The Sahara (8 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

If Cambyses thought that cannibalism among the troops was the worst of his problems, he had yet to learn the fate of the force he sent into Egypt’s western desert.

While en route to Kush, Cambyses sent 50,000 of his soldiers west into the desert to march against the oasis of the Ammonians, or Siwa, which Herodotus says was known in Greek as “the Island of the Blessed”. On what was reckoned to be a seven-day journey across the desert, Cambyses’ army got as far as “the town of Oasis”, which may be Kharga (although Bahariya is another likely candidate). After they set out from Oasis, Herodotus writes, “thenceforth nothing is to be heard of them, except what the Ammonians... report. It is certain they neither reached the Ammonians, nor even came back to Egypt. Further than this, the Ammonians relate as follows: That the Persians set forth from Oasis across the sand, and had reached about half way between that place and themselves when, as they were at their midday meal, a wind arose from the South, strong and deadly, bringing with it vast columns of whirling sand, which entirely covered up the troops and caused them wholly to disappear. Thus, according to the Ammonians, did it fare with this army.”

The failure of these military campaigns was an embarrassing failure for the new Pharaoh, especially after the early promise of his swift initial conquests. The country was never fully subdued and after just three years Cambyses was forced to head back to Persia, to deal with a pretender to his throne. He never got there, being accidentally killed in 522 BCE on the homeward journey. In spite of their best efforts, Cambyses’ successors never entirely quelled the periodic uprisings that occurred, including those launched by the desert tribes.

Persian rule came to an end with the arrival of Alexander of Macedon in 333 BCE. Alexander’s conquest of Egypt was carried out with the same relative ease as Cambyses’ two hundred years earlier. The local population saw Alexander as a liberator, particularly welcome because he was happy to leave most aspects of domestic, non-military administration in the hands of the Egyptians. Alexander also demonstrated a high regard for Egyptian religious and cultural traditions, which made a favourable impression on local priests and the population at large.

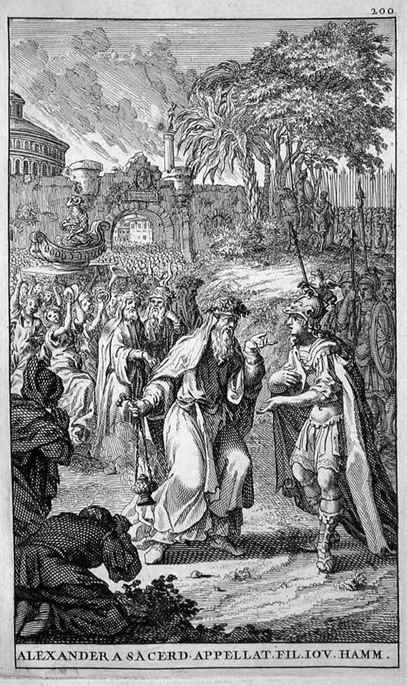

The year after arriving in Egypt, Alexander and a small band of followers marched eight days through the Sahara to Siwa, to consult with the Oracle of Ammon, one of the ancient world’s most venerated sources of prophecy and wisdom, which Cambyses’ army signally failed to destroy. First-hand reports of the expedition were made by two of Alexander’s friends, Callisthenes and Aristobulus of Cassandreia; the former was Alexander’s court historian, the latter an architect and military engineer. Unfortunately, these accounts have not survived but the historian Arrian, whose account of Alexander’s Saharan expedition is now the best available source, consulted them.

For Alexander, the journey to the Oracle was a shrewd political move that endeared him to his new subjects. It also fulfilled his own personal ambition to show himself the equal of Perseus and Hercules, who had similarly consulted the gods. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was the first person to encourage him to identify himself as the son of the Greek god Zeus. (Although it is common for mothers to think well of their children, persuading a boy that he is the son of a god must invite psychological disorders that would require lifetimes of therapy to unravel.)

