Which Way to the Wild West? (18 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

T

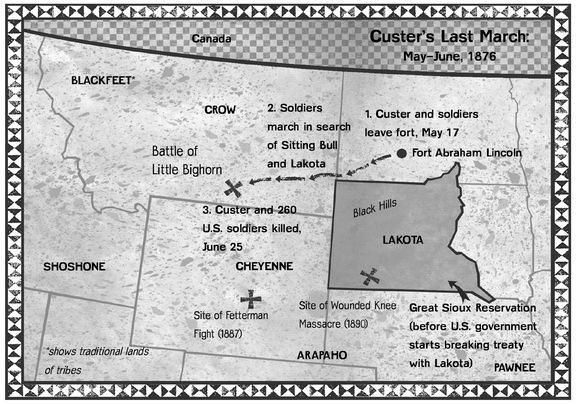

. P. Eagan and the rest of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh Cavalry rode away from Fort Abraham Lincoln, off to find Sitting Bull and drive him onto a reservation. Everyone knew it would be a risky job. “The wives and children of the soldiers lined the road,” Elizabeth Custer remembered. “Mothers, with streaming eyes, held their little ones out at arm's length for one last look at the departing father.”

. P. Eagan and the rest of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh Cavalry rode away from Fort Abraham Lincoln, off to find Sitting Bull and drive him onto a reservation. Everyone knew it would be a risky job. “The wives and children of the soldiers lined the road,” Elizabeth Custer remembered. “Mothers, with streaming eyes, held their little ones out at arm's length for one last look at the departing father.”

Then the soldiers marched away. All the families could do was stay in the fort and wait for news.

“We have not seen any signs of Indians thus far,” Custer wrote to his wife on May 20. He added that he and his brother, an officer in his unit, were having a wonderful time. “Tom and I have fried onions at breakfast and dinner,” he wrote, “and raw onions for lunch!”

“They both took advantage of their first absence from home to partake of their favorite vegetable,” Elizabeth noted. “Onions were permitted at our table, but after indulging in them they found themselves severely let alone, and that they did not enjoy.”

Custer sent an update on June 21: his scouts had found a fresh trail left by a large group of Indians. “I feel hopeful of accomplishing great results,” he wrote.

“I have but a few moments to write,” he added the next day. “We move at twelve, and I have my hands full of preparations ⦠. Do not be anxious about me ⦠. I hope to have a good report to send you by the next mail.”

Two days later Custer stood on a hilltop looking through binoculars toward a huge Indian camp along the banks of the winding Little Bighorn River.

“The largest Indian camp on the North American continent is ahead and I am going to attack it.”

George Armstrong Custer

Determined to surprise his enemy, Custer decided to attack without taking time to study the geography or find out how many warriors he might be facing. He divided his forces, leading 210 men toward the camp himself. Another force, led by Major Marcus Reno, approached the camp from a different direction.

“We'll find enough Sioux to keep us fighting two or three days,” predicted a Crow Indian who was working as a scout for Custer.

Custer shook his head. “I guess we'll get through them in one day,” he said.

“I

t was somewhere past the middle of the afternoon, and all of us were having a good time,” remembered a Cheyenne woman of the moment before Custer's attack on June 25, 1876.

t was somewhere past the middle of the afternoon, and all of us were having a good time,” remembered a Cheyenne woman of the moment before Custer's attack on June 25, 1876.

More than six thousand Lakota, Cheyenne, and other Indian alliesâincluding about two thousand warriorsâwere camped along the Little Bighorn. They knew the Americans were out there somewhere. “I was thirteen years old and not very big for my age,” remembered Black Elk, “but I thought I should have to be a man anyway.” He was swimming with friends in the Little Bighorn when he heard sudden shouts:

“The chargers are coming!”

“They are charging!”

Black Elk ran to his family's lodge for his rifle. His friend Iron Hawk, who was fourteen, also prepared for battle. “I was so shaky that it took me a long time to braid an eagle feather into my hair,” he said.

Nearby, young warriors ran into Sitting Bull's lodge, shouting that Custer was attacking. “I jumped up and stepped out,” said Sitting Bull. He saw waves of blue-coated American soldiers blasting away as they charged on horses into camp. “The bullets were like humming bees,” he said. “We thought we were whipped.”

“They came on us like a thunderbolt,” said a Lakota chief named Low Dog. “I never before nor since saw men so brave and fearless as those white warriors.”

Crazy Horse helped rally the Indian forces, shouting: “It is a good day to fight! It is a good day to die! Strong hearts, brave hearts, to the front! Weak hearts and cowards to the rear!”

“Then came the rush of the enemy,” said Billy Jackson, an American soldier who was part of Major Reno's charge. Jackson and the

other soldiers suddenly saw at least five hundred Indian warriors charging toward them. “Their shots, their war cries, the thunder of their horses' feet were deafening,” Jackson said.

other soldiers suddenly saw at least five hundred Indian warriors charging toward them. “Their shots, their war cries, the thunder of their horses' feet were deafening,” Jackson said.

Somewhere in the middle of this chaos, Custer was waving his hat and shouting, “Courage, boys, we've got them!” But now that Custer was in the Indian camp, he must have realized how badly outnumbered his soldiers were. It was too late to do anything but try to fight his way out.

Witnesses described the next few minutes as a confusing mix of swirling dust, gunshots, and shouts of pain and fury. Custer's soldiers split into smaller groups, but they were all quickly surrounded. “I think they were so scared that they didn't know what they were doing,” Black Elk said. “The shooting was quick, quick, popâpopâpop, very fast,” said a warrior named Two Moons. “We circled all around themâswirling like water round a stone.”

With no time to reload, men swung their guns at each other like clubs. They wrestled and punched and bit. Many of Custer's soldiers finally threw down their weapons. They were ready to surrender.

