Which Way to the Wild West? (8 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

T

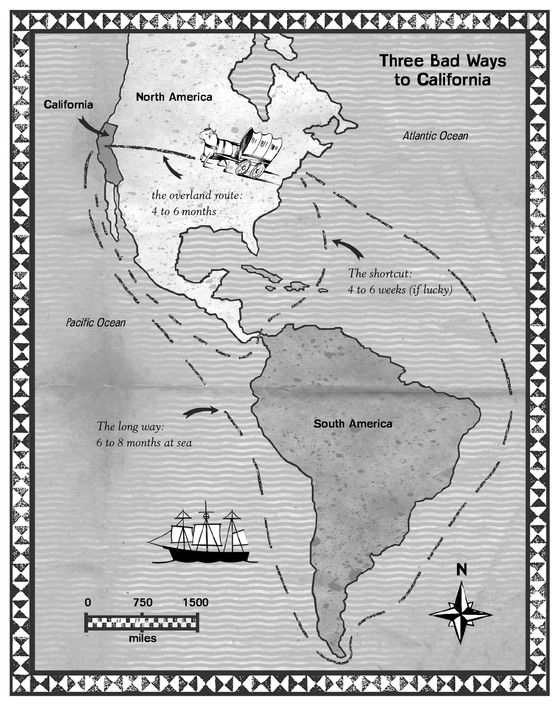

here was no good way to get to California. There were three bad ways.

here was no good way to get to California. There were three bad ways.

First, you could cross the country by land, using oxen to drag your wagons along the trails to the western coast. This was bonebruising, slow, and dangerousâand getting more dangerous all the time. As the trails got busier, streams and wells along the way got more and more polluted with human waste. This led to the spread of cholera, an infection of the intestines that causes severe diarrhea and vomiting. Death was often miserable and quick, as a traveler named William Swain noted in his diary:

May 18:

One of our company, Mr. Ives, is sick with cholera.

One of our company, Mr. Ives, is sick with cholera.

May 19:

Mr. Ives is dead.

Mr. Ives is dead.

If you had about six hundred dollars to spare (which most people didn't) you could travel by sea all the way around the southern tip South America and then north to California. This was safer than the overland trails, though you had to deal with storms, seasickness, rotting food, and barrels of drinking water that got so smelly, passengers had to add molasses and vinegar before they could bear to swallow it. For many, though, the real problem with this route was that it was 15,000 miles and took six months or moreâtoo long to wait when you've got gold fever.

The quickest route (if everything went well) was to sail to Panama, cross the seventy-five-mile-wide strip of land by canoe and on foot, and then get in another ship bound for California. Shipping company advertisements made this sound like a pleasant little shortcut. The ads failed to mention that travelers would be tripping through tropical forests and dodging disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Nor did the ads mention that when you finally stumbled into Panama City, there would probably be no ship there to pick you up. Jenny Megquier and her husband were among thousands of travelers who got stuck on Panama's Pacific coast. Every time a boat sailed

up, desperate crowds raced forward to try to get on. Megquier kept a positive attitude while waiting, though she did find some of the local bugs mildly annoying. “Another insect which is rather troublesome, gets into your feet and lays its eggs,” she wrote. The doctor and I have them in our toesâdid not find it out until they had deposited their eggs in large quantities; the natives dug them out and put on the ashes of tobacco.”

up, desperate crowds raced forward to try to get on. Megquier kept a positive attitude while waiting, though she did find some of the local bugs mildly annoying. “Another insect which is rather troublesome, gets into your feet and lays its eggs,” she wrote. The doctor and I have them in our toesâdid not find it out until they had deposited their eggs in large quantities; the natives dug them out and put on the ashes of tobacco.”

Jenny Megquier eventually made it to California alive. So did William Swain and about 10,000 other hopeful people in 1848.

G

etting there was just the start of the adventure. A young traveler named Leonard Kip realized this when his ship sailed into San Francisco's harbor. Kip woke to the sounds of the ship's captain barking curses. He found an officer and asked what was going on.

etting there was just the start of the adventure. A young traveler named Leonard Kip realized this when his ship sailed into San Francisco's harbor. Kip woke to the sounds of the ship's captain barking curses. He found an officer and asked what was going on.

Kip:

What's the matter?

What's the matter?

Officer:

You will have to row yourselves ashore, as all the men have left.

You will have to row yourselves ashore, as all the men have left.

Kip:

Indeed!

Indeed!

Officer:

Went off last night, on the sly, laughing at us on shore nowânext week, in the mines.

