Understanding Sabermetrics (22 page)

Read Understanding Sabermetrics Online

Authors: Gabriel B. Costa,Michael R. Huber,John T. Saccoma

Table 9.15 Win shares, 1901 Phillies, with adjustment for Jennings and Barry

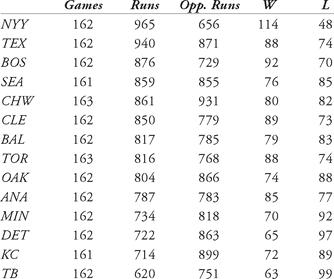

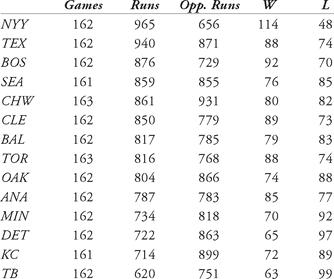

1. Here are some numbers for the American League in 1998:

a. Calculate the marginal runs for each team, offensive and defensive. Because of interleague play, the runs and opponents runs will not be the same, so use runs as the basis.

b. Give each team’s projected winning percentage and number of wins based on marginal runs. How does this compare to the Pythgorean Number that you computed in question 1(b) of chapter 6?

Consult the Internet (

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/NYM/1986.shtml

) for the 1986 New York Mets statistics. Calculate the win shares for all the players using the short-form method outlined in the following steps:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/NYM/1986.shtml

) for the 1986 New York Mets statistics. Calculate the win shares for all the players using the short-form method outlined in the following steps:

a. Calculate runs created for all the hitters

b. Make the adjustment for marginal runs and determine offensive win shares

c. calculate pitching win shares for the team

d. Find the fielding win shares for all the non-pitchers

e. Calculate total win shares for each player.

For 1986 RC, use HDG23:

A = H + BB+ HBP - CS-GIDP

B = TB + [0.29(BB + HBP-IBB)] + [0.53(SF + SH)] + [0.64(SB)] - 0.03(K)

C = AB + BB + HBP + SH + SF

Adjust the total win shares computed in the “Hard Sliders” section to reflect 48 percent offense / 35 percent pitching / 17 percent defense, making sure that the total is exactly 3 × 108 = 324. Justify your alterations in essay form.

Seventh-Inning Stretch: Non-Sabermetrical Factors

Thus far we have considered a number of measures and instruments, such as linear weights, popularized by John Thorn and Pete Palmer, and runs created and win shares, as defined by Bill James. The computations are basically simple: we take whatever statistics are available, substitute them into a formula, and get a result, generally a number. Following this comes the interpretation of the number in light of many questions, such as:

• How does this statistic compare with other players?

• Is it a cumulative measure or an aggregate measure?

• Does this number change significantly during different eras with respect to comparable players of different eras?

But in baseball, especially from a sabermetrical point of view, things are not quite this simple. While in almost every sense the numbers add up, there were (and still are) other factors which affect the national pastime, many times in negative ways. Additionally, these factors are virtually impossible to quantify. Therefore, we are forced to take a more qualitative approach, framing these factors with some observations and with questions which can never be summarily answered. To name but three, these factors include: racial discrimination, economic escalation with respect to salaries, and a decade filled with speculations and accusations of steroid use and related factors dealing with physical enhancement.

It is primarily due to the existence of these non-sabermetrical factors that a sabermetrical argument does not and cannot provide us with the same degree of certainty as a mathematical proof

.

Yet these factors do provide much fodder for conversation whenever serious baseball fans gather.

.

Yet these factors do provide much fodder for conversation whenever serious baseball fans gather.

