Dickinson's Misery (8 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

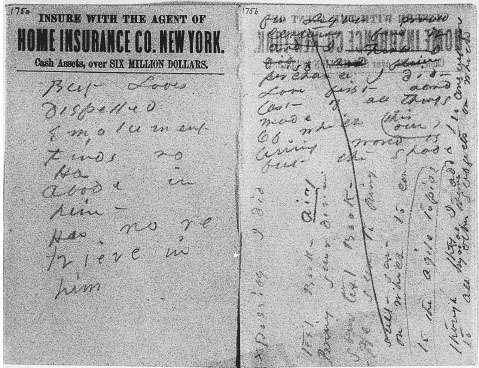

The first lines to be published from the many odd lines running along the sheets at odd angles in

figures 7a

and

7b

were, oddly enough, taken from the center of the least legible, most heterogeneous page; they were printed by Bingham in 1945 in a section simply entitled “Fragments”:

627

Love first and last of all things made

Of which our living world is just the shade.

(BM 317)

The more legible set of lines on the front of the sheets was then published by Bingham in an essay on the “Prose Fragments of Emily Dickinson” in 1955âseventy years after the memo pages were found in the locked box.

20

In their first appearance in print, these lines were cast not as a poem but as what Bingham described as “successive attempts to overtake an idea” in prose. Johnson followed Bingham by printing the recto lines in the section of “Prose Fragments” in his 1958 Letters (L 915) and went on to publish the verso lines not as a poem but as another prose fragment, though he points out that the lines that Bingham had already published as a verse fragment “recall the Prelude to Swinburne's âTristram of Lyonesse,' which opens: âLove, that is first and last of all things made, / The light that has the living world for shade” (L 917â18). Although no longer printed as a poem, by 1958 a poem had been recognized in Dickinson's linesâthough it was not a poem first written by Dickinson, and it was notâat least in Swinburne's contextâa lyric. Thirty-five years later, in 1993, William H. Shurr published

New Poems of Emily Dickinson

, a glossy volume that claims to recover “the prose-formatted poems” that have remained hidden in Dickinson's prose.

21

Shurr accepts Bingham's and Johnson's characterizations of most of the

HOME INSURANCE CO. NEW YORK

pages as “one of [Dickinson's] prose fragments,” but suggests that this fragment in prose contains “an overlooked workshop poem in which Dickinson has not yet decided between two alternate lines to give the final shape to a thoughtful quatrain:

Figure 7b. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss. 175, 175a).

486

Eternity may imitate

The Affluence (Ecstasy) of time

But that arrested (suspended) syllable

is wealthier than him

But Loves dispelled Emolument

Finds (Has) no Abode in himâ

(Has no retrieve in him).”

22

By 1993, then, a poem not attributable to another poet had finally been recognized in Dickinson's lines; it had been over a hundred years, but as Bingham eloquently described the moment of recognizing the genre one had already decided was immanent, “after laboriously puzzling out a word, a line, a stanza, letter by letter, with all the alternatives, one is rewarded by seeing, suddenly, a perfect poem burst full-blown into life” (BM xv). But whose poem (and whose life) is it? When did it become a poem? And where is the poemâon Dickinson's memo page or on the “new” printed ones?

In the 1998 variorum, Franklin followed Shurr by printing as his Poem 1660 a quatrain drawn from the recto lines in

figures 7a

and

7b

, but he departed from Shurr by giving final shape to a

different

quatrain, which appears alone in his 1999 reading edition:

But that defeated accent

Is louder now than him

Eternity may imitate

The Affluence of time.

