Dickinson's Misery (32 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Thus in the lecture entitled “On a Method of Searching for the Categories” (1866), the three aspects of the semioticâthe “ground,” the “correlate,”

and the “interpretant”âall exhibit, in Peirce's illustratively pragmatic examples, the phantasmatic “fact” of the incarnate letter. His remarkable instance of the primary “ground” of referential thought is the proposition, “Ink is black.” “Here,” Peirce writesâin one of many uses of the deictic to express the principle of deixisâ“the conception of

ink

is the more immediate; that of

black

the more mediate, which to be predicated of the former must be discriminated from it and considered

in itself

not as applied to an object but simply as embodying a quality,

blackness.

Now this

blackness

is a pure

species

or abstraction, and its application is entirely hypothetical.”

19

Although Peirce's term for “these conceptions between

being

and

substance

” is “

accidents,

” there is, I would argue, nothing accidental about his use of a thematics “embodying” writing to describe the process of cognition. In the proposition “Ink is black,”

ink

is the

substance

of the proposition. As such, according to Peirce, it has no

being,

for “to say that

substance

has being is absurd for it must cease to be substance before being or non-being are applicable to it.” The definition of a substance is, then, that it can only find “being”âwhich, for semiosis, must mean

meaning

âonly by embodying an apprehensible “quality”; it is this quality, and not the mute substance to which it attaches, that serves as the referential basis for the passage of perception into legibility. “We mean the same thing when we say âthe ink is black,'” Peirce writes, “as when we say âthere is blackness in the ink':

embodying blackness

defines

black.

” Because “

embodying blackness

defines

black,

” blackness becomes what Peirce calls a “pure abstraction,” an elementary conception that can “arise only upon the requirement of experience.” We experience blackness; ink embodies this experience; ergo, blackness gives meaning to what defines it

as

a referent. Blackness is what the ink-body means. And it may go without saying that in the United States in 1866, such a structure of meaning naturally (as it were) allows particular bodies to be signed into the cultural semantics of “blackness.”

20

This is to say that the theory of indexical meaning that Peirce developed turns personified abstractions into persons through the agency of the letter already embedded in the nineteenth-century American unconscious. The third, synthesizing stage of the semiotic, the stage of “Representation,” makes most explicitâand most problematicâthe logic that transforms ink into bodies and bodies into ink. Because Peirce sees clearly that referential meaning depends on the structure of a comparison (this he calls the “correlate”), it is his articulation of that structure that bears the weight of his theory. It is also, then, in his representative examples of representation, that we find the most complex and revealing description of the mutual implication of anatomized letters and literalized anatomies.

Because that mutual implication is best traced not only in the examples

themselves but in the way the logic moves

between

themâas Peirce would say, in the elementary conceptions entailed in their comparisonâI will cite the passage on representation at some length in order to ask my reader to attend to the analogies through which one substance becomes a quality and again a substance, one letter becomes a body and again a letter:

Reference to a correlate is clearly justified and made possible solely by comparison. Let us inquire, then, in what comparison consists. Suppose we wish to compare L and Î; we shall imagine one of these letters to be turned over upon the line on which it is written as an axis; we shall then imagine that it is laid upon the other letter and that it is transparent so that we can see that the two coincide. In this way, we shall form a new image which mediates between the two letters, in as much as it represents one when turned over to be an exact likeness of the other. Suppose, we think of a murderer as being in relation to a murdered person; in this case we conceive the act of the murder, and in this conception it is represented that corresponding to every murderer (as well as to every murder) there is a murdered person; and thus we resort again to a mediating representation which represents the relate as standing for a correlate with which the mediating representation is itself in relation. Suppose, we look out the word

homme

in a French dictionary; we shall find opposite to it the word

man,

which, so placed, represents

homme

as representing the same two-legged creature which

man

itself represents. In a similar way, it will be found that every comparison requires, besides the related thing, the ground and the correlate, also a

mediating representation which represents the relate to be a representation of the same correlate which this mediating representation itself represents.

