The Sahara (7 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

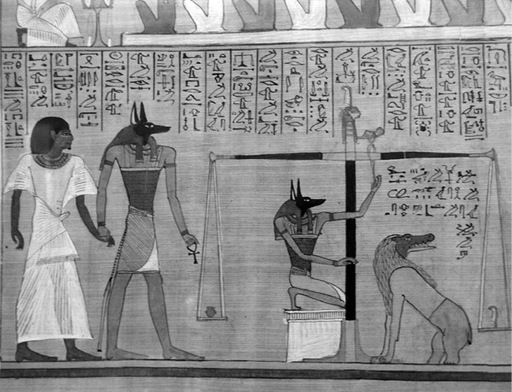

Egyptian funerary text, in the Land of the Dead

Thus, in the religion of Ancient Egypt, the Sahara was identified as the Land of the Dead, the nightly setting of the sun a profound

memento mori

. The closeness of this relationship between death and the desert is alluded to in the

Pyramid Texts

, a series of spells from the fifth and sixth dynasties that were found carved into the walls and sarcophagi of the pyramids at Sakkara. Reserved for the sole use of the Pharaohs, the

Texts

were intended to ease the progress of the dead into the afterlife and to make that journey a comfortable one. This was also the main function of the incantations that made up the Egyptian

Book of the Dead

, composed after and heavily influenced by the

Pyramid Texts

. The earliest of these culturally and historically invaluable documents date back to 2400 BCE, making them the world’s oldest extant religious texts which offer unparalleled insights into the early years of the Egyptian Empire.

The

Book of the Dead

and the

Pyramid Texts

illustrate the ancient kingdom’s religious observances and social mores which were refined and reinvented by later generations. For example, simple desert interment was the common pre-dynastic practice that lasted for centuries before formal mummification and elaborate tombs, as can be seen in Spell 662 of the

Pyramid Texts

where the dead king is told to “arise... Cast off your bonds, throw off the sand which is on your face.” In the

Book of the Dead

the deceased may converse with the gods, not always to praise them, and the gods are able to respond in kind. The disgruntled soul who finds himself in the Sahara bemoans his fate in Spell 175. Addressing Atum, the prime creator in the ancient Egyptian panoply of gods, the dead man’s soul cries out: “0 Atum, why is it that I travel to a desert which has no water and no air, and which is deep, dark and unsearchable?” Atum offers the not overly sympathetic response: “Live in it in content!” to which the corpse’s soul impatiently responds: “But there is no lovemaking there!”

The desert to the west of the Nile was also said to be the dwelling place of those gods associated with death, thereby ensuring the closest possible proximity between human burial and divine afterlife. In Spell 175, Atum refers explicitly to the one god who has particular power in the Sahara: “How good is what I have done for Osiris, even more than for all the gods! I have given him the desert.” Osiris, who is also known by the honorific Lord of the Western Desert and addressed using the formula “Hail to you who are in the sacred desert of the West!”, is of crucial importance not just for his later role as the god of the dead but also because he is, in spite of his divinity, the first character to die in ancient Egyptian religious mythology, having been murdered by his brother Set, or Seth, and resurrected by Isis. For his actions, Set was banished to spend eternity in the Sahara. The patron god of Lower Egypt, Set was also linked to desert winds and storms, becoming the embodiment of evil for the Egyptians.

After the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, Set continued to be seen as the god of storms but more generally became linked to chaos in any of its forms, including darkness, wars and the desert. For a short period in the nineteenth Dynasty, which spanned the twelfth and thirteenth centuries BCE, Set was revered once again as a great and powerful god who was actually responsible for holding back the desert from the agricultural land of the Delta and Nile Valley. It seems though, by the twentieth Dynasty, circa 1187 to 1064 BCE, Set had once more been demoted to his more damning role as a force for evil.

In the earliest days of the united Egypt, when the new empire was beginning to expand, the first direction it headed was west, both into the Sahara and along the coast from the delta. While the empire builders were trying to expand their realm to the west, it seems that the tribes in the Sahara were keen to push to the east. Whether aiming for temporary resettlement in the Nile Valley or a more permanent migration away from the desert, clashes between the Egyptians and the Saharan-based tribes were inevitable. In common with virtually all civilizations throughout history, ancient Egypt divided the peoples of the world into two main camps: themselves and everybody else. Accordingly, Egypt referred to everyone who lived in the Sahara more or less parallel to Upper Egypt as

Temehu

, while anyone who inhabited the lands west of the Nile and delta that abutted Lower Egypt were designated

Tehenu

. Both Berber tribes, or more likely associations or alliances of tribes rather than discrete blocks of people, were unlucky to come up against a swelling Egyptian empire, which would eventually control all of the oases of the Western Desert and the Sahara’s northern shores west of the delta.

The first therianthropic - or part-man, part-beast - god to be admitted to the Egyptian pantheon was Ash. Originally an indigenous Saharan god and a mirror image of the Egyptian Set, Ash is always depicted with a man’s body and animal’s head, usually that of one or other of the beasts found in the desert, including lions, vultures, hawks and snakes. Ash occasionally had more than one head at a time. Originally from the fecund oases, Ash was commonly associated with vines and viniculture, which also saw his fame spread to other regions where vines were grown, such as the Delta. Honouring the god, numerous seals from wine jars dating back to the Old Kingdom uncovered at Sakkara by the great Egyptologist Flinders Petrie were found with a common inscription: “I am refreshed by this Ash.” This simple sentiment, stated in the form of a prayer of thanks, is one with which wine drinkers up to the present day would no doubt concur.

The Phoenicians

Although famed as a sea-faring race, the Phoenicians also had an enormous impact on the Sahara because of the skills they brought with them. Although they did not physically colonize the Saharan interior