Which Way to the Wild West? (14 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

T

he Union Pacific was having a better time.

Possibly too good,

thought Frances Casement. Like Americans everywhere, she was following the railroad race in her daily newspaper. The more she read, the more she worried. She wrote to her husband, Jack, who was in charge of construction crews for the Union Pacific, saying: “Dear Jack, Do get home as soon as possibleâand darling, be careful of your healthâand for the sake of our little boy more than for your own sake, beware of the tempter in the form of strong drink.”

he Union Pacific was having a better time.

Possibly too good,

thought Frances Casement. Like Americans everywhere, she was following the railroad race in her daily newspaper. The more she read, the more she worried. She wrote to her husband, Jack, who was in charge of construction crews for the Union Pacific, saying: “Dear Jack, Do get home as soon as possibleâand darling, be careful of your healthâand for the sake of our little boy more than for your own sake, beware of the tempter in the form of strong drink.”

Frances had been reading stories about the wild towns springing up along the railroad tracks. As soon as railroad workers arrived in a new spot, other folks rushed in to set up bars and gambling houses. Some came simply to steal. “There are men here who would murder a fellow creature for five dollars,” reported one journalist in a Nebraska town. “Nay,” he added, “there are men who have already done it.” A newspaper in another town along the tracks actually ran a daily column called “Last Night's Shootings.” (They weren't all shootings: in

Paint Rock, Nebraska, two girls killed their sleeping stepmother by pouring melted lead into her ear.)

Paint Rock, Nebraska, two girls killed their sleeping stepmother by pouring melted lead into her ear.)

All of this helped sell newspapers, but none of it slowed down the speeding Union Pacific. Jack Casement worked his men hard all day, then lit bonfires along the tracks and had other crews work all night. “We are now sailing,” he reported, “and mean to lay over three miles every day.”

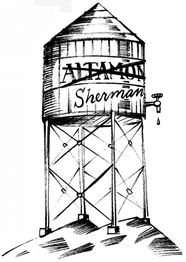

General Sherman was working hard to protect workers from Indian attacksâand the Union Pacific was working hard to keep Sherman happy. A UP official named Herbert Hoxie told Sherman that the railroad had decided to name a water station in his honor. (Trains stopped at these stations to fill up on water, which was needed to run the steam engines.) This conversation followed:

Sherman:

Where is it?

Where is it?

Hoxie:

[pointing to a map] Down here in Nebraska.

[pointing to a map] Down here in Nebraska.

Sherman:

Oh, I don't want a water station named after me. Why, nobody will live there. Where is the highest point on the road?

Oh, I don't want a water station named after me. Why, nobody will live there. Where is the highest point on the road?

Hoxie:

Altamont.

Altamont.

Sherman:

Just scratch out that name, and put down mine.

Just scratch out that name, and put down mine.

And that's how Sherman, Wyomingâthe station at the highest elevation along the Union Pacificâgot its name. (Sherman might be sad to know it's a ghost town today.)

I

n 1868 the Central Pacific workers finally finished what many had said was impossibleâthey busted through the mountains of California. Suddenly the CP started to pick up speed as it built tracks across the flat Nevada desert.

n 1868 the Central Pacific workers finally finished what many had said was impossibleâthey busted through the mountains of California. Suddenly the CP started to pick up speed as it built tracks across the flat Nevada desert.

In need of extra hands to keep the work cruising along, the railroad hired Paiute and Shoshone workers. This actually caused a brief delay when some of the Indians told Chinese workers that out in the desert ahead slithered enormous snakes that swallowed men whole. It was meant as a joke, of course. But these Chinese crews had seen enough danger for ten lifetimes, and a few hundred of the men decided it was time to head back to San Francisco. Other Central Pacific workers had to ride after them and plead with them to come back to work.

To the Central Pacific's Big Four, speed was everything now. They were determined to build as quickly as possible and collect as much money as possibleâeven if it meant building tracks that would soon fall apart. “The line we construct now is the one we can build the soonest, even if we rebuild immediately,” said one CP engineer.

Didn't this present a problem when government inspectors came to look at the quality of the track? Not really, said a

San Francisco Chronicle

reporter named W. H. Rhodes, who watched one of these government inspections in Nevada. Rhodes noticed that whenever the train stopped for water, the CP's Charles Crocker handed out another round of whiskey to the government inspectors. “In truth

we became hilarious,” reported Rhodes (

hilarious

was nineteenthcentury slang for “really drunk”).

San Francisco Chronicle

reporter named W. H. Rhodes, who watched one of these government inspections in Nevada. Rhodes noticed that whenever the train stopped for water, the CP's Charles Crocker handed out another round of whiskey to the government inspectors. “In truth

we became hilarious,” reported Rhodes (

hilarious

was nineteenthcentury slang for “really drunk”).

One of the inspectors soon fell asleep face-down on the floor of the train. Crocker insisted that the man could continue his inspection that way: “If the passengers could sleep, the track must be level, easy, and all right; whereas, if too rough to sleep, something must be wrong with the work.” The inspector was able to stay asleep. When he woke up, he gave his official approval to the tracks, and the government money continued rolling in.

T

he Union Pacific was doing the same thingâbuilding crummy track as quickly as possible. To keep the tracks moving during winter, UP workers even built tracks on top of ice!

he Union Pacific was doing the same thingâbuilding crummy track as quickly as possible. To keep the tracks moving during winter, UP workers even built tracks on top of ice!