Alexander the Great as the god Zeus-Ammon

In keeping with Alexander’s supposedly divine mission, the chroniclers were excited to report miracles that accompanied their journey to Ammon. Travelling along the Mediterranean coast to Paraetonium, today the seaside resort of Marsa Matruh, Alexander’s party turned south into the desert. Arrian writes that although this route is largely waterless, Alexander’s small band enjoyed plentiful rain as they went. While rain is not unknown here, Arrian also records other more remarkable details to demonstrate the divine nature of Alexander’s mission. Arrian tells us there were “two crows flying in advance of the army [that] acted as guides to Alexander.” Arrian further notes that Ptolemaeus son of Lagos claimed: “two serpents preceded the army uttering speech, and Alexander bade his leaders follow them and trust the divine guidance; and the serpents did actually serve them as guides for the route to the oracle and back again.”

Whatever talking beasts might or might not have accompanied Alexander, upon his arrival he was greeted by the priests of the Temple as the new, rightful Pharaoh of Egypt. Satisfied, Alexander henceforth insisted on being referred to by this new title, Zeus-Ammon. Coins from the period depict Alexander as Zeus, complete with ram’s horns signifying his divinity. After Alexander’s visit, the Oracle of Ammon enjoyed an even more elevated status across the ancient world, with a notable increase in supplicants travelling there in the hope of a consultation with the Oracle.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, Ptolemy, a life-long friend and trusted general, seized power in Egypt, taking the title of Pharaoh and establishing the Ptolemaic Dynasty that was to last for the next three hundred years. Ptolemy, whose name is the Greek for “aggressive” or “warlike”, crowned himself Ptolemy I Soter, or Ptolemy the Saviour. His male heirs all took the same name, while females in the dynastic line were named either Cleopatra, “father’s glory”, or Berenice, “bearer of victory”.

Not content to control the desert lands they inherited, the Ptolemies were soon extending their control west into Libya and south into the Sudan. While any Egyptian Empire was tied to the Nile, Ptolemy recognized that the oases, too, were of great importance. Strung out through the desert along the trans-Saharan trade routes, not only were they a source of taxation, but they were also useful bases from which to launch raids. As a result, a sizeable garrison was stationed at the oasis of Bahariya and a temple dedicated to Alexander the Great, which was only uncovered in the 1930s, was built.

The elevated status of the Saharan Oracle did not survive the Ptolemies. Almost exactly three hundred years after Alexander’s visit to Siwa, Strabo wrote the following about Oracles in Book XVII of his

Geography

: “In ancient times [they were] held in greater esteem than at present. Now they are generally neglected for the Romans are satisfied with the oracles of Sibyl. .. Hence the oracle of Ammon, which was formerly held in great esteem, is now nearly deserted.” This decline in part resulted in a concurrent dropping off in attention paid to the inhabitants of the oases by their ostensible rulers in Memphis.

The Romans

The razing of Carthage in 146 BCE marked not only the end of the third Punic War but also the end of Carthaginian civilization itself As Polybius wrote in his

Histories

, “Scipio, when he looked upon the city as it was utterly perishing and in the last throes of its complete destruction, is said to have shed tears and wept openly for his enemies... realizing that all cities, nations, and authorities must, like men, meet their doom.”

At that time Rome was not interested in establishing colonies in North Africa. Nevertheless it ended up ruling the region, which it seems almost to have acquired by accident, for five centuries. For its first one hundred years in North Africa, Rome did little more than appoint a senator to the region and collect tribute, both done annually. Eventually, belying these humble beginnings, Rome’s North African provinces, including Egypt, would be the breadbasket of the empire and consequently the most important of all Roman possessions. Much changed from when Horace described Roman Africa as

Leonum arida nutrix

or dry nurse of lions.

First occupying the Tripolitanian ports that were the hubs of trans Saharan trade - Sabratha, Oea (Tripoli) and Leptis Magna - Rome took a share of the profits made from any goods that emerged from the desert. Later, after Julius Caesar landed in North Africa to destroy his rival in

Rome’s civil war, Pompey, and his Numidian allies, Rome pursued more permanent territorial gains. The old kingdoms of Numidia and Mauretania, eastern Morocco and the bulk of Algeria were annexed to become the re-titled Roman province of Africa Nova, thereby distinguishing it from Africa Vetus, or Old Africa, which covered north-eastern Algeria and northern Tunisia.