Such a mediating representation, I call an

interpretant,

because it fulfills the office of an interpreter who says that a foreigner says the same thing which he himself says.

21

A transparent letter

L

; the act of murder; a two-legged creature; the translation of a foreign language: these are the instances Peirce offers to fulfill “the office” of representation. The story that this sequence itself tells about that office would fill volumesâbut let me just point to its cast of characters. First, enter the material letter

L

and its transposition: this character is “material” because it may be manipulated into a mark that can be

seen

but not read. According to Peirce, in order to turn seeing into “reference” (perception into cognition), we must literally translateâor carry overâone typeface to another: Î becomes “transparent” to

L

in this translation, “so that we can see that the two coincide.” What is canny about the instruction is that it mimes the interpretive practice that it also determines, thus making the unconditional agency of imagination (invoked by the passage's reiterated imperative, “

Suppose

⦔) seem “an exact likeness” of a literacy already

conditioning these terms. This example makes reading appear an empirical process by challenging the reader not to do it. We are not actually asked to recognize

L

as a letter of the roman alphabet or to interpret Î as, say, a Greek capital gamma; we are merely asked to superimpose these shapes by lifting them, in the mind, off of the page. The “new image” so lifted “mediates between the two letters” because it seems to simply reflect their anatomy rather than to construct their meaning.

Yet a murderer's relation to a murdered person could hardly be thought analogous to the “transparent” relation between a right-side-up and upside-down letter of the alphabetâor could it? In order to mediate between the terms of this second comparison, “we conceive the act of the murder,” an act that acts as the film through which we are to pictureâas if empiricallyâthe two as coincidental or the same. The potential violence of the as-if quality of the notion of an empirical identity begins to emerge here as a property not only of the image of murder but of the image of the letter (and even of the -

er

suffix that transliterates one into the other). That potential then underwrites, as it were, Peirce's third example, in which he anthropomorphizes the relation between the imaginary play of the letter and the corpse it may leave in its wake. What unites the French

homme

and the English

man

is not the French dictionary, which merely places one word “opposite” to another, but the idea of a “two-legged creature.” The representation produced by the facing-off of the two words in the lexicon (which acts, by the way, like the “new image” in the passage's first example and like the ink in Peirce's earlier proposition, as the mute reflective substance of this apposition, its mirror) has a long history in letters. From Oedipus's riddle to Shakespeare's “bare forked animal,” the two-leggedness of the “creature which

man

itself represents” has stood as the problematic figure of the human sacrifice entailed in the semiosis of the human. The potentially tragic consequences of anatomizing

h

-

o

-

m

-

m

-

e

or

m

-

a

-

n as if

the word were not itself the creature of Western strategies of representationâthat is, as if an alphabet could be translated into perception as a transparently self-identified bodyâmay cause Peirce to “say the same thing which he himself says,” and yet to end up writing something different.

The difference inherent in each of Peirce's suppositions is the subjective agency invoked in and as the very “mediating representation” that is directed to translate them as instances of the same. His description ends up performing exactly the opposite “office” than the one it states as its purpose because he grounds it in the anatomical imaginary his thought implicitly associates with the materiality of writing. Walter Benn Michaels and Michael Fried have argued that such an association characterizes various American texts of the second half of the nineteenth century in which

“writing as such becomes an epitome of a notion of identity as difference from itself (in that writing

to be

writing must in some sense be different from the mark that simply materially it is); and that this is important above all because, in those texts and others, the possibility of difference from itself emerges as crucial to a concept of personhood that would distinguish persons from both pure spirit ⦠and from pure matter.”

22

If indeed Michaels and Fried are right to point to writing as “an epitome” of mid-to-late nineteenth-century versions of subjectivity, even my brief examples from Higginson and Peirce suggest that they may be cutting off (that is, themselves

epitomizing

) half of the analogy's point.

