The Sahara (12 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

Saharan resistance among the Berbers was substantial, if poorly organized and disunited. Furthermore, many Berber leaders recognized that the future did not lie in resisting this overwhelming force. Chiefs who made peace with the Arabs were usually allowed to keep their realms, if they converted to Islam and paid tribute to their Arab conquerors. The sincerity of conversions made under duress was questionable. Ibn Khaldun wrote that the Berbers were guilty of apostasy twelve times before they converted sincerely. After the Ummayad caliphate was established in the second half of the seventh century, the goal to dominate the Sahara and its troublesome tribes was more clearly defined, with religious and military conquest marching together.

The most serious challenge to Arab regional supremacy at this time was the uprising started in the 680s, by the legendary tribal leader, al-Kahina, the seer. Variously claimed as a Jewess and a Christian and described as a witch or a sorceress, al-Kahina can be likened to a Berber Boudica who, through her bravery and a desire to see her tribe remain free of foreign domination, inspired others in a series of ultimately doomed revolts. Described as a beauty with the gift of prophecy, she put this last skill to good use, sending her sons to her Arab enemies to be raised to become successful commanders of Arab armies, hence attaching some glory to the Berbers from a story that is otherwise characterized by defeat and subjugation.

Al-Kahina herself died fighting the Arabs in around 702, her death in effect marking the end of Berber resistance in the desert. Since then, al-Kahina has been adopted as an inspiration by an array of disparate groups, from the more obvious constituencies of Berber nationalists and Maghrebi feminists to less likely followings such as Arab nationalists and even French colonialists.

The arrival of Islam led to the almost total disappearance of Christianity from the Sahara, which retreated across the Mediterranean to Rome, not making another appearance until the nineteenth century when the European invaders reintroduced it, although without any real impact on the local population. Noting the decline of Christianity, Gibbon wrote plaintively that “The northern coast of Africa is the only land in which the light of the Gospel, after a long and perfect establishment, has been totally extinguished.” As for Islam at the time of the Arab invasion, it was still a century away from becoming established in writing, which meant the beliefs of military commanders were what carried the day.

The evolution of a scholarly class entrusted with establishing orthodoxy was only a matter of time, however. Some writers, among them the tenth-century Andalusian-Arab geographer and historian al-Bakri, claim that the more remote desert-dwellers long remained beyond the religious pale. In his

Book of Highways and Kingdoms of North Africa

, al-Bakri reports a tradition of the prophet Muhammad that on Judgment Day the people of the northern Sahara will be led to hell, “as a bride to her groom”. Elsewhere, al-Bakri writes that certain apostates had reverted to worshipping a ram god.

Travellers, Chroniclers, Geographers

‘‘A desolate, extensive, difficult country.”

The Sahara as described by al-Muqaddasi (946-c. 1000)

If one were to offer a single observation about the period following the seventh-century Arab invasion of North Africa, one could say it was a time of tumult and uncertainty, as indigenous peoples and newcomers both struggled to adjust to the altered reality of life. Once the Ummayad caliphate had ostensible control of the Sahara, the local Berber tribes more or less recognized the suzerainty of the caliph. This was demonstrated mainly by the payment of a nominal tribute to the office of the caliph. In reality, those living in the Sahara remained largely beyond the control of any distant, central authority - a situation which pre-dated by a long way the Arab invasion and continues into the modern era. Local emirs controlled their own tribes and maintained the formal right to command confederations of kinsmen and armed militiamen in neighbouring oases as far as their territorial remit permitted.

In 750 the Abbasids overthrew the Ummayad dynasty and founded Baghdad as their new capital. The Abbasid ascendancy and attendant founding of Baghdad ushered in the so-called Golden Age of Islam, an unparalleled time of invention and learning which properly lasted until the thirteenth century. Abbasid control of the Sahara was never as great as that of their Ummayad predecessors and our knowledge of events in the Sahara during this period relies on the work of a disparate group of Islamic travellers, chroniclers and geographers. The political history of the Sahara during this period was dynamic. Rising dynasties took control only to be forced to seek client states to support them, this authority in turn being challenged by another young pretender. For example, the Aghlabids, who were once a client state of the Abbasids, and the Fatimids, who overthrew both Aghlabids and Abbasids, concurrently controlled the Maghreb and Ifriqiya, while to the Sahara’s north, al-Andalus was taken over by a surviving member of the Ummayad dynasty.

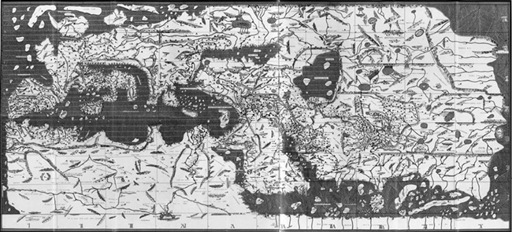

One important source on the Sahara to have survived from the tenth century is Mohammed Abul-Kassem Ibn Hawqal. A native of southern Turkey, Hawqal spent nearly three decades travelling in the Islamic world and beyond before publishing his most famous work,

Surat al-Ardh

(Picture of the Earth) in 977, with an accompanying map of the world that has also survived. Hawqal’s cartographical efforts are notable as much for what is missing as what is there. Even though Hawqal himself writes that one of his contemporaries dismissed his map of Egypt as “wholly bad” and that of al-Maghreb as “for the most part inaccurate”, they remained an important source of information for later scholars because, although they take no notice of lines of latitude, they accurately record in days the distances between towns and cities.