The process of Romanization itself did not begin in earnest until Octavian-who in 27 BCE was styled Augustus, Rome’s first emperor became the undisputed master of Roman Africa in 36 BCE, eight years after the murder of his great-uncle and adoptive father, Julius Caesar. In 30 BCE Octavian also began to rule Egypt, after the defeat and suicide of his fellow triumvir, Antony and Antony’s paramour Cleopatra. The event is recorded with understatement in the

Res Gestae Divi Augusti

(the Deeds of the God Augustus), where it is written: “I added Egypt to the empire of the Roman people.”

That relative peace prevailed is clear from the small number of Roman soldiers stationed along the desert’s borders. With various client rulers in place, as well as soldiers turned farmers, Rome was able to maintain order for much of this period with about 5000 troops. This is not to say that the Romans were not alive to potential threats from the Sahara proper. There are many

ostraka

or potsherds, shards of pottery that record the comings and goings of local tribes, including details such as the tribe’s name, the numbers moving, their direction, what livestock they were leading, and a note of any goods being transported.

The Romans also made a number of trips deep into the Sahara which do not appear to have been military but more aimed at exploration and developing friendly relations with desert allies. One of these, led by Septimius Flaccus at the end of the first century CE, took four months and the Romans are believed to have reached the Tibesti Mountains. Another expedition, under Julius Maternus, travelled to Agisymba, the place where rhinoceroses gather. While Agisymba has not been definitively identified, Ptolemy’s description of high mountains, the journey from the Fezzan and the preponderance of large animals suggests it was in the Lake Chad area.

Rome never tried to conquer the desert tribes, nor were attempts made to garrison the oases of the desert interior. In spite of this, Rome’s presence was felt throughout the desert, from Egypt and the Sudan to West Africa and south of the Atlas Mountains. Trade links between Rome and inhabitants of the desert remained numerous and diverse. One major indication of just how widespread they were was the circulation of Roman coins throughout Saharan Africa, which could still be found in the towns of the north-central Sahara as recently as 1900. It is also believed that the most commonly used word for money in much of North Africa, filoos, derives from the Latin word follis, a common, low denomination bronze Roman coin.

The Garamantes

Although settling in their central-Libyan homeland around 1500 BCE, it is only with Herodotus that our written record of the Garamantes begins, when he writes: “Further inland toward the South, in the part of Libya where wild beasts are found, live the Garamantes, who avoid all intercourse with men, possess no weapons of war, and do not know how to defend themselves.” Like the Phoenicians, we do not know what the Garamantes called themselves, so we must rely on their Greek name, which the Romans, and subsequently everyone else, adopted.

We are, however, better able to piece together an understanding of the Garamantes than any number of their neighbours during this time. One of the glories of the Sahara is its rock art, and this provides us with substantial detail about Garamantean culture, and an idea of how far it spread in the central Sahara. Recent archaeological digs have also increased our knowledge, and surprised everyone with how much more substantial and numerous Garamantean towns were than previously thought.

Unlike other Saharan cultures, the Garamantes only moved into the Fezzan, from the Mediterranean basin, after the process of desertification had taken hold. Once there, they developed an innovative hydrological system that allowed them to farm in the Sahara for centuries. As a result, the Garamantes ruled over virtually the entire Fezzan region from their capital, Garama, for close to a thousand years from 600 BCE.

The Garamantes owed their success entirely to tapping the vast aquifers that lie below the limestone desert floor. By digging an elaborate series of tunnels - or rather making their slaves dig these - they could unleash huge quantities of otherwise hidden water. The fifth-century writer and sometime alchemist Olympiodorus of Thebes wrote of the Garamantes’ tunnels, foggaras in Berber, that they went down as far as 120 feet before releasing free-flowing jets of water. By taking advantage of slave labour and controlling trans-Saharan trade routes, it is thought that the kingdom eventually covered 70,000 square miles.