(FR 1660)

In his variorum edition, Franklin dates the manuscript “about 1884” and notes that “also present is a prose draft beginning âPossibly I did' that includes a quotation from Swinburne” (F, note to 1660). He then goes on to print the lines that follow the first four lines on the recto pages as variants of his printed quatrain. In order to make the point that they are variants and not independent prose or verse lines, Franklin reprints in brackets what he takes to be the precedent lines for which Dickinson sketched several possible endings, which he separates with printer's bullets:

But that suspended syllableâ

Is wealthier than him

â¢

But that] arrested [syllableâ]

Is wealthier than him]

â¢

But Love's dispelled Emolument

Finds no Abode in himâ

â¢

But Love's dispelled Emolument]

Has [no Abode in himâ]

â¢

[But Love's dispelled Emolument]

Has no retrieve in him

Affluence of time

(F 1660)

My reader can see for herself the difference that printing makes to the many possible lyrics that may be read out of the pages in

figures 7a

and

7b

; clearly it is Franklin who has made of Dickinson's scattered lines these pseudocouplets, thus making visible in print the genre Hegel would say that he had assumed. Although he did not decide to print the lines in

figure 5

as a poem, Franklin did decide to print some of the lines in

figures 7a

and

7b

as poetry, and further decided that the other lines are poetic variants or prose. We will return to the complex problem of reading Dickinson's proliferating variant lines, but Franklin's reading edition saves us from that problem altogether by printing only the one excised quatrain. In doing so, he follows established and not at all unusual editorial precedent in choosing between several manuscript possibilities.

23

He also follows the tradition of Dickinson's editors in assuming that what we want to discern among those possibilities is an individual poem. And, as Franklin wrote in reply to Susan Howe's now famous suggestion that Dickinson's manuscripts are themselves “artistic structures,” individual poems depend on discrete sets of lines. In response to Howe's opinion that Dickinson's manuscript line breaks were significant yet ignored in print, Franklin wrote that remarking “line breaks depended on an âassumption' that one reads in lines. He asked, âWhat happens if the form lurking in the mind is the

stanza

?'”

24

We will return to Howe's deeply lyrical interpretation of the difference between Dickinson-in-manuscript and Dickinson-in-print, but what the preceding pages have demonstrated is that a history of reading Dickinson lyrically has been made possible by a history of printing Dickinson lyrically. Since, as we saw in Hegel, all “texts are interdiscursive with respect to other text occasions, especially to relatively originary or precedential ones with respect to which a âreading,' for example, is achieved,” then we might say that the precedential text that has served as a point of reference for all readers and editors of the texts in

figures 7a

and

7b

, whether read in lines or stanzas, as visually significant or metrically conventional, as figurally or formally or historically lyrical, is the imaginary or originary lyric poem in print that Dickinson did not write.

25

The example of the

HOME INSURANCE CO. NEW YORK

sheets and their many editorial versions may seem to have taken us far afield from the interpretation of the lines on the right side of the envelope in

figure 5

(lines that are still hanging fire, I hope, over these pages, and to which we will return, returning as well to the lines that

have now intervened in

figures 7a

and

7b

), but they also return us to the hermeneutic problem of just how interdiscursive the “text occasion” of Dickinson's writing can be. While print versions of Dickinson's writing might lead us to believeâindeed, have led generations of readers to believeâthat the difficulty of reading Dickinson is that her brief lyrics hover one after the other on the white page out of context, the difficulty of reading Dickinson's manuscripts is that even in their fragmentary extant forms, they provide so much context that individual lyrics become practically illegible.

H

YBRID

P

OEMS

In his book

The Editing of Emily Dickinson

(his first on the subject, written prior to his becoming the editor of Emily Dickinson) in 1967, Franklin himself eloquently characterized the interpreter's dependence on acontextual “poems” that the critic must not admit are editorial fictions:

The contemporary critical climate rules that we consider the poems as poems, and here the difficult problem arises: just what

is

the relationship between the author and his work? Critically, we say that a work of art is not commensurate with its author's intentions, yet the basic text is recovered, edited, and printed on the basis of authorial intention (so that the critic can then go to work with the theory that it is not commensurate with those intentions). It is an anomaly within our discipline and one that is not always recognizedâ¦. A poem, one might argue, is a poem is a poem. Clearly, even an altered poem

is.

