied. Yet once the letter becomes a lyric, and once the lyric is printed and opened to lyric reading, those public and private associations and their literal and figurative certainties are reversed.

Versions of the other two letters to Vanderbilt take up the confusion between literal reference and lyric reading even more explicitlyâand, as we shall see in this chapter, in ways that are telling for the history of lyric interpretation in the United States in the last century. The ambitious modern theories of the lyric that emerged in the twentieth century may be far removed from the circumstances of Dickinson's writing, and far removed

from (if implicit in) most practical criticism of Dickinson, but they all, in different ways, took up the problem of the lyric's removal from modern culture; to return to Grossman's phrase in

Summa Lyrica

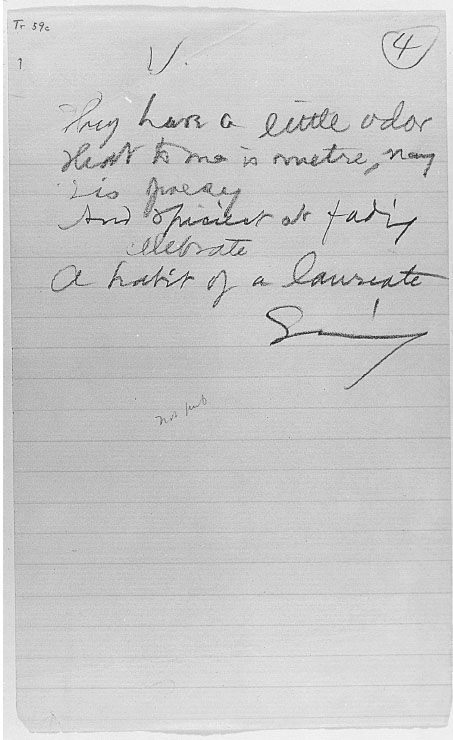

, they all aimed to construct “a culture in which poetry is intelligible” (207). The assumption behind such theoretical construction is always that we no longer live in such a culture. But Dickinson did. In another note sent to Vanderbilt, of which only Todd's transcript survives (

fig. 12

), the verse was “intelligible” to its addressee precisely because its literal referent was enclosed in the envelope:

They have a little odor

That to me is metre, nay 'tis poesy

And spiciest at fading celebrate

A habit of a laureate.

(F 505)

9

If Vanderbilt understood the wit of the lines in relation to an enclosed bouquet from Dickinson's garden or conservatory, then how do we understand the lines without the enclosure? Dickinson herself opened the question when she copied the lines into a fascicle (

fig. 13

), though of course if the fascicles were personal collections, she would have known the original referent.

10

Millicent Todd Bingham was the first to publish the lines as verse in 1945 in her book defending her mother's editorial work on the Dickinson manuscripts, though it is perhaps significant that she used them as an epigraph to a chapter entitled “Creative Editing.”

11

We could decide that the exact referent for the pronoun makes no differenceâthat when printed as Poem 88 in

Bolts of Melody

or Johnson's Poem 785 or Franklin's Poem 505, the point of the lines is that “metre” and “poesy” (or “melody”) are metaphors. But they only become metaphors when they are no longer puns on the relation between flowers and poems, a relation that, as Vanderbilt and Dickinson and any other nineteenth-century reader would know, usually worked the other way around (so that “flowers” would be a term used to refer to poems rather than “poems” becoming a term one uses to refer to flowers).

12

If comparisons between Dickinson's printed lyrics and their manuscript forms merely continued to yield reversals of literal and figural fortune, they would be worth making, but they would not be very suggestive for a theory of modern lyric reading. Yet several versions of the lines in the fourth letter to Vanderbilt suggest much more than such a reversal: the history of their familiar circulation as well as the history of their publication and later reception open into the central issues in twentieth-century lyric theoryâindeed, the story of their transmission exemplifies the emergence of the lyric as a creature of modern interpretation and its shift toward personal and cultural abstraction. That story began rather modestly when, in the summer of 1865, Dickinson sent some of the most beautiful lines she ever wrote to Flatbush:

Figure 12. Mabel Loomis Todd's transcript of the note to Gertrude Vanderbilt that is now Franklin's poem 505. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. Tr. 59c).