Work crews for both companies started speeding through Utah in 1869. In fact, they sped right past each other. Eager to build as many miles of track as possible, the two companies went right past the meeting point and starting building railroads right next to each other in opposite directions.

Realizing that the race was getting ridiculous (and expensive), Congress forced the heads of the two companies to pick a spot for the rails to meet. They agreed to join their tracks at Promontory Summit, Utah. This made the final track-building score:

Union Pacific:

1,086 miles of track from Omaha to Promontory Summit

1,086 miles of track from Omaha to Promontory Summit

Central Pacific:

690 miles of track from Sacramento to Promontory Summit

690 miles of track from Sacramento to Promontory Summit

The Union Pacific may have built more track, but the Central Pacific's Charles Crocker had his eye on some history of his own. Union Pacific workers held the record for the most miles of track laid in a day, with eight. Charles Crocker announced that his men would beat the record. But he wanted to make sure that once he set the record it would stay set. “We must not beat them until we get so close together that there is not enough room for them to turn around and outdo me,” Crocker told his construction boss, James Strobridge.

“How are you going to do it?” Strobridge asked.

“I have been thinking over this for two weeks and I have it all planned,” Crocker said.

Crocker waited until his men reached the flat stretch of land close to Promontory Summit. He promised his Chinese and Irish work crews four days' wages if they could build ten miles of track in a day.

No problem,

they told him

No problem,

they told him

Beginning before sunrise on April 28, the well-organized teams finished six miles by lunchtime. They took an hour lunch break, then built another four miles and fifty-six feet of good-quality track by sundown. (The most amazing thing about the ten-mile day: just one eight-man team lifted every single seven-hundred-pound iron rail used that dayâmeaning each man carried 2.1 million pounds of iron.)

O

n the sunny spring morning of May 10, 1869, people gathered at Promontory Point, Utah, to witness the meeting of the two railroads. Newspaper reporters got out their notebooks, bands started warming up, and liquor sellers set up tents by the tracks. “Everyone had all they wanted to drink all the time,” said Alexander Toponce, who was there on the historic day. “I do not remember what any of the speakers said, but I do remember that there was a great abundance of champagne.”

n the sunny spring morning of May 10, 1869, people gathered at Promontory Point, Utah, to witness the meeting of the two railroads. Newspaper reporters got out their notebooks, bands started warming up, and liquor sellers set up tents by the tracks. “Everyone had all they wanted to drink all the time,” said Alexander Toponce, who was there on the historic day. “I do not remember what any of the speakers said, but I do remember that there was a great abundance of champagne.”

Union Pacific officials almost missed the party, since a few of their badly built bridges had already collapsed. Several times the officials had to get out of their train, trip past broken sections of track, then get on a new train and continue west. They finally made it to Promontory, where they watched a Chinese team lay the final rail connecting the two railroads. A specially made spike of gold was set in place. On the spike was the inscription “May God continue the unity of our country as this railroad unites the two great oceans of the world.”

At this moment a telegraph operator named Watson Shilling became the most important person in America. Huge crowds in cities all over the country were waiting to explode with excitement the moment the railroad was completed. Shilling sat by the tracks, ready to send out the news.

“Almost ready,” Shilling tapped out to the waiting nation. “Hats off. Prayer is being offered.”

A few minutes later, an update: “We have got done praying. The spike is about to be presented.”

Then: “All ready now, the spike will soon be driven.”

Then the Central Pacific's Leland Stanford stepped forward with a hammer. The plan was for him to tap the golden spike, just for show. He lifted the heavy hammer over his shoulder, and â¦

“He missed the spike and hit the rail,” Toponce reported. “What a howl went up! Irish, Chinese, Mexicans, and everybody yelled with delight. âHe missed it. Yee!'”

Then Thomas Durant of the Union Pacific took a try. “And he missed the spike the first time,” said Toponce. “Then everybody slapped everybody else again and yelled, âHe missed it too, yow!'”

Other witnesses didn't report Stanford and Durant swinging and missing, so we can't be sure if it really happened. We do know that somewhere in there, the telegraph operator got tired of waiting and tapped out the one-word message the entire nation was waiting for:

“Done.”

This set off wild all-day and all-night parties from New York City to San Francisco. Cannons blasted, fireworks boomed. Fire alarms and church bells rang, and people started singing and dancing and making speeches. Most Americans had nothing to do with building the transcontinental railroad, but they still took a huge amount of pride in the project. No other country had ever built anything like it. Americans sensed that their nation had just taken a major step toward becoming a great power in the world. As one Union Pacific worker at Promontory proudly put it: “The future is coming, and fast too.”

Sitting at home in Massachusetts, Theodore Judah's wife, Anna, joined the celebration in her own quiet way. “The spirit of my brave husband descended upon me,” she said, “and together we were there unseen.”

Other books

Two Blackbirds by Garry Ryan

Loud: The Complete Series (A Bad Boy Alpha Male Romance) by Claire Adams

Demons Don’t Dream by Piers Anthony

Sabrina's Vampire by Michaels, A K

Cold Copper Tears by Glen Cook

Kick Me by Paul Feig

The Eye: A Novel of Suspense by Bill Pronzini, John Lutz

Saddle Up by Victoria Vane

Just for Fun by Erin Nicholas

Land of Wolves by Johnson, Craig