Which Way to the Wild West? (11 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

“I was just eighteen, and boy-like, craved such excitement,” remembered a Pony Express rider named William Campbell. But as Campbell quickly realized, galloping across the West was, as he put it, “more hard work than fun.” During one run Campbell nearly crashed into a pack of bloody-faced wolves that were ripping flesh from some big dead thing. “They refused to move when I rode at them,” he said, “and my horse shied at the smell of blood and animals.” Campbell swerved around the wolves and raced on.

T

he Pony Express started doing business in April 1860. For five dollars a letter, you could have Express riders carry your mail from Missouri (where the eastern railroads ended) 1,950 miles to California in just ten daysâby far the fastest mail service available at the time.

he Pony Express started doing business in April 1860. For five dollars a letter, you could have Express riders carry your mail from Missouri (where the eastern railroads ended) 1,950 miles to California in just ten daysâby far the fastest mail service available at the time.

The whole thing worked like a giant relay race. Each rider was assigned a section of the route, usually about eighty miles. The rider's job was to speed across his section, stopping at stations every ten or fifteen miles to change horses. At the end of his route, the rider handed the mailbags to the next guy. Then he could collapse onto a cot for a few hours before jumping up, grabbing new mail sacks, and racing back the other way.

The company liked to hire young men, tough teenagers who had grown up riding horses. When Elijah Wilson took the job, he was told the most important rule: “When we started out we were not to turn back, no matter what happened.” This made life dangerous for riders, especially as they crossed Native American territory. Indians didn't welcome riders cutting through their hunting grounds, using their scarce water resources.

One day Wilson was stopped by an Indian warrior and given a warning. “He said I had no right to cross their country,” Wilson remembered. “The land belonged to the Indians, and they were going to drive the white men out of it.” But turning around was not an option.

While resting at a station in Nevada a while later, Wilson and a few other riders were attacked. “One of the Indians shot me in the head with a flint-tipped arrow,” he said. His friends tried to pull out the arrow, but the pointed stone stuck fast in his skull. “Thinking that

I would surely die, they rolled me under a tree and started for the next station as fast as they could go. “They got a few men and came back the next morning to bury me; but when they got to me and found that I was still alive, they thought they would not bury me just then.”

I would surely die, they rolled me under a tree and started for the next station as fast as they could go. “They got a few men and came back the next morning to bury me; but when they got to me and found that I was still alive, they thought they would not bury me just then.”

Wilson lay unconscious for the next eighteen days. “Then I began to get better fast,” he remembered. “It was not long before I was riding again.”

The Pony Express failedâbut obviously not because the riders weren't tough enough. The real problem was, it was just too expensive to maintain all those stations, horses, and riders. The company lost money steadily. Then, in October 1861, American engineers finished building the first transcontinental telegraphâa telegraph line all the way across the country. Suddenly short messages could

be sent over wires from east to west. That put the Pony Express out of business once and for all.

be sent over wires from east to west. That put the Pony Express out of business once and for all.

The telegraph was the perfect technology for quick communication. But was there any way to move people and goods across the country more quickly? Yes: build a transcontinental railroad.

The only problem? No one had ever built a railroad that long. Most Americans were pretty sure it was impossible.

T

heodore Judah disagreed. Growing up in New York, Judah had enrolled in college engineering classes when he was eleven. He began designing railroads when he was still a teenager. By 1861 Judah was in California, thinking about building a transcontinental railroad. “It will be built,” he said over and over, “and I am going to have something to do with it.”

heodore Judah disagreed. Growing up in New York, Judah had enrolled in college engineering classes when he was eleven. He began designing railroads when he was still a teenager. By 1861 Judah was in California, thinking about building a transcontinental railroad. “It will be built,” he said over and over, “and I am going to have something to do with it.”

Judah's wife, Anna, said that her husband talked so much about the railroad, he was beginning to annoy the entire city of Sacramento. He would corner people on the street and start describing his plans.

Anna would nudge him and whisper, “Theodore, those people don't care.”

“But we must keep the ball rolling,” he would insist.

