Which Way to the Wild West? (19 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

F

rom his homeland in Oregon, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce watched the fall of the powerful Plains Indians. The message was clear: Indians could win battles against American soldiers. But even the most powerful groups could not win wars against the United States.

rom his homeland in Oregon, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce watched the fall of the powerful Plains Indians. The message was clear: Indians could win battles against American soldiers. But even the most powerful groups could not win wars against the United States.

Joseph was determined to help the Nez Perce hold on to their traditional territory in Oregon's Wallowa Valley. He had sworn to his dying father that he would never give up this land.

“You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home,” Joseph's father told him. “My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father's body. Never sell the bones of your father and mother.”

“I pressed my father's hand and told him I would protect his grave with my life,” Joseph said.

This promise put Joseph in an impossible position in 1877. Actually, it wasn't the promise that caused troubleâit was that American settlers were moving onto Nez Perce land.

How was Joseph supposed to defend this land once the United States decided to take it?

In April 1877, General Oliver O. Howard left his headquarters in Portland, Oregon, and headed east. He had new orders: Clear the Nez Perce off their land and move them to a reservation in Idaho. Privately, Howard sympathized with the Indians, telling friends: “It is a great mistake to take from Joseph and his band of Nez Perce Indians that valley.” But Howard had his orders. He continued toward the Wallowa Valley to deliver the government's demand.

I

t was the same old story. Gold had been found on the Nez Perce land, and settlers raced in. They started putting up cabins, fencing in farms, stealing Nez Perce cattle. Both sides were ready to fight for the land. Hoping to avoid another costly Indian war, the government offered the Nez Perce land on a reservation in nearby Idaho. It wasn't really an offer.

t was the same old story. Gold had been found on the Nez Perce land, and settlers raced in. They started putting up cabins, fencing in farms, stealing Nez Perce cattle. Both sides were ready to fight for the land. Hoping to avoid another costly Indian war, the government offered the Nez Perce land on a reservation in nearby Idaho. It wasn't really an offer.

The Nez Perce realized this when General Oliver Howard showed up in May 1877. Howard told them to pack up and leave the Wallowa Valley. If they didn't get moving, Howard warned, the army would come and give them a shove.

Joseph and the other chiefs told Howard they had never agreed to be moved from their homeland. “Chief Toohoolhoolzote stood up to talk for the Indians,” remembered a young Nez Perce named Yellow Wolf. “He told how the land always belonged to the Indians.” This led to an angry argument with Howard:

Howard:

You know very well that the government has set apart a reservation, and that the Indians must go on it.

You know very well that the government has set apart a reservation, and that the Indians must go on it.

Toohoolhoolzote:

Who are you to tell me what to do? What person pretends to divide the land?

Who are you to tell me what to do? What person pretends to divide the land?

Howard:

I am that man. I stand here for the president. My orders are plain and will be executed.

I am that man. I stand here for the president. My orders are plain and will be executed.

Toohoolhoolzote:

We came from the earth, and our bodies must go back to the earth, our mother.

We came from the earth, and our bodies must go back to the earth, our mother.

Howard:

I don't want to offend your religion, but you must talk about practicable things. Twenty times over I hear that the earth is your mother ⦠. I want to hear no more, but come to business at once.

I don't want to offend your religion, but you must talk about practicable things. Twenty times over I hear that the earth is your mother ⦠. I want to hear no more, but come to business at once.

Toohoolhoolzote:

Who can tell me what I must do in my own country? Are you the Great Spirit? Did you make the world? Did you make the sun?

Who can tell me what I must do in my own country? Are you the Great Spirit? Did you make the world? Did you make the sun?

Howard finally got sick of arguing. He told the Nez Perce they had thirty days to leave their land.

“Why are you in such a hurry?” Joseph asked. “I cannot get ready to move in thirty days.” He explained that they would need more time to gather their animals and collect supplies for the coming winter.

“If you let the time run over one day,” Howard warned, “the soldiers will be there to drive you onto the reservation.”

Howard's threat sparked a fierce debate among the Nez Perce. “I did not want bloodshed,” Joseph said. “I did not want my people killed. I did not want anybody killed.” He argued that it would be better to move than to see their people killed in a war that could never be won.