Figure 13. “Fascicle” copy of lines in

fig. 12

, lower half of page. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. No. 81-9, verso).

Further in Summer than

the BirdsâPathetic from the

Grassâa Minor Nation

celebrates it's unobtrusive Massâ

No Ordinance be seenâ

So gradual the Grace

A pensive Custom it

becomes Enlarging lonelinessâ

'Tis Audiblest, at Duskâ

When Day's attempt

is done and Nature nothing

waits to do but terminate in Tuneâ

Nor difference it knows

Of Cadence, or of

Pauseâbut simultaneous as

Sameâthe Service emphasizeâ

Nor know I when it

ceaseâ

At Candles, it is hereâ

When Sunrise isâthat

it is notâthan this, I know

no moreâThe Earth has many

keys where Melody is not

Is the Unknownâ

PeninsulaâBeauty is Nature's

Factâbut Witness for Her

Land and Witness for Her

Seaâthe Cricket is Her

utmost of Elegy, to Meâ

13

If, as I suggested in the last chapter, birdsong represented for Dickinson and for the period as a whole a lyricism unattainable by the human poet, then we might say that the cricket's song is even “further” removed from the capacity of human expression than is the nightingale's or skylark's or bluebird's. By this logic, the crickets can express what the writer cannot, or can, as part of nature, themselves become the signs of seasonal wane, of summer's passing. Thus these lines, unlike the lines in the other letters to Vanderbilt, do not seem to refer to any historical circumstance or literal enclosure known to the two women. On the contrary, their theme of seasonal

change as well as their use of the cricket as poetic figure place them squarely in the abstract temporality and figurative referentiality of the lyric.

Or so it now seems to us. As it happened, another set of lines that were published in the

Drum Beat

twelve days before Vanderbilt was shot bear a relation to the lines now known to most readers of Dickinson's poems as “Further in Summer than the Birds.” In the first edition of Dickinson's

Poems

in 1890, Higginson and Todd gave the following lines the title “Indian Summer,” though they were entitled “October” in the final issue of the

Drum Beat

issued on March 11, 1864:

These are the days when birds come back,

A very few, a bird or two,

To take a backward look.

These are the days when skies resume

The old, old sophistries of June,â

A blue and gold mistake.

Oh, fraud that cannot cheat the bee!

Almost thy plausibility

Induces my belief,

Till ranks of seeds their witness bear,

And softly, through the altered air,

Hurries a timid leaf.

Oh, sacrament of summer days,

Oh last communion in the haze,

Permit a child to join!

Thy sacred emblems to partake,

Thy consecrated bread to take,

And thine immortal wine!

(F 122 [B])

Whether or not Vanderbilt was responsible for the

Drum Beat

publication of Dickinson's poems, both she and Dickinson would have read the poem reprinted above in that paper.

14

If Dandurand and Franklin are right that the lines that begin “Further in Summer than the Birds” were sent to Vanderbilt late in the summer of 1865, then they would have been written over a year after the lines about late season birds were published in 1864. Like the crickets in the later lines, the birds in the lines that appeared in the Brooklyn paper are signs of changeâthough the fall birds are misleading, seeming to signal summer rather than winter. What is striking when one

puts the lines next to one another (something no editor of Dickinson has done) is the somewhat inappropriate language of Christian ritual that characterizes both sets. The language is “somewhat inappropriate” in the sense that in the

Drum Beat

poem, what is frankly called a “mistake” in the sixth line becomes a “sacrament of summer days” in the thirteenth; in the lines that begin “Further in Summer than the Birds,” the “unobtrusive Mass” celebrated by the “Minor Nation” of Crickets is a strangely elaborate figure for cricket song. In both the poem published in the

Drum Beat

and in the lines sent to Vanderbilt in 1865, the activities of birds and crickets are described as highly ritualized Christian observanceâso highly ritualized that they seem absurd activities for even anthropomorphized birds or crickets.

15

If in the romantic lyric birdsong was (and it was) a figure for the native culture of nature, in Dickinson's lines birds and crickets clearly do not belong to the culture of “sacrament,” “communion, “Mass,” and “Ordinance” used to describe them. Dickinson's lines place Christianity, cultural iconography, nature, and writing at odd angles to one another.