And Californians really did want a railroad to connect them to the rest of the country. They just didn't think it could be done. For starters, how could anyone build tracks up and over the sharp slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain range? Judah kept insisting he could do it. That's when people started calling him “Crazy Judah.”

Never one to be easily discouraged, Judah made more than twenty trips into the Sierra Nevada, carefully mapping out the route

a railroad could take. Anna often came along to make drawings and paintings of the route. All this work finally began to pay off when a group of local business owners agreed to invest some money to start building the railroad east out of Sacramento.

a railroad could take. Anna often came along to make drawings and paintings of the route. All this work finally began to pay off when a group of local business owners agreed to invest some money to start building the railroad east out of Sacramento.

Theodore rushed to his wife with the news:

“Anna, if you want to see the first work done on the Pacific railroad, look out your bedroom window. I am going to work there this morning and I am going to have these men pay for it!”

“It's about time that someone else helped!” Anna said.

It was a good start, but Judah knew that a project this massive would require thousands of workers and millions of dollars. So he packed up his maps and Anna's paintings and sailed to Washington to persuade government leaders to support the transcontinental railroad. Judah showed up in the capital in October 1861âjust as the Civil War was ripping the United States in two. In a weird way, his timing was pretty good.

T

he new president of the United States was Abraham Lincoln (turns out his opposition to the U.S.-Mexican War didn't end his career in politics after all). Lincoln was all for the transcontinental railroad, saying it was “demanded in the interests of the whole country.” Or, what was left of the whole country. Eleven states had just dropped out of the Union. Lincoln was desperate not to lose any moreâespecially not California (and its gold). His hope was that a rail line from the East to the West would help bind California to the rest of the United States.

he new president of the United States was Abraham Lincoln (turns out his opposition to the U.S.-Mexican War didn't end his career in politics after all). Lincoln was all for the transcontinental railroad, saying it was “demanded in the interests of the whole country.” Or, what was left of the whole country. Eleven states had just dropped out of the Union. Lincoln was desperate not to lose any moreâespecially not California (and its gold). His hope was that a rail line from the East to the West would help bind California to the rest of the United States.

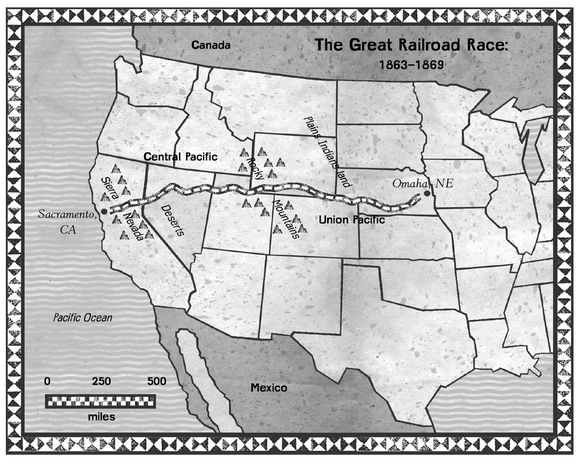

In the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, Congress declared that two companies would basically race to build the transcontinental railroad. Theodore Judah and his Central Pacific Railroad would start in Sacramento and build east. At the same time, the Union Pacific Railroad would build west from Nebraska, where the current westbound rail lines ended. The government would pay each company for every mile of track completed. Both companies could continue building, and collecting money, until they ran into each otherâwherever that happened to be.

The race was on.

“T

his is the grandest enterprise under God!” declared one Union Pacific investor when the work began in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1863. Turns out it was also a grand opportunity to rip off the American taxpayer. The Union Pacific vice president Thomas Durant was honest about this (in private, that is). He outlined his plan:

his is the grandest enterprise under God!” declared one Union Pacific investor when the work began in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1863. Turns out it was also a grand opportunity to rip off the American taxpayer. The Union Pacific vice president Thomas Durant was honest about this (in private, that is). He outlined his plan:

“Grab a wad of money from the construction feesâand get out.”