Some non-sabermetrical factors to consider include:

• The color barrier

• Evolution of equipment and playing fields

• Technological and medical improvements

• League expansion

• Night baseball

• The Designated Hitter

• Interleague play

• Divisional play

• Wild cards

• Free agency

• The steroid controversy

• Changes in rules

Let’s look at the last one, changes in rules, and let’s consider how the home run has been affected. There was a time when present ground-rule doubles were counted as home runs; that is, batted balls which bounced into the stands were ruled to be home runs. On the other hand, baseballs which cleared the fence in fair territory, but curved around the foul pole and landing in the seats on the “foul” side (think of the Pesky Pole in Fenway Park) were called foul balls. To further muddy these waters, consider the following situation: say the score was tied 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, with a runner on third base. If the batter hit the ball out of the park, he was given credit for only a single, the reason being that the winning run had scored from third needing just a single, thereby ending the game.

These are just examples of how non-sabermetrical factors (in this case, changes in rules) have affected home runs. It would be a statistical nightmare to try to go back and “fix” these totals. Perhaps in the long run, things balance out, perhaps not. In any event, there’s not much that can be done. Babe Ruth will forever have 714 home runs. Not 713 or 715.

We now present ten random questions, realizing that many, many other questions could follow:

• Can one compare the fielding of Johnny Evers with that of Bill Mazeroski?

• Were the baseballs of 1901, 1920, 1930, 1968 and 2001 the same?

• Would Ty Cobb spike Jackie Robinson?

• Was Mark McGwire a better home run hitter than Mickey Mantle?

• What would the 1932 statistics of Jimmie Foxx have earned him in 2005?

• If the Designated Hitter rule was in effect in 1914, would Babe Ruth have remained a pitcher?

• What if Willie Mays had been a free agent in 1960?

• What numbers would have been recorded by Josh Gibson if he played for twenty seasons in the major leagues?

• Who threw the speediest fastball: Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Bob Feller or Nolan Ryan?

• Have Major League Baseball records been compromised of late?

Let’s do some rambling. Both Evers and Mazeroski are in the Hall of Fame. Were the fields of 100 years ago as well kept as Forbes Field in 1960? What if Evers used Maz’s glove and vice versa? Would the cleaner baseball of the 1960s be a help or hindrance for the infielder of a century ago? Would Maz have hit the Series-winning home run if Yankee hurler Ralph Terry had thrown a 1910 baseball?

You can surely think of several scenarios in which some of the factors listed above could have changed the game. Some of these factors are connected. For example, some batters now wear what amounts to body armor to protect their elbows from fastballs or ankles from foul balls. Helmets are lighter yet more protective. Equipment has evolved. One hundred years ago, players didn’t have helmets or elbow pads. Pitchers still pitched inside, and players were still hit by pitches, but without the body armor, players either played hurt or they were placed on a disabled list. Now, oftentimes a pitcher is warned if he pitches inside. That’s not a rule change, per se, but it is a non-sabermetrical factor that has affected the game.

When the duration of the regular season was lengthened from 154 to 162 games in 1961, Ford Frick was the Major League Baseball commissioner (he served as commissioner from 1951 to 1965, after having been the president of the National League from 1934 to 1951). He ruled that any records which surpassed those of the 154-game season but which also were made after 154 games (say, in the 161st game), would contain an asterisk. The most famous case was with Roger Maris and his chase of Babe Ruth’s 60-homers-in-a-season record. Another example was Maury Wills’ assault on the season stolen-base record of Ty Cobb (96). Wills heisted 104 bases in 1962. Frick would not budge on his decision to have two records, one with an asterisk. Eventually, the asterisk was struck from the record book; the point is now moot as several players have eclipsed the totals of Ruth and Maris, and of Cobb and Wills. However, as mentioned above, the asterisk gave players, fans, and sportwriters food for thought for decades.

A Hot-Stove League QuestionList some other “non-sabermetrical” factors and specific questions.