What mediates between spirit and matter, what a letter means and what a letter is? For both Higginson and Peirce, and, I would argue, for Fried and Michaels, the function that Peirce would call the “interpretant” is performed by literature. Literary figures explain the relation between anatomy and letters. In the second half of this chapter, I will turn to some of the ways in which Dickinson associated her culture's rhetorical inscription of personhood with various forms of literary mediation. Because the relation between the ideality and materiality of personhood and the ideality and materiality of writing is, as we have seen, already embedded in the discourse of the genre that has come to define Dickinson's writing, her associations often turn a precise and excruciating focus on the role of the lyric reader who, like Higginson and Peirce and their twentieth-century successors, would suppose that letters could referâeven in their differencesâto bodies.

O

B

IRDâYET RODE IN

E

THER

â”

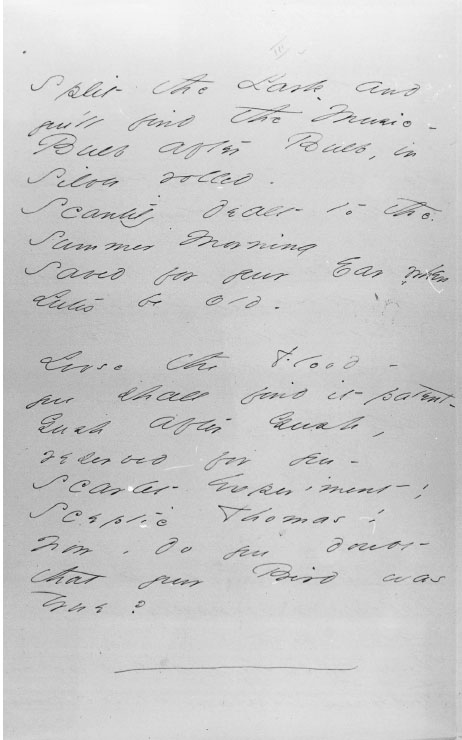

Consider what the following short text from one of the unbound sets (

fig. 28

; set 5), written toward the end of the war in early 1865, does to the notion of subjectiveâand anatomically inscribedâlyric reference:

Split the Larkâand

you'll find the Musicâ

Bulb after Bulb, in

Silver rolledâ

Scantily dealt to the

Summer Morning

Saved for your Ear, when

Lutes be old

Loose the Floodâ

you shall find it patentâ

Figure 28. Emily Dickinson, 1865. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED ms. No. 87-3, verso).

Gush after Gush,

reserved for youâ

Scarlet Experiment!

Sceptic Thomas!

Nowâdo you doubt

that your Bird was

true? (F 905)

This text stages the act of its own reading in sadomasochistic terms. What is perhaps less obvious about this rather offensive staging is that its terms are drawn from a nineteenth-century discourse already troubled by the approach to writtenâand particularly literaryârepresentation that Dickinson here parodies. By “perhaps less obvious,” I mean that literary critics since 1896, when these lines were first printed as a lyric, have consistently interpreted it as the poet's lyrical send-up of scientific empiricism. An anonymous reviewer for the 1896

Boston Beacon

went so far as to suggest that it be read as the bird's dramatic monologue: “Miss Dickinson rarely falls into another's manner,” the reviewer remarks, “but could Browning himself have bettered this?” Such an odd aesthetic apprehension of Dickinson's text may be due in part to the rather odd title given the poem by Todd: “Loyalty.” The literary framingâgenre identification, bound publication, title, critical reviewâseems to have invited a legacy of the sort of educated response that Higginson (that other reader of Browning) would have counted on. Thus a more recent critic explains that “the poem's real meaning is inverted” so that rather than cooperating with the demand for proof, “this poetic experiment effectively disposes of the empirical approach.”

23

One sees the point: poetic trope reverses apparent meaning, whether in the Victorian personage of a dramatic speaker, or in the New Critical understanding of the artistic function of irony. Either way, the image that mediates between the letters on the page and their “real” meaningful inversion is Literature (and especially lyric) with a capital

L

. Yet lyricâor, specifically, the reading of it as indexical cultural identityâmay itself be the object of Dickinson's perverse anatomy lesson.