Durant's scheme was pretty confusing, but here's the basic idea. He set up a construction company, keeping it secret that he actually controlled it. Then he had the Union Pacific hire his construction company to build the railroad. His company starting building on the flat land along the Platte River. Construction cost about $30,000 a mile. But he had his company claim that the work was costing $50,000 a mile. The Union Pacific collected money from investors and the government, then used that money to pay Durant's construction company $50,000 per mile. Durant's company pocketed the extra $20,000. (Members of Congress didn't complain, possibly because Durant had quietly handed many of them stock in his company.)

Thomas Durant

The UP's chief engineer, Peter Dey, sensed that something suspicious was happening. “No man can call $50,000 per mile for a road up the Platte Valley anything else but a big swindle,” he said.

D

ey was even more upset when Durant starting messing with the route of the railroad. Dey designed a road that went out of Omaha and headed straight west for fourteen miles. To Durant, this was a wasted opportunity. The government was paying for every mile of track, right? So Durant brought in a different engineer to design a new routeâone with a big, totally unnecessary curve that added nine miles to the route.

ey was even more upset when Durant starting messing with the route of the railroad. Dey designed a road that went out of Omaha and headed straight west for fourteen miles. To Durant, this was a wasted opportunity. The government was paying for every mile of track, right? So Durant brought in a different engineer to design a new routeâone with a big, totally unnecessary curve that added nine miles to the route.

“This part of the road was located with great care by me,” Dey objected.

Durant ignored the objection. Dey quit in protest. The work went on without him.

I

n California the four directors of the Central Pacific, known as the “Big Four,” were working some schemes of their own. The Pacific Railroad Act declared that the government would pay the railroad companies extra for each mile of track built through mountains. This was fair, since it was more difficult and expensive to construct railroads through mountains. It gave the Big Four an idea.

n California the four directors of the Central Pacific, known as the “Big Four,” were working some schemes of their own. The Pacific Railroad Act declared that the government would pay the railroad companies extra for each mile of track built through mountains. This was fair, since it was more difficult and expensive to construct railroads through mountains. It gave the Big Four an idea.

The Sierra Nevada slopes began rising about twenty miles east of Sacramento. But the Big Four hired an expert geologist to declare that the mountains actually started just seven miles east of town. To nonexperts the land looked flat. But the expert insisted it was really a mountain. The Big Four sent the geologist's report to Washington, charging the government the higher rate to build tracks over

this “mountainous” land. And the Central Pacific collected an extra $500,000 in government payments.

this “mountainous” land. And the Central Pacific collected an extra $500,000 in government payments.

“There is cheating on the grandest scale in all these railroads,” declared the

New York Herald.

Theodore Judah agreed. And as the railroad's chief engineer, he refused to accept such bogus profits. He charged into the offices of the Big Four, and some serious shouting matches followed. Angry and frustrated, Judah sailed from California to New York in October 1863. His hope: to find new investors to buy the Central Pacific. He started feeling feverish while crossing Panama, and by the time he reached New York City he was flat on his back and barely conscious. His wife, Anna, had him carried ashore and put in a carriage. “I kept him up by dipping my finger in the brandy bottle and having him take it that way,” she said.

New York Herald.

Theodore Judah agreed. And as the railroad's chief engineer, he refused to accept such bogus profits. He charged into the offices of the Big Four, and some serious shouting matches followed. Angry and frustrated, Judah sailed from California to New York in October 1863. His hope: to find new investors to buy the Central Pacific. He started feeling feverish while crossing Panama, and by the time he reached New York City he was flat on his back and barely conscious. His wife, Anna, had him carried ashore and put in a carriage. “I kept him up by dipping my finger in the brandy bottle and having him take it that way,” she said.

That was about all Anna could do for her husband. He died of yellow fever a week later, at age thirty-seven, and was buried beneath a tombstone that read, “He rests from his labors.”

Other books

Book of the Guardian 3: The Last Mission by Ben Winston

Every Move You Make by M. William Phelps

Animal Appetite by Susan Conant

The Smoke is Rising by Mahesh Rao

This One and Magic Life by Anne C. George

Lipstick & Stilettos by Young, Tarra

The Queen of All that Dies (The Fallen World Book 1) by Thalassa, Laura

1 Shore Excursion by Marie Moore

The Immortal Circus: Final Act (Cirque des Immortels) by Kahler, A. R.

Death Be Not Proud by John J. Gunther