Which Way to the Wild West? (3 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

F

ights with Native Americans were another danger, since some tribes did not welcome the sight of outsiders trapping animals in their territory. But more often, mountain men traded with Native Americans, learning from them how to hunt, travel, and survive in the snowy mountains. Mountain men began dressing like Indians, and they considered it a great compliment to be mistaken for one of them.

ights with Native Americans were another danger, since some tribes did not welcome the sight of outsiders trapping animals in their territory. But more often, mountain men traded with Native Americans, learning from them how to hunt, travel, and survive in the snowy mountains. Mountain men began dressing like Indians, and they considered it a great compliment to be mistaken for one of them.

James Beckwourth did more than dress like an Indianâhe moved in with them. Invited to join a group of Crow Indians, Beckwourth learned the Crow language, got married, and even fought in the Crow's battles against rival tribes.

When Beckwourth's mountain men friends didn't see him for a

few years, they figured he must have died somewhere in the wilderness. This led to a strange scene at Fort Clark, a trading post in what is now North Dakota.

few years, they figured he must have died somewhere in the wilderness. This led to a strange scene at Fort Clark, a trading post in what is now North Dakota.

Beckwourth and some Crow friends showed up with a stack of beaver pelts to trade. Of course, they were dressed as Crows and speaking the Crow language. One of the Crow men stepped up to the counter and asked the American clerks for

“be-has-i-pe-hish-a.”

“be-has-i-pe-hish-a.”

The puzzled clerks just stood there.

“

Be-has-i-pe-hish-a,

” said the Crow.

Be-has-i-pe-hish-a,

” said the Crow.

More confused silence.

Then Beckwourth stepped up and said, “Gentlemen, that Indian wants scarlet cloth.”

“If a bombshell had exploded in the fort they could not have been more astonished,” Beckwourth remembered. This dialogue followed:

Clerk:

Ah, you speak English! Where did you learn it?

Ah, you speak English! Where did you learn it?

Beckwourth:

With the white man.

With the white man.

Clerk:

How long were you with the whites?

How long were you with the whites?

Beckwourth:

More than twenty years.

More than twenty years.

Clerk:

Where did you live with them?

Where did you live with them?

Beckwourth:

In St. Louis.

In St. Louis.

Clerk:

If you have lived twenty years in St. Louis, I'll swear you are no Crow.

If you have lived twenty years in St. Louis, I'll swear you are no Crow.

Beckwourth:

No, I am not.

No, I am not.

Clerk:

Then what may be your name?

Then what may be your name?

Beckwourth:

My name in English is James Beckwourth.

My name in English is James Beckwourth.

Clerk:

Good heavens! Why, I have heard your name mentioned a thousand times. You were supposed to be dead.

Good heavens! Why, I have heard your name mentioned a thousand times. You were supposed to be dead.

Beckwourth:

I am not dead, as you see.

I am not dead, as you see.

James Beckwourth spent another six years with the Crows, becoming a high-ranking chief. And all the while, stories about Beckwourth and other mountain men continued to excite Americans about new opportunities in the West.

T

his interest in the West gave a nineteen-year-old named David Meriwether what seemed like a good idea. He would set up a trading route connecting American towns in Missouri with settlements in northern Mexico, hundreds of miles to the southwest.

his interest in the West gave a nineteen-year-old named David Meriwether what seemed like a good idea. He would set up a trading route connecting American towns in Missouri with settlements in northern Mexico, hundreds of miles to the southwest.

“I had learned from the Indians that there was a good country from Missouri to the Mexican settlements for a road,” Meriwether said. The key would be to find a route that wagons could use to transport goods back and forth. In June 1820, Meriwether set out to find the route.

Traveling with him was an African American teenager named Alfred. (Was Alfred his friend? His slave? Both? Meriwether doesn't say.) The problem was, Mexico was Spanish territory, and Spanish leaders didn't allow Americans on their land. Soon after crossing into Mexico, Meriwether and Alfred were arrested by Spanish soldiers.