Went off last night, on the sly, laughing at us on shore nowânext week, in the mines.

This was happening a lot. As soon as ships arrived in San Francisco, entire crews raced to shore and headed inland to join the gold rush. Kip looked around and saw the result: hundreds of ships gently rocking in the harbor. They were flying flags from all over the world. They were all empty.

Kip got the feeling he was entering a very strange new world.

One day in September 1848 an African American miner was walking along the San Francisco waterfront. He heard someone calling to himâit was a wealthy white traveler who wanted someone to carry his bags. This guy may have been used to bossing around slaves back east. But things were different out west. The black man pulled a bag from his pocket, showed off more than one hundred dollars in gold, and said: “Do you think I'll lug trunks when I can get that much in one day?”

“T

his is the best place for black folks on the globe,” one black miner wrote to his wife in Missouri. “All a man has to do is to work, and he will make money.” This was enough to draw African Americans to California from all over the United States. Some were escaping from slavery; some were free men hoping to find enough gold to buy the freedom of family members still enslaved in the South.

his is the best place for black folks on the globe,” one black miner wrote to his wife in Missouri. “All a man has to do is to work, and he will make money.” This was enough to draw African Americans to California from all over the United States. Some were escaping from slavery; some were free men hoping to find enough gold to buy the freedom of family members still enslaved in the South.

“What a puzzling place it was!” Leonard Kip said soon after stepping ashore. “A continual stream of active population was winding among the casks and barrels, which blocked up the place where the sidewalks ought to have been.”

Kip was amazed by the diversity of the crowds: white and black Americans, Chinese, Mexicans, Germans, Chileans, Irish, Native Americans, Hawaiiansâall with different styles of hair and dress, speaking different languages, racing between stores, bars, music halls, and gambling houses. “The town seems running wild after amusement,” he said.

And wild after money too. By the time travelers got to San Francisco they were so feverish to find gold that some started digging for it right in the streets of town. And they often found it! What they didn't know was that the streets had been “salted,” or secretly sprinkled with gold dust. This was done by creative store owners who wanted to get people excited, then sell them mining gear at shockingly high prices.

Another clever merchant heard complaints about the enormous rats that were eating (and pooping on) all the food in the city. He imported a ship full of cats from Mexico. They sold out quickly (at eight to twelve dollars each).

Then there was the guy who declared he was a doctor and started seeing patients. No one in town was aware that he had no medical training at allâuntil someone he knew from back east showed up and demanded: “What do you know about being a doctor?”

“Well, not much,” the man admitted. In his own defense he added: “I kill just as few as any of them.”

Luckily for this guy, people were too busy making money to worry about small details. One such detail: the city's dirt streets got so muddy that crates, dogs, horses, and sometimes people, actually sank under the surface and rotted beneath the stinky brown ooze. (A sign on one street warned travelers that the way was not safe for man or beast: “This street is impassable, not even jackassable.”)

People were too busy to worry that no one nearby was growing food, and that everything had to be shipped in from thousands of miles away. The result was incredibly high prices. “Money here goes like dirt; everything costs a dollar or dollars,” said an astonished twenty-one-year-old named Enos Christman. Back home he could have bought a big bag of potatoes for a few pennies. “Today I purchased a single potato for forty-five cents.”

But what did any of this matter when there was gold to be found? Most people stayed in town only long enough to buy supplies. Then they headed east for what they called “the diggings”âthe gold-rich streams flowing down from the Sierra Nevada.

A

s soon as he arrived at the diggings, a hopeful miner from Britain named William Ryan ran into an old friend.

s soon as he arrived at the diggings, a hopeful miner from Britain named William Ryan ran into an old friend.

“Good morning, Firmore,” Ryan said to his friend.

“What, you!” Firmore shouted, shaking Ryan's hand. “How did you come, and where did you start from? You are looking all the worse for wear.”

Ryan looked over his friendâat his shredded clothes, his filthy whiskers, his face caked with dirt. “I can't say you look quite as dapper, Firmore, as you did the day we went ashore.”

Firmore confessed that he had been having tough times. “For several days after I got here, I did not make anything,” he explained. “But since then I have, by the hardest work, averaged about seven dollars a day.”

William Ryan

This surprised Ryan. Like most new miners, he knew nothing about gold mining. But he imagined it was pretty easy. You just bend down and collect the shiny nuggets, right?

“Ah! It's more luck than anything,” Firmore said. “But, luck or no luck, no man can pick up gold, even here, without the very hardest labor, and that's a fact. Some think that it is only to come here, squat down anywhere, and pick away. But they soon find out their mistake. I never knew what hard work was until I came here.”

