Which Way to the Wild West? (5 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

B

ut even the threat of war didn't stop Americans from heading west. If it was the United States' manifest destiny to own the West, American leaders figured they might as well find out what was there. Up to that point, there were no accurate maps of most of the West. The powerful senator Thomas Hart Benton gave the job of making new maps to a young man named John Frémont (whose main qualification for mapping the West was that he was Benton's son-in-law).

ut even the threat of war didn't stop Americans from heading west. If it was the United States' manifest destiny to own the West, American leaders figured they might as well find out what was there. Up to that point, there were no accurate maps of most of the West. The powerful senator Thomas Hart Benton gave the job of making new maps to a young man named John Frémont (whose main qualification for mapping the West was that he was Benton's son-in-law).

Frémont put together a team of explorers, including a German mapmaker named Charles Preuss. Preuss was not what you would call an outdoorsman. The moment the crew set out from St. Louis, he began whining about the aches in his body from riding on horses and sleeping on hard ground. Some of his early journal entries tell of other complaints:

“Weather good. Food bad.”

“I wish I were in Washington with my old girl.”

“I wish I had a drink.”

When the men killed an ox for food, Preuss wrote these entries in his journal:

June 12:

Some of the men tried to eat the liver raw. I was

satisfied with bread and coffee; I am not yet so hungry that

I would gulp down very fresh meat, which is repulsive to me.

Tomorrow, to be sure, it will taste excellent.

Some of the men tried to eat the liver raw. I was

satisfied with bread and coffee; I am not yet so hungry that

I would gulp down very fresh meat, which is repulsive to me.

Tomorrow, to be sure, it will taste excellent.

June 13:

It did not taste excellent.

It did not taste excellent.

And speaking of food, Preuss noted, when they did get some decent meat, the cook always ruined it. “That fool had packed neither sugar nor salt nor pepper,” wrote Pruess. “What good is the best food stuff if one cannot prepare it properly?”

As they headed farther west that summer, it got unbearably hot and buggy. Then there were endless and exhausting climbs into the Rocky Mountains. “No supper, no breakfast, little or no sleep,” Preuss wrote. “Who can enjoy climbing a mountain under these circumstances?”

He was particularly annoyed that Frémont kept stopping to collect samples of rocks and plants. “That fellow knows nothing about mineralogy or botany,” wrote Preuss. “Yet he collects every trifle ⦠. Let him collect as much as he wantsâif he would only not make us wait for our meal ⦠. Oh, you American blockheads!”

Preuss's only kind words were for a small group of Indians who saved him when he got lost in the desert and was dying of hunger. “I walked straight up to them, sat down among them, and gave them to understand that I was hungry,” he wrote. “They immediately served me acorns, some of which I ate, and others I put in my pocket. When they saw this, they themselves filled both my pockets.”

He may have been miserable, but Preuss was a very good mapmaker (and he needed the job to support his family). Suffering through three long journeys across the West in the 1840s, Preuss produced the most accurate maps yet of the region. The maps were published along with Frémont's journalsâwhich Frémont's wife, Jesse, rewrote for him when he got home.

These maps and journals became huge best sellers. They got Americans even more interested in all that land to the west.

T

he idea of moving to Oregon was especially exciting. “The Oregon fever is raging in almost every part of the union,” reported one newspaper.

he idea of moving to Oregon was especially exciting. “The Oregon fever is raging in almost every part of the union,” reported one newspaper.

It was hard for easterners to resist the fever when they heard tales of Oregon's mild climate and fertile soil. One farmer listened to a land promoter trying to persuade people to move to Oregon:

“They do say, gentlemen, they do say that out in Oregon the pigs are running about under the great acorn trees, round and fat, and already cooked, with knives and forks sticking in them so that you can cut off a slice whenever you are hungry.”

No one really believed that (let's hope), but thousands of families were convinced that they could build a better life in Oregon. Actually, by reading diaries from that time, we see that it was almost always the husbands who made the decision to move west. Wives were often more reluctant

to leave their friends and family behind, knowing they would probably never see each other again. “Dr. Wilson has determined to go,” wrote a young woman named Margaret Wilson. “I am going with him, as there is no other alternative.”

to leave their friends and family behind, knowing they would probably never see each other again. “Dr. Wilson has determined to go,” wrote a young woman named Margaret Wilson. “I am going with him, as there is no other alternative.”