And within the context of poetry in general, criticism of such a poem is perfectly valid. The error, the deception, comes in passing off these poems as Emily Dickinson's. They are Dickinson-Todd-Higginson's. They are, quite simply, poetryâ¦. But we are not commonly organized in our pursuit of literature to talk about literature per se. Fortunately or unfortunately, authors are our categories, and there is little place for hybrid poemsâ¦. Academically raised in an era that believes in the sacredness of the author's text and that also believes in criticism divorced from authorial intention, we face a quandary with the Dickinson texts ⦠any approach that is exclusively author-oriented will fail editoriallyâ¦. If, then, we want the poems in a readers' edition, we are forced to make decisions. But this, too, can lead to the impossible. “Those fairâfictitious People” [now F 369] exists in a semi-final draft with twenty-six suggestions that fit eleven places in the poem. From this, 7680 poems are possibleânot versions but, according to our critical principles, poems.

26

As an aspiring critic, Franklin could see that a reading of Dickinson in manuscript is mathematically impossible; as an editor, he needed to take the poem out of its scriptive context in order to make a reading possible. In 1998, Franklin published only one of the 7,680 poems possible “according to our critical principles.” Franklin's editorial decision on a single Dickinson-Franklin lyric would have been impossible according to Franklin-the-critic, because by the middle of the twentieth century, the “critical climate rule[d] that we consider the poems as poems,” or “within the context of poetry in general.” What remains to be said is that the critical climate given such juridical (not to say institutional) power in 1967 ruled that we consider all poems as lyric poems, and all lyric poems as “verbal icons.” According to Wimsatt and Beardsley's influential description of the poem as verbal icon in 1954 (one year before the first scholarly edition of Dickinson's complete poems), to read a lyric is “to impute the thoughts and attitudes of the poem immediately to the dramatic

speaker,

and if to the author at all, only by way of an act of biographical inference.”

27

I will have much more to say in the next chapter about the New Critical lionizing of Dickinson as an ideally iconic (that is to say, acontextual) lyric poet, and much in the chapters that follow about the still dominant twentieth-century reading of Dickinson's poems (and of all poems) as a series of performances by fictional speakers or dramatic personae. For now we may simply note the distance between Higginson's and Aldrich's nineteenth-century figuration of Dickinson's writing as an author's attempt to represent birdsong and Franklin's view of the New Critical divorce from authorial intention. According to Franklin, “there is little space for hybrid poems” because after the nineteenth century lyrics are taken to be the utterance of a single subject, and after the middle of the twentieth century, that subject is not imagined as the author who, historically, inscribed the text. As Wimsatt and Beardsley wrote, “Judging a poem is like judging a pudding or a machine. One demands that it work. It is only because an artifact works that we infer the intent of the artificer” (71). Franklin's complaint against such New Critical principles of interpretation anticipates Foucault's famous description of the author as “the principle of thrift in the proliferation of meaning”âwith the important distinction that when twentieth-century critics such as Wimsatt and Beardsley read poetry, they want books to obey an economic law that they want the poems within those books to defy.

28

What critics want when they read lyric poetry, Franklin sensibly remarks, is not to have their author and have her, too. “According to our critical principles,” if an author wrote a line, the critic is bound to interpret it as part of a poem whether or not the author intended the line to be read as such. If the line “works,” that means that the author intended it to

work. Such principles, Franklin suggests, ignore “the principle of thrift” that what Foucault would call the “author function” imposes on “the proliferation of meaning.” The 7,680 poemsâImagine!âthat become possible, and printable, according to mid-twentieth-century lyric logic seem to Franklin a foolishly profligate proposition, as indeed they may be. The principle on which the poem is manufactured cannot be so liberally interpreted, or the poem (like a pudding or a machine) loses value in the literary economy. But while Franklin follows the logical contradiction inherent in his era's literary criticism to what he takes to be its absurd extreme, he is saved from what Hegel called “the awkwardness of the problem” because before he reached that extreme he had already decided that what Dickinson wrote was literatureânot “literature per se,” but lyric poems.