The soldiers forced the Americans to march through the scorching desert toward the town of Santa Fe. Meriwether's feet were soon sliced open by rocks and cactus needles. “This was the most miserable

day of my life,” he remembered, “for I felt as though I would as soon die as live.”

day of my life,” he remembered, “for I felt as though I would as soon die as live.”

Unable to bear the pain of another step, Meriwether dropped to the sand and refused to move. A Spanish soldier raised his sword over Meriwether's head.

“Davy, get up and come along or they will kill you,” Alfred urged.

“Let them kill me; I will not walk another step farther.”

David Meriwether Alfred

Alfred somehow talked the soldiers into letting Meriwether ride a mule. When they finally arrived in Santa Fe, the Americans were thrown into separate flea-filled jail cells. Meriwether was starving by now, so when a guard finally brought in some food he was thrilledâuntil he tasted it. “About night my jailor came with a small earthen

bowl with boiled frijoles, or red beans,” he said “I found it so strongly seasoned with pepper that I could not eat it.”

bowl with boiled frijoles, or red beans,” he said “I found it so strongly seasoned with pepper that I could not eat it.”

Boy, when things go wrong ⦠. Anyway, after swearing to go back to American territory and stay there, Meriwether and Alfred were let out of jail.

“I never expected to see you again,” Alfred said when they met in the street outside the prison. They quickly headed back to Missouri.

Just a year later, in 1821, Mexicans kicked out the Spanish rulers and declared themselves independent. This changed everything, because Mexican leaders welcomed American travelers and traders. And the route that Alfred and Meriwether had traveled soon became a busy trading route known as the Santa Fe Trail.

Even without angry soldiers to deal with, this was a dangerous eight-hundred-mile trip. One of the first groups to travel the trail found this out when they decided to take a shortcut through the Cimarron Desert. They soon ran out of water and were close to dying of thirst when they saw a buffalo walking toward them. They shot the animal, cut it openâand shouted with joy to find its stomach filled with water. The men gulped down the warm liquid and got back on the trail to Santa Fe.

What's that you say? You like the idea of moving west, but you don't feel like wrestling grizzly bears or drinking buffalo puke? Then you might consider settling on a plot of fertile land in the northern region of Mexico called Tejas.

W

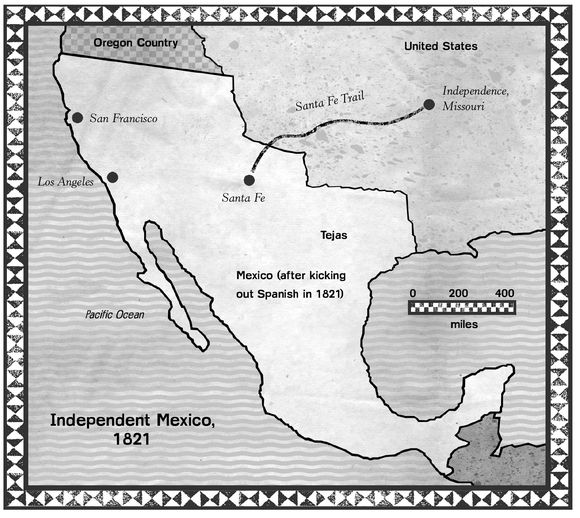

hen Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, the new nation looked like this:

hen Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, the new nation looked like this:

Look at that large area in northern Mexico marked

Tejas,

or Texas, as Americans called it. Very few people lived there, and the Mexican government was looking for settlers. So they were pleased when a twenty-nine-year-old man from Missouri named Stephen Austin led about three hundred American families to Texas in 1822.

Tejas,

or Texas, as Americans called it. Very few people lived there, and the Mexican government was looking for settlers. So they were pleased when a twenty-nine-year-old man from Missouri named Stephen Austin led about three hundred American families to Texas in 1822.