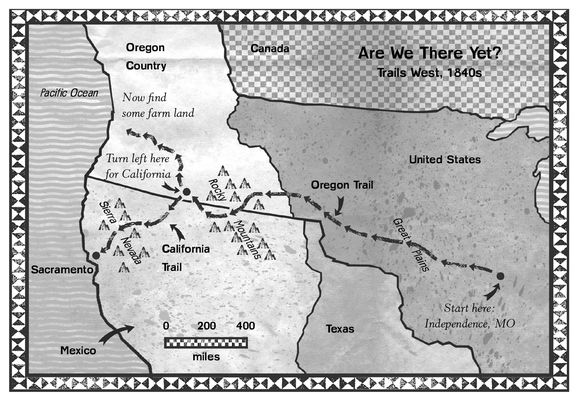

Once the decision was made, the next step was to pack up a wagon and head to Missouri, where the Oregon Trail began. There you could stock up on important supplies like flour, bacon, sugar, coffee, and barrels of water. And you could team up with other families and hire a guide, usually an out-of-work mountain man. Mountain men had killed off most of the beavers in the West, but now they found new careers guiding families along the Oregon Trail.

E

ven with an expert guide, this was an exhausting and dangerous 2,400-mile trip. Dragged forward by oxen, wagons rocked along at a top speed of two miles an hour. Men kept busy herding the families' farm animals, repairing the wagons, and hunting for dinner. Women worked even harder, getting up at four a.m. to start breakfast, then working all day and late into the nightâcooking, cleaning, washing and mending clothes, taking care of young children â¦

ven with an expert guide, this was an exhausting and dangerous 2,400-mile trip. Dragged forward by oxen, wagons rocked along at a top speed of two miles an hour. Men kept busy herding the families' farm animals, repairing the wagons, and hunting for dinner. Women worked even harder, getting up at four a.m. to start breakfast, then working all day and late into the nightâcooking, cleaning, washing and mending clothes, taking care of young children â¦

Bigger kids walked alongside the wagon, lightening the load a little for the poor oxen. As they walked, children had the key job of collecting buffalo chips, which were used for cooking fuel. The chips burned quickly, so they had to gather huge piles of them for every meal.

Once they were out on what seemed like the endless Great Plains, many families started wishing they had packed a bit lighter. They wondered,

Do we really need this heavy kitchen table? Wouldn't we move a bit faster without these extra chairs?

Desperate to speed up their journey, they started tossing stuff out the backs of their wagons, littering the road to Oregon with a trail of furniture, mirrors, tools, stoves, beds, and clothing.

Do we really need this heavy kitchen table? Wouldn't we move a bit faster without these extra chairs?

Desperate to speed up their journey, they started tossing stuff out the backs of their wagons, littering the road to Oregon with a trail of furniture, mirrors, tools, stoves, beds, and clothing.

Aside from simply being sick of traveling, families had another reason for wanting to move quickly. “During the entire trip Indians were a source of anxiety, we being never sure of their friendship,” explained one traveler. It was a relief to discover that Native Americans were much more interested in trading with travelers than attacking them. The two main causes of death for early Oregon Trail travelers

might surprise you. Number one: gun accidents. Number two: drowning while trying to cross rivers.

might surprise you. Number one: gun accidents. Number two: drowning while trying to cross rivers.

As more and more travelers crowded the trail, a new problem became clearâto both eyes and noses. The route was dotted with countless mounds of human waste. “The stench is sometimes almost unendurable,” said a traveler named Charlotte Pengra. These stinky piles polluted water supplies, helping to spread deadly diseases. Disease soon became the deadliest danger on the Oregon Trail. Just ask Catherine Sager.

C

atherine Sager was nine years old when she and her father, pregnant mother, and five brothers and sisters set out on the Oregon Trail in the spring of 1844. Soon after starting, her mother gave birth to a baby girl. Then they got right back on the road.

atherine Sager was nine years old when she and her father, pregnant mother, and five brothers and sisters set out on the Oregon Trail in the spring of 1844. Soon after starting, her mother gave birth to a baby girl. Then they got right back on the road.

Catherine was expecting a tough journey, but she was surprised by the first major problem the family faced: seasickness. “The motion of the wagon made us all sick,” she remembered. “It was weeks before we got used to the seasick motion.”

Once they got used to the bouncing, the Sager kids came up with travel games, like jumping in and out of the wagon while it was moving. It was lots of funâuntil one day in August:

“When performing this feat that afternoon my dress caught ⦠and I was thrown under the wagon wheels, both of which passed over me, badly crushing the left leg, before father could stop the oxen.”

Catherine Sager

Catherine's father leaped down and scooped up his daughter. “My dear child,” he cried, “your leg is broken all to pieces!” A doctor from another wagon put her leg in a cast. Then they got right back on the road.

