The Sahara (27 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

According to the tradition cited by Graves, the Libyan Desert was also home to another fearful creature, the Gorgon Medusa and her sisters, Stheno and Euryale. Indeed, the Hellenes tended to view the whole of ancient Libya, that is the Sahara, as a world of demons and evil, lying as it did beyond the civilizing effect of mainland Greece. The goddess Libya herself, representing the whole of alien North Africa, was said to be a daughter of King Epaphus of Egypt, a son of Zeus, who appeared to Jason of the Argo fame, dressed in goatskins.

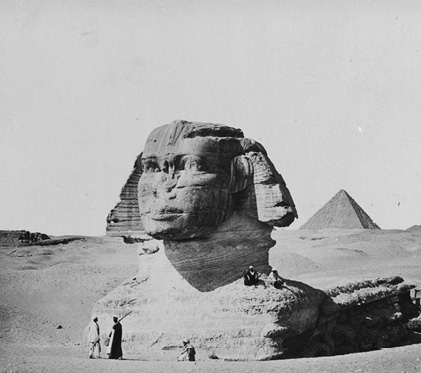

Riddle of the Sphinx

The most famous mythical Egyptian creature adopted and recast by the Greeks is the Sphinx. It is worth mentioning that the Greeks subverted the Egyptian idea of therianthropes: whereas the Egyptians had animal heads on human bodies, the Greeks, with the exception of the minotaur, had human heads on animal bodies. This animal, whose name is from the Greek meaning “the strangler”, was for the Egyptians the result of the union of Gaia, the earth, and Pontus, a sea-god and son of Gaea, whom she produced herself In the Egyptian tradition the Sphinx represented the divine power of the (male) Pharaoh in the form of a human-headed lion, watching over Egypt in life and death. For the Greeks, the Sphinx was a winged female whose role was to torment the city of Thebes.

In this guise the Sphinx was famous for the riddle she posed to travellers who crossed her path. The most famous version runs: “What being, with only one voice, has sometimes two feet, sometimes three, sometimes four, and is at its weakest when it has the most?” Giving an incorrect answer to the riddle resulted in the Sphinx throttling and eating the unfortunate victim. The story goes that the Sphinx’s reign of terror ended when Oedipus arrived at Thebes and guessed the correct answer. In Graves’ version of Oedipus’ encounter with the Sphinx, he replies, ‘“Man... because he crawls on all fours as an infant, stands firmly on his two feet in youth, and leans on a staff in his old age.’ The mortified Sphinx... dashed herself to pieces in the valley below.”

From the neoclassical period in Europe, Sphinx statues became commonplace at the entrance of buildings, freemasons in particular adopting the creature as symbolic of a wise, silent guardian. Like the Greeks and Romans, freemasonry used the antique to claim ancient legitimacy. In the late nineteenth century the Sphinx became a favourite subject of writers and artists looking to portray the darker side of myths of the sexually proscribed and echoing the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, the tree of knowledge and forbidden fruit.

The Sphinx was also a favourite subject of nineteenth-century artists, whose portrayals of the creature changed greatly between the century’s start and end, from the literal interpretation of the myth in Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’ 1808

Oedipus and the Sphinx

to Gustave Moreau’s sexually charged 1864 painting of the same name. By 1895, in Franz von Stuck’s

The Kiss of the Sphinx

it is hard to see anything but the supposed licentious nature or intent of the Sphinx, the original questioning of wayward travellers being transformed into a nightmarish, lust-filled vampiric embrace.

In the presumably less sexually charged atmosphere of the US Army Military Intelligence Corps, the Sphinx is that unit’s regimental insignia, and it was also the cap badge of the now disbanded Gloucestershire Regiment, which adopted the emblem after battling the French in Egypt in 1801. At one point, being attacked from front and rear, the Glorious Glosters were forced to fight back-to-back. They were consequently accorded the unique honour in the British Army of wearing a cap badge on the front and rear of their headgear. It is pleasing to see that, whether conceived in a pre-literate or post-Enlightenment era, the Sahara still manages to give birth to myths, ancient and modern.

Ask me no questions…

Poetic Muse

“Lesbia, you ask how many kisses of yours

would be enough and more to satisfy me.

As many as the grains of Libyan sand

that lie between hot Jupiter’s oracle,

at Ammon, in resin-producing Cyrene,

and old Battiades sacred tomb.”

Catullus (c. 84-c. 54 BCE)

The Sahara has been a source of inspiration for poets for as long as they have been exposed to it. What ancient European poets such as Catullus and Lucan knew about the desert was derived from myths and conquests. One of the more memorable of the classical verses based on historical events is by Lucan. In book nine of his

Pharsalia

, he recalls the Saharan meanderings of Cato the Younger and his band of followers during the course of the civil war in Rome when Cato was in opposition to Caesar:

Now near approaching to the burning zone,

To warmer, calmer skies they journeyed on.