Writing at the same time as Hawqal was the Jerusalem native, al-Muqaddasi (946-c. 1000) whose geography of the Islamic world,

The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions

, offers a description of the Sahara as

a desolate, extensive, difficult country. The population is constituted of many races. In their mountains one finds those fruits that occur generally in the mountains of the realm of Islam, but most of the people there do not eat them... In trade among them, gold and silver are not used; however, the Garamantes use salt as a means of exchange.

This last observation remains true to this day for the Garamantes’ successors.

In the mid-eleventh century the Fatimid caliphate in Cairo was playing unwilling host to the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, Bedouin confederations from Arabia. In order to be rid of their unwelcome guests, the Fatimids encouraged them to move west. It was an invitation they willingly accepted. This second Arab invasion had the greatest long-term impact on the cultural identity of the Sahara. Unwilling to adapt to local customs, the Hilalian invaders ensured that wholesale Arabization took place, including a permanent linguistic shift to Arabic. These neo-colonialists were also responsible for replacing the existing, carefully moderated system of agricultural land management familiar to the local nomads which best suited the local situation, destroying irrigation systems and felling trees on an unparalleled scale.

In the

Muqaddimah

, Ibn Khaldun writes: “Places that succumb to the Arabs are quickly ruined [because] the Arabs are a nation fully accustomed to savagery and the things that cause it.” In citing examples of the destruction wrought by the rampant Arab forces he says: “When the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym pushed through to Ifriqiya and the Maghreb in the eleventh century and struggled there for 350 years, they attached themselves to the country, and the flat territory in the Maghreb was completely ruined. Formerly, the whole region between the Sudan and the Mediterranean had been settled. This fact is attested by the relics of civilization there, such as monuments, architectural sculpture, and the visible remains of villages and hamlets.” The destruction was so absolute that Khaldun likened it to the arrival of “a plague of locusts”. Within just a few years, it is estimated that some 200,000 of these Bedouin herdsmen had descended on the region.

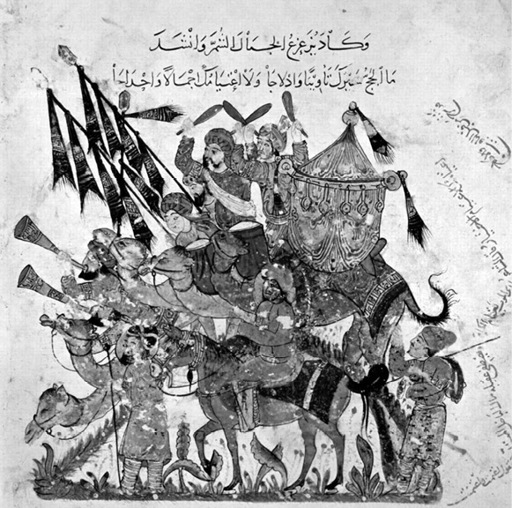

Although the practical destruction wrought by the Hilalian invasion was wholly negative, it opened up the region to outside influences that would prove crucial in future Saharan development. The invasion also spawned an oral epic that remains a classic of Arabic poetry. The

Taghribat Bani Hilal

is a fictionalized account of the Hilalian invasion that recounts the journey of the Banu Hilal from Cairo to Tunisia, in search of new pastures. The tale, like all oral traditions, evolved over time, growing in each retelling and watered both by the imagination of those reciting the tale and the urgings of audiences. Still recited by storytellers in Cairo and Algiers today, the poem was declared in 2003 by Unesco to be a “Masterpiece of Mankind” and now features in the organization’s Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity scheme. So while contemporary writers spoke of the Hilalian invasion as being like the end of the world, 1,000 years later the story of that invasion is reckoned to be a creative work of global consequence.

While the Hilalian invasion was in progress, in Andalusia Abu Ubayd Muhammad al-Bakri (1014-94) was writing the first comprehensive geography of the Sudanic belt, which was in part based upon interviews he conducted with merchants who had been there. Although he personally never travelled to any of the places that he wrote about, al-Bakri’s skill as a copyist and editor means that his

Book of Highways and of Kingdoms of North Africa

, first mentioned in 1068, is still important as a source of information regarding the Sahara, even if a number of his claims and descriptions have been called into doubt.

Al-Bakri acknowledged that an important motivation behind his book was to spread the message of Islam. Sadly, this resulted in his not infrequent belittling of non-Muslims, including a two-dimensional portrayal of blacks, in contrast to the frequent aggrandisement of his Muslim heroes. For example, when al-Bakri describes “The city of Ghana [which] consists of two towns,” he shows perhaps understandable favour towards the one “inhabited by Muslims... large and possessing 12 mosques in one of which they assemble for the Friday prayer. There are salaried imams and muezzins, as well as jurists and scholars.” In contrast, he dismisses the non-Muslim part of the town as “where the sorcerers of these people, men in charge of the religious cult live.”

Like al-Bakri, Muhammad al-Idrisi did not spend his time living in the Sahara but still felt able to write a geography of the region. His descriptions remain important, and are more accurate than those of al-Bakri. Born in Ceuta in 1100, al-Idrisi was a cartographer and geographer who spent the majority of his working life under the patronage of the Norman King Roger II of Sicily, who had recruited him after hearing about the North African’s reputation as a man of learning. The relationship between the Christian king and the aristocratic Muslim scholar was apparently a close one. In the preface to his most famous work, al-Idrisi says of his patron: “Of all the beings formed by this divine will, the eye may not discern nor the spirit imagine one more accomplished than Roger, King of Sicily, [who] has carried arms victoriously from the rising to the setting sun.” While accepting the expediency of flattering a patron, few modern readers would argue that al-Idirisi’s endorsement of Roger is inflated.

The world, from Ptolemy to al-Idrisi