From then on Catherine rode in the wagon, or walked alongside on crutches (that shows you how slow the oxen wereâshe could keep up on crutches!). Anyway, this turned out to be the good part of the trip. Catherine's father soon caught a fever, grew weaker and weaker, and died. He was buried along the trail. Less than a month later, her mother got sick (she had never fully recovered from a difficult childbirth). She died and was also buried by the trail.

“So in twenty-six days we became orphans,” Catherine wrote. “Seven children of us, the oldest fourteen and the youngest a babe.” Too far west to turn back, they had no choice but to get back in their wagon and continue on to Oregon. Other families on the trail helped the Sager children prepare food and take care of their baby sister. All seven Sager kids made it to Oregon, where they were dropped off at

the home of Narcissa and Marcus Whitmanâthe missionaries who had traveled to Oregon almost ten years before.

the home of Narcissa and Marcus Whitmanâthe missionaries who had traveled to Oregon almost ten years before.

“She spoke kindly to us as she came up,” Catherine said of her first meeting with Narcissa Whitman. “But like frightened things we ran behind the cart, peeping shyly around at her.”

Whitman asked the boys why they were crying. They told her.

“Poor boys, no wonder you weep!” she said.

The Whitmans took in all seven Sagers. The children found Narcissa Whitman kind and generous, though very strict. Catherine's sister Matilda explained how Narcissa ran her house: “She would point to one of us, then point to the dishes or the broom, and we would instantly get busy.”

A

mericans continued moving west for all the usual reasonsâthe desire for land, the hunger for adventure, the need to find work or escape debt. A twenty-one-year-old teacher named John Bidwell had a slightly stranger motive. When he came home to his Missouri farm after summer vacation, some other guy was living there! The guy claimed the farm was his nowâand did so while pointing a shotgun at Bidwell's chest.

mericans continued moving west for all the usual reasonsâthe desire for land, the hunger for adventure, the need to find work or escape debt. A twenty-one-year-old teacher named John Bidwell had a slightly stranger motive. When he came home to his Missouri farm after summer vacation, some other guy was living there! The guy claimed the farm was his nowâand did so while pointing a shotgun at Bidwell's chest.

That's when Bidwell decided to move west.

He knew about Oregon, of course, but he had also heard interesting stories of California, a vast land of mountains and grassy valleys in northern Mexico. There was only one problem. “Our ignorance of the route was complete,” Bidwell confessed. “We knew that California lay west, and that was the extent of our knowledge.”

He was right about the west part. California stretched along the western coast of North America for eight hundred miles. Growing up in California in the early 1800s, Guadalupe Vallejo spent his childhood riding the open spaces between ranches and towns. “We traveled as much as possible on horseback,” he said. “Every one seemed to live outdoors.”

“We were the pioneers of the Pacific coast, building towns and missions while General Washington was carrying on the war of the Revolution.”

Guadalupe Vallejo

Vallejo's history was correct: the Spanish had founded San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco in the late 1700s. Vallejo lived near San Francisco Bay, enjoying parties, dances, feasts, bullfights, and rodeos. He even liked the grizzly bears. “The young Spanish gentlemen often rode out on moonlit nights to lasso these bears,” Vallejo said, “and then they would drag them through the village street, and past the houses of their friends.”

Of course, there's always another side to the story. The reason Spanish families had so much time for fun was that they forced Native Americans to do most of the hard work of running ranches and farms.

By the 1840s California was home to about 7,000 Spanish settlers and 150,000 Native Americansâand a growing number of Americans. The American teacher John Bidwell made it to California, barely surviving tornadoes and hailstorms, flooding rivers, and torturous thirst. (At one point in the desert, the only water he could find was so muddy and smelly, he had to brew it into coffee before his horses would drink it.)

Bidwell's route to California became known as the California Trail. And as Americans started traveling this trail, they found all the dreaded dangers of the Oregon Trail, with one bonus danger: the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Other books

A Cure for Madness by Jodi McIsaac

Mostly Dead (Barely Alive #3) by Bonnie R. Paulson

Digital Devil Story: Reincarnation of the Goddess by Aya Nishitani

Ford: The Dudnik Circle Book 1 by Esther E. Schmidt

Godslayer by Jacqueline Carey

Paint the Wind by Pam Munoz Ryan

Dare to Bear (Book 1 Trail Guardians Series) by Julian, Christine

The Gorgon by Kathryn Le Veque

Quillblade by Ben Chandler

On the Auction Block by Ashley Zacharias