But many of the younger chiefs and warriors vowed to stay and fight. “Toohoolhoolzote talked for war,” Joseph remembered, “and made many of my young men willing to fight rather than be driven like dogs from the land where they were born.”

While Joseph made preparations to leave, a group of young warriors left the village at night, marched to nearby cabins, and killed four settlers. “I would have given my own life if I could have undone the killing of white men by my people,” Joseph said.

Now, he knew, General Howard would be sending his soldiers to fight the Nez Perce. Now there was no way to avoid war.

“I

t was just like two bulldogs meeting,” Yellow Wolf said of the moment he and other Nez Perce warriors slammed into the American soldiers. “We drove them back across the mountain, down to near the town they came from.”

t was just like two bulldogs meeting,” Yellow Wolf said of the moment he and other Nez Perce warriors slammed into the American soldiers. “We drove them back across the mountain, down to near the town they came from.”

Thirty-three Americans were killed in this quick battle. “I never went up against anything like the Nez Perces in all my life,” said one of the surviving soldiers.

The young Nez Perce warriors celebrated. But Joseph and the other chiefs knew Howard would be back soon, and with a much bigger army. With only about 150 warriors, the Nez Perce could not simply wait here to be attacked. Their only choice was to start moving.

“From that time, the Nez Perce had no more rest,” Yellow Wolf remembered.

About seven hundred Nez Perce men, women, and children quickly packed everything they and their animals could carry. Then they headed east toward the open spaces of Montana. There they hoped to meet up with the Crow Indians, old allies of theirs.

When he saw the Nez Perce moving, General Howard and his

five hundred soldiers set off to catch them. They chased the Nez Perce out of Oregon and into the rugged Bitterroot Mountains of Idaho. As news of the chase spread, people in nearby towns panicked and locked themselves in their cabins (parents in one town locked their children in the vault of the local bank).

five hundred soldiers set off to catch them. They chased the Nez Perce out of Oregon and into the rugged Bitterroot Mountains of Idaho. As news of the chase spread, people in nearby towns panicked and locked themselves in their cabins (parents in one town locked their children in the vault of the local bank).

In western Montana a small group of soldiers gathered to try to block the path of the oncoming Nez Perce. After laying logs across the road, the men declared: “You cannot get by us.”

“We are going by you without fighting if you will let us,” Joseph answered. “But we are going by you, anyhow.”

Suddenly feeling extremely outnumbered, the soldiers got out of the way. And the chase continued across Montana, then south back into Idaho, and east into Wyoming. “We rode on, always watching for enemies,” Yellow Wolf said. As one of the Nez Perce scouts, he had the vital job of watching for Howard's army. Only during rare moments of rest did he allow himself to think about home:

“Thoughts came of the Wallowa where I grew up. Of my own country when only Indians were there. Of tepees along the bending river. Of the blue, clear lake, wide meadows with horse and cattle herds.”

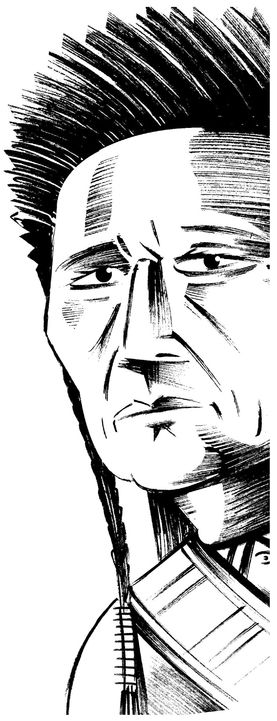

Yellow Wolf

Where was General Howard's army meanwhile? That's what the entire country was wondering. By now Americans everywhere were following the amazing chase in their newspapers. An increasingly irritated General Sherman sent Howard telegrams with orders such as: “That force of yours should pursue the Nez Perce to the death.”