When you read letters and journals of miners in California, you see lots of stories like Firmore's. People came with dreams of scooping up glittering lumps of gold. And this did happen once in a while (one miner found a hunk of solid gold weighing 195 pounds). But most miners spent long days squatting in chilly streams, scooping up pans full of dirt. After filling the pan with water, the miner gently rocked the pan back and forth, allowing the water to carry off the dirt little by little. Flakes and dust-size bits of gold (if there were any) collected at the bottom of the pan, because gold is about eight times heavier than dirt.

“There is gold here in abundance,” one miner said of the California diggings. “But it requires patience and hard labor, with some skill and experience to obtain it.”

Or, as another disappointed miner put it: “The chances of making a fortune in the gold mines are about the same as those in favor of drawing a prize in a lottery.”

There was still good money to be made, though. Miners who were lucky enough to find a good spot, and who worked from sunup to sundown, were often able to collect one to two ounces of gold a day. An ounce of gold was worth sixteen dollars. Back east, in comparison, skilled workers earned about $1.50 for a twelve-hour day.

So you can see why people kept coming to California. As one miner explained to his wife: “I am willing to stand it all to make enough to

get us a home, and so I can be independent of some of the darned [censored] that felt themselves above me because I was poor.”

get us a home, and so I can be independent of some of the darned [censored] that felt themselves above me because I was poor.”

N

early 100,000 people raced to California in 1849. They even earned their own nickname: “forty-niners.” Thousands more were on the way. In fact, this was the largest movement of people the world had ever seen. Gold can do that.

early 100,000 people raced to California in 1849. They even earned their own nickname: “forty-niners.” Thousands more were on the way. In fact, this was the largest movement of people the world had ever seen. Gold can do that.

One result: the most promising gold mining spots were getting crowded with tents, shacks, and miners. And garbage. One miner described walking along a stream “strewn with old boots, hats, shirts, old sardine boxes, empty tins of preserved oysters, empty bottles, worn-out pots and kettles.”

Desperate miners were digging in the streams, along the banks, even in the streets of the mining camp. One woman found gold flakes while sweeping the dirt floor of her shack. She shoved aside the table, started digging, and found hundreds of dollars' worth of gold.

Most miners' experience was more like that of William Swain, who had come west from his farm in New York. “My first day's work in the business was an ounce,” he wrote to his wife. “The second was $35, and third was $92.” That was followed by day after day when he found nothing. Meanwhile, the high price of food and supplies was eating away at his little pile of gold. Swain had boldly promised to bring home $10,000. “As soon as I can get the rocks in my pocket I shall hasten home as fast as steam can carry me,” he told his family.

“O! William, I cannot wait much longer,” his wife, Sabrina, wrote to him. “I want to see you so bad.”

“I must have the $10,000,” Swain insisted.

But in a letter to his brother, Swain admitted that things were going badly. “George, I tell you, mining among the mountains is a dog's life,” he said. He even warned George to give up any dreams of gold mining. “There was some talk between us of your coming to this country,” Swain wrote. “For God's sake think not of it. Stay at home.”

Still, Swain was committed to staying long enough to make his fortune. So were thousands of others. Just how eager were these miners to find some gold? One day at a mining camp, a miner died and his friends gathered for the funeral. They knelt around an open grave as a fellow miner (and former minister) started reading some prayers.

After a few minutes, the minds of the grieving miners started drifting toward dreams of gold. Their hands started sifting through the dirt that had been dug up from the grave.

The minister saw that the men weren't paying attention to the service. He opened his mouth to complain, but then he noticed what they had noticedâyellow flecks in the dirt.

“Boys, what's that?” he asked. He took a closer look, then answered his own question:

“Gold! And the richest kind o' diggings!

The congregation are dismissed!”

The dead man was dragged away to be buried somewhere else, while the minister ran off for his mining shovel and pan.

Other books

What Never Happens by Anne Holt

Z-Burbia 3: Estate Of The Dead by Bible, Jake

Wolf's Lady (After the Crash Book 6.5) by Maddy Barone

Without You by Kelly Elliott

In Plain View (Amish Safe House, Book 2) by Ruth Hartzler

A Life Worth Living by Irene Brand

Enslaved in Shadows by Tigris Eden

Crash Into You by Roni Loren

The Sapphire Brooch (The Celtic Brooch Trilogy Book 2) by Logan, Katherine Lowry

Lady In Distress (The Langley Sisters Book 3) by Vella, Wendy