But the Indians kept on attacking. Sitting Bull's cousin watched Indian warriors shooting and stabbing Custer's men after they tried to surrender. “The blood of the people was hot and their hearts bad,” she said, “and they took no prisoners that day.”

M

ajor Reno and his surviving soldiersâwho had attacked from the other side of the Indian campânever saw what happened to Custer. They spent an endless night on a nearby hill, wondering why they received no messages or orders from Custer. “We felt terribly alone on that dangerous hilltop,” said a soldier named Charles Windolph. “We were a million miles from nowhere. And death was all around us.”

ajor Reno and his surviving soldiersâwho had attacked from the other side of the Indian campânever saw what happened to Custer. They spent an endless night on a nearby hill, wondering why they received no messages or orders from Custer. “We felt terribly alone on that dangerous hilltop,” said a soldier named Charles Windolph. “We were a million miles from nowhere. And death was all around us.”

When Reno's men finally made it to safety, they found out why they hadn't heard from Custer. “We had a closer view of Custer's battlefield,” one of the soldiers said. “We saw a large number of objects that looked like white boulders scattered over the field.”

As they walked nearer, they realized that these were not boulders. They were the bodies of Custer's soldiers, stripped and badly cut up. The men wept as they walked among the bodies, looking for friends.

Meanwhile, back at Fort Abraham Lincoln, the soldiers' families were suffering through the hot summer of 1876, waiting for news. “Our little group of saddened women, borne down with one common weight of anxiety, sought solace in gathering together in our house,” said Elizabeth Custer.

One day, while the women were singing to pass the time, a messenger arrived. It was an Indian named Horn Toad, one of Custer's scouts. Panting from exhaustion, he delivered the news in short sentences: “Custer killed. Whole command killed.”

Horn Toad's report was accurate. Custer and every one of the 210 men he led into battle were dead. Another fifty men from Major Reno's force had been killed. It was by far the biggest defeat the American military ever suffered in the Indian wars.

The news from Little Bighorn shocked the entire nationâcoming right at the moment Americans were celebrating the country's one hundredth birthday. General William T. Sherman promised to send more soldiers west to crush the Lakota once and for all.

B

ack at Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and the other chiefs realized they had won a historic victory. They also knew Sherman. They knew he would come after them harder than ever now, and they were not really prepared. The recent fighting had left them nearly out of ammunition.

ack at Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and the other chiefs realized they had won a historic victory. They also knew Sherman. They knew he would come after them harder than ever now, and they were not really prepared. The recent fighting had left them nearly out of ammunition.

The huge Indian camp on the Little Bighorn split up, with smaller groups marching off in different directions.

Sherman's forces went on the attack right away, just as the harsh northern plains winter began. “The worse it gets, the better,” said General George Crook, who led the attacks. “Always hunt Indians in bad weather.”

Crook pushed his shivering soldiers on long marches across the frozen plains. “I know it looks hard, but we've got to do it, and it shall be done,” he said. “If necessary we can eat our horses.”

“I'd as soon think of eating my brother,” grumbled a young officer (not loud enough for the general to hear).

All winter Crook's soldiers surprised Lakota and Cheyenne villages, capturing horses and destroying food supplies. Indians who survived the attacks were scattered in the snow without food or tents. After attacking one village, an American soldier reported: “The thermometer never got higher than 25 below ⦠. Those poor Cheyenne were out there in that weather with nothing to eat, no shelter.”

Sitting Bull led about one thousand people across the border into Canada, where they were safe from American attacks. But for those unable to escape, there was little chance of finding food on the plains. Buffalo were getting scarce now. As the winter

dragged on, groups of Indians started coming in to reservations. “I am tired of being always on the watch for troops,” explained Red Horse, a Lakota chief. “My desire is to get my family where they can sleep without being continually in the expectation of an attack.”

dragged on, groups of Indians started coming in to reservations. “I am tired of being always on the watch for troops,” explained Red Horse, a Lakota chief. “My desire is to get my family where they can sleep without being continually in the expectation of an attack.”

The Lakota teenager Black Elk felt the same way. “Wherever we went, the soldiers came to kill us,” he said of that winter. He and his family went in to a reservation. There, in May 1877, he watched the surrender of a leader he had grown up idolizing. “Crazy Horse came in with the rest of our people,” said Black Elk, “and the ponies that were only skin and bones.”

American soldiers took the famous warrior's weapon They handed him some beef and beans.

“I want this peace to last forever,” Crazy Horse said.

General Crook wanted peace too. But he had his own ideas about how to keep itâhe wanted Crazy Horse locked up.

Crazy Horse

A group of soldiers surrounded Crazy Horse. They reached for his arms.

“Don't touch me!” he yelled.

The soldiers started dragging him across the reservation. When he saw he was being taken toward a tiny jail cell, Crazy Horse yanked free and pulled out a knife.

“Kill him! Kill him!” soldiers shouted.

A soldier lunged forward and stabbed Crazy Horse with his bayonet. A few other soldiers reached for the fallen warrior.

“Let me go, my friends,” Crazy Horse said. “You have got me hurt enough.” Crazy Horse died that night. “I cried all night, and so did my father,” Black Elk said.

Other books

Ramage & the Renegades by Dudley Pope

In a Heartbeat by Elizabeth Adler

Smoke and Mirrors by Lesley Choyce

New Lands (THE CHRONICLES OF EGG) by Geoff Rodkey

Dirty Little Lies: A Men of Summer Novel by Lora Leigh

Unleashed (A Melanie Travis Mystery) by Berenson, Laurien

Cold Light of Day by Anderson, Toni

Juice by Eric Walters

The Case of the Rock 'n' Roll Dog by Martha Freeman

A Wizard's Tears by Gilbert, Craig