Stories about sunny Texas soon spread. You could buy huge chunks of good land for a small fraction of the price of farmland in the United States. Thousands of Americans packed up their stuff and scratched “G.T.T.” on the doors of their cabins. Everyone knew what that meant: “Gone to Texas.”

Settlers in Texas were supposed to promise loyalty to the Mexican government and obey Mexican laws, including a ban on slavery. But the Mexican capital, Mexico City, was 1,200 miles to the south. Mexican officials simply had no way of controlling what people did in Texas. As a result, American settlers basically governed themselves. They liked it that way.

By 1830 there were more than 20,000 Americans in Texas. This was beginning to worry Mexican leadersâthey felt they were losing control of their land to the Americans (or, as they called them, “

los Yanquis

”). The Mexican president, Antonio López de Santa Anna, decided to get tough with the Americans. He declared he would cut immigration, collect taxes, and enforce Mexican law. And he'd use force to do it, if necessary.

los Yanquis

”). The Mexican president, Antonio López de Santa Anna, decided to get tough with the Americans. He declared he would cut immigration, collect taxes, and enforce Mexican law. And he'd use force to do it, if necessary.

But by now Texans were used to independence. They reacted angrily to Santa Anna's threats. “Every man in Texas is called upon to take up arms in defense of his country and his rights,” declared Stephen Austin.

True, Texans weren't actually in their country. But they felt like it was their home. They were ready to fight for it.

I

n 1835 Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law to Texas to teach the Americans a lesson by seizing control of the town of San Antonio. The brother-in-law didn't really know how to seize towns. He ended up surrendering San Antonio to the Texans.

n 1835 Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law to Texas to teach the Americans a lesson by seizing control of the town of San Antonio. The brother-in-law didn't really know how to seize towns. He ended up surrendering San Antonio to the Texans.

Now Santa Anna was furious. Pronouncing himself a military genius (he called himself “the Napoleon of the West”), Santa Anna vowed to personally crush the rebels.

“The great problem I had to solve was to reconquer Texas and to accomplish this in the shortest time possible.”

He even threatened to march all the way to the White House while he was at it. But first things first: Santa Anna headed toward Texas, his personal wagons loaded with silverware, china plates, and a silver chamber pot. He seemed less worried about the comfort of his four thousand soldiers. Short on food, tents, and medicine, many of the men starved or froze to death in blizzards as the army stumbled north.

Antonio López de Santa Anna

In San Antonio, meanwhile, Texas soldiers gathered in an old Spanish mission known as the Alamo. This was a crumbling church, with a courtyard of about two and a half acres, all surrounded by tall stone walls.

When Santa Anna and his soldiers finally made it to San Antonio in February 1836, they quickly surrounded the Alamo. Trapped inside were about 180 volunteer soldiers, both Americans and Tejanos, or Mexicans from Texas. Many of the soldiers' families were stuck in there too.

William Travis, one of the leaders of the Texas army, dashed off a desperate note addressed “To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World”:

“FELLOW CITIZENS AND COMPATRIOTSâI am besieged, by a thousand or more Mexicans under Santa Anna ⦠. The enemy has demanded a surrender ⦠. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, and our flag still waves proudly from the wallsâI shall never surrender or retreat.”

Just a few days later, before sunrise on the chilly morning of March 6, a Texan named John Baugh looked over the walls and saw Mexican soldiers charging toward the Alamo.

Baugh broke the morning silence with the shout: “Colonel Travis! The Mexicans are coming!”

Other books

And Be a Villain by Rex Stout

Crashed (Entangled Indulgence) by Sherilee Gray

TFT 01 Beauty and the Beast by K.M. Shea

Shooting Stars by Stefan Zweig

Find This Woman by Richard S. Prather

Mimesis by Erich Auerbach,Edward W. Said,Willard R. Trask

Dusty: Reflections of Wrestling's American Dream by Rhodes, Dusty, Brody, Howard

The Long Earth by Terry Pratchett, Stephen Baxter

Doomsday Warrior 05 - America’s Last Declaration by Ryder Stacy