…

As forward on the weary way they went,

Panting with drought, and all with labour spent,

Amidst the desert, desolate and dry,

One chanced a little trickling spring to spy.

In

Cato: A Tragedy

, written in 1712 by the poet, playwright, and politician Joseph Addison, Cato remembers his time in the Sahara, asking,

Have you forgotten Libya’s burning waste,

Its barren rocks, parch’d earth, and hills of sand,

Its tainted air, and all its broods of poison?

Making use of the famous Roman’s life-long struggle against tyranny, Addison’s play embraced the theme of opposition to monarchies and government oppression, in favour of republicanism and libertarianism. The play, with its Saharan imagery, proved inspirational to George Washington and other Founding Fathers. So enamoured was Washington of the play that in the midst of the War of Independence he had it performed to inspire the Continental Army, while they were camped at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777.

A similar vein of myth and conquest ran through the verses of later eighteenth- and nineteenth-century western poets, although these also turned for inspiration to the non-Saharan

Alf Layla wa Layla

, or

A Thousand and One Nights.

Largely set in Baghdad and other lands far from the Sahara, the

Arabian Nights

, as they also became known, quickly became the staple reference for anything considered Oriental, including the deserts of North Africa, by otherwise ignorant European poets and writers. First available to European readers in French, by 1713 at least four English editions had been published. In the absence of anything more scholarly, the

Arabian Nights

established itself as a primary source on the East in the western imagination. Peculiarly, it was concurrently read and understood both as a record of the people and places of the region and as a work of fantasy, complete with spirits and sorcery.

A large part of the Sahara’s poetic appeal for the non-native writer has been its image of pristine isolation. Depicting it as undisturbed and removed from the pollution of civilization, poets have often imagined that they would find peace there, contemplation supposedly being easier in a wild emptiness than in a city. Lord Byron writes about this desire for solitude in Childe

Harold’s

Pilgrimage

, exclaiming,

Oh that the desert were my dwelling place,

With only one fair spirit for my minster.

That I might forget the human race,

And hating no one, love her only.

While the majority of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century poets inspired by the Sahara did not travel there, this did little to dampen their enthusiasm for drawing on typical wilderness tropes, as they understood these in the abstract. These mainly consisted of silence, danger and the almost complete absence of human interference. Given the appeal of deserts as solitary places, it is not surprising that the Romantic poets found the Sahara a particularly evocative subject. It is worth noting that the “big six”, those poets who have for nearly two hundred years been at the core of the Romantic Movement - Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats - all allude to the Sahara in their work. Defending his choice of foreign subject matter, Coleridge once said, “A sound promise of genius is the choice of subjects very remote from the private interests and circumstances of the writer himself”

One advantage of the unseen Sahara was that it provided these poets with an imaginative landscape radically different from more domestic settings such as London or the Lake District. Choosing to write about the desert they were also freer to experiment with different poetic forms, working in the alternative metaphorical space provided by the imagined. Shelley’s “Ozymandias” remains as popular now as when it was published in 1818; its opening lines are some of the most easily recognized in English verse:

I met a traveller from an antique land

‘Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert.

“Ozymandias” was written in friendly competition with Shelley’s fellow poet Horace Smith, both men having to produce a verse with the same title. Smith’s version opens with the lines:

In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows.

Shelley’s version became so popular that Smith renamed his own poem, hoping it might flourish if not in the shadow of Shelley. Unfortunately for Smith, his choice lost something of the power of its original single word title. “On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below” does not exactly trip lightly off the tongue.

A similar composition competition took place in 1818. Taking part in it, Keats wrote to his brothers, “The Wednesday before last [February 4] Shelley, Hunt, and I, wrote each a sonnet on the river Nile.” Apart from the common theme, the self-imposed challenge also stipulated that the verses had to be composed in fifteen minutes or less. The results were as impressive as one would expect from such poetic heavyweights. Leigh Hunt produced “A Thought of the Nile”, and Shelley and Keats both entitled their poems “To the Nile”. Keats included the following evocative reference to the desert beyond the Nile:

We call thee fruitful, and that very while

A desert fills our seeing’s inward span:

Nurse of swart nations since the world began,

Art thou so fruitful?

…

‘Tis ignorance that makes a barren waste

Of all beyond itself. Thou dost bedew

Green rushes like our rivers, and dost taste

The pleasant sunrise.

It was not just English poets who sought to evoke the Sahara. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published

West-ostlicher Diwan

, or

West-East Divan

, in 1819 and an updated version in 1827. Diwan is a twelve-book collection of lyrical poetry and Goethe’s last major poetic cycle. A lifelong admirer of Middle Eastern cultures, Goethe saw in the East the pre-classical roots of western civilization, including the origins of language and poetry, and his magnum opus as both an exchange of cultural ideas between Occident and Orient and a philosophical or spiritual journey. In

Hegira

, and the 195 poems that follow it, Goethe’s intention was to