A

s Howard pushed his men harder, exhausted soldiers wore through their boots and had to tie rags around their bloody feet. They shivered through rainy nights, unable to start fires with only wet buffalo chips for fuel. And all they had to eat was rotting pork and biscuits so hard that they had to be soaked overnight before they were soft enough to chew.

s Howard pushed his men harder, exhausted soldiers wore through their boots and had to tie rags around their bloody feet. They shivered through rainy nights, unable to start fires with only wet buffalo chips for fuel. And all they had to eat was rotting pork and biscuits so hard that they had to be soaked overnight before they were soft enough to chew.

The Nez Perce were running out of food too. Some of the older men and women were getting too weak and tired to continue. When they couldn't take another step, they asked to be wrapped in blankets and set in the shade. Everyone knew they would die there.

By late August the Nez Perce finally met up with their Crow allies in Montana. It was a disappointing reunion. The Crows explained that they had seen what had just happened to the Lakota and Cheyenne after Little Bighorn. They were not willing to take sides against the United States.

All alone now, and far from home, the Nez Perce had one last chanceâthey could make a run for Canada. If they could get across the border, they might be able to team up with Sitting Bull and the Lakota who had followed him north.

The Nez Perce hurried in that direction, reaching the Bear Paw Mountains in late September. After traveling more than 1,700 miles

in three months, they were just two days from the Canadian border. “We knew General Howard was more than two suns back on our trail,” Yellow Wolf said. In fact, warriors started calling Howard “General Day-and-a-Half-Behind.”

in three months, they were just two days from the Canadian border. “We knew General Howard was more than two suns back on our trail,” Yellow Wolf said. In fact, warriors started calling Howard “General Day-and-a-Half-Behind.”

What they didn't know was that another American army, commanded by Colonel Nelson Miles, was racing toward their camp from the east. As Joseph and the Nez Perce rested for their final march to Canada, Miles and his army were less than fifteen miles away.

T

he Nez Perce were packing up for their last march north when scouts came galloping into camp, shouting:

he Nez Perce were packing up for their last march north when scouts came galloping into camp, shouting:

“Soldiers! Soldiers!”

“Enemies right on us!”

Moments later Colonel Miles and his six hundred soldiers charged into camp.

“My little daughter, twelve years old, was with me,” Joseph remembered. “I gave her a rope, and told her to catch a horse.”

Joseph's daughter and many others were able to get away while Joseph and the warriors tried to fight off the attack. “Six of my men were killed in one spot near me,” Joseph said. “I called my men to drive them back. We fought at close range, not more than twenty steps apart.”

Many of the best Nez Perce warriors died in a bloody, daylong battle. Miles had the camp surrounded by nightfall. The next morning, as snow started falling, he began blasting shells into camp. The Nez Perce dug holes in the snow for protection from the bombs and the cold. But they were nearly out of food.

After five days of this, Colonel Miles demanded surrender. “If you will come out and give up your arms,” he said, “I will spare your lives and send you to your reservation.”

Some of the surviving chiefs wanted to fight on to the death. But Joseph was desperate to save as many lives as he could. “I am tired of fighting,” he told the Americans.

“It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they areâperhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

Chief Joseph

Joseph demanded that the Nez Perce be allowed to travel in safety to the reservation in Idaho. Miles agreed. The men shook hands.

Then Sherman heard about the dealâand threw another fit. “The Indians are prisoners, and their wishes should not be consulted,” he told Miles.

Sherman wanted to send a chilling signal to any other Indian groups that might be thinking about standing up to the United States. He ordered the Nez Perce taken on another long journey, one thousand miles east and south by riverboat and train. Joseph and the Nez Perce were dumped off on a hot and buggy piece of reservation land in Indian Territoryâtoday's Oklahoma.

The government told them:

Now you can learn to live like civilized people.

Now you can learn to live like civilized people.

Other books

Cat and Mouse by William Campbell Gault

Lady Amelia's Secret Lover by Victoria Alexander

Irish Magic by Caitlin Ricci

Highland Moon Sifter (a Highland Sorcery novel) by Autrey, Clover

Exposing the Real Che Guevara by Humberto Fontova

Life Is a Serious Business by Anne Butler

Alex’s Adventures in Numberland by Bellos, Alex

Cradle Of Secrets by Lisa Mondello