A Fantasy League QuestionYou have just been named president of the National League for a day. Under the current agreement, when an interleague game is played in the National League city, the Designated Hitter is not used. Only players who field a position (including the pitcher) may bat. Conversely, in the American League city, the Designated Hitter is used and bats for the pitcher. One of the teams in the National League has a pitcher with a 10-game hitting streak. We’re not sure what the record is (

The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book

does not contain this entry), but let’s say it is ten games and you have a dilemma. If the pitcher pitches, does he take part in the game? If the Designated Hitter bats for him and goes 0 for 4, does the pitcher then lose his hitting streak? Do you advise the National League manager to bat the pitcher? Here are the offical rules from Major League Baseball:

The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book

does not contain this entry), but let’s say it is ten games and you have a dilemma. If the pitcher pitches, does he take part in the game? If the Designated Hitter bats for him and goes 0 for 4, does the pitcher then lose his hitting streak? Do you advise the National League manager to bat the pitcher? Here are the offical rules from Major League Baseball:

Consecutive Hitting Streaks

: A consecutive hitting streak shall not be terminated if the plate appearance results in a base on balls, hit batsman, defensive interference or a sacrifice bunt. A sacrifice fly shall terminate the streak.

: A consecutive hitting streak shall not be terminated if the plate appearance results in a base on balls, hit batsman, defensive interference or a sacrifice bunt. A sacrifice fly shall terminate the streak.

Consecutive-Game Hitting Streaks

: A consecutive-game hitting streak shall not be terminated if all the player’s plate appearances (one or more) results in a base on balls, hit batsman, defensive interference or a sacrifice bunt. The streak shall terminate if the player has a sacrifice fly and no hit. The player’s individual consecutive-game hitting streak shall be determined by the consecutive games in which the player appears and is not determined by his club’s games.

: A consecutive-game hitting streak shall not be terminated if all the player’s plate appearances (one or more) results in a base on balls, hit batsman, defensive interference or a sacrifice bunt. The streak shall terminate if the player has a sacrifice fly and no hit. The player’s individual consecutive-game hitting streak shall be determined by the consecutive games in which the player appears and is not determined by his club’s games.

Do any other non-sabermetrical factors come into play?

Inning 8: Park Effects

Regarding the effects of specific playing fields, James again uses his axiomatic structure to describe outside influences on statistics. One of his “known principles of Sabermetrics” states, “Batting and pitching statistics never represent pure accomplishments, but are heavily colored by all kinds of illusions and extraneous effects. One of the most important of these is park effects.” Anyone who has examined the numbers attained by players at Coors Field in recent years would certainly attest to that. But just how does one determine if a park favors hitters or pitchers?

Continuing the use of runs as the “currency,” we can determine if a ballpark is more conducive to scoring runs or preventing them. A study of park factors provides an interesting look into how offensive statistics have changed over time as well. But what aspects of a ballpark contribute to its being designated “hitter friendly” or “pitcher friendly?”

The most obvious one is the distance of the fences from home plate, as that can seriously impact the number of home runs hit, or not hit. The last incarnation of the Polo Grounds in New York City, the home park of the Giants from 1912 to 1957, and for some time the Yankees as well, is considered a “pitchers’ park.” According to Phillip Lowry’s wonderful publication

Green Cathedrals

, the distance from home plate to the left field wall was never more than 287 feet, and down the right field line was never more than 258. It seems that the Polo Grounds was a “hitters’ park” as far as home runs were concerned, but a “pitchers’ park” for other factors. The clubhouse steps in center field were 460 feet from the plate, thus giving the stadium a very distinctive horseshoe shape.

Green Cathedrals

, the distance from home plate to the left field wall was never more than 287 feet, and down the right field line was never more than 258. It seems that the Polo Grounds was a “hitters’ park” as far as home runs were concerned, but a “pitchers’ park” for other factors. The clubhouse steps in center field were 460 feet from the plate, thus giving the stadium a very distinctive horseshoe shape.

Other books

Lock In by John Scalzi

How to Save a Life by Amber Nation

The Wilde Side by Janelle Denison

The Hunted by Heather McAlendin

Beyond This Time: A Time-Travel Suspense Novel by Charlotte Banchi, Agb Photographics

The Proposal by Katie Ashley

Confessions of the World's Oldest Shotgun Bride by Gail Hart

Confessions of a Window Cleaner by Timothy Lea

Regression by Kathy Bell

Inseverable: A Carolina Beach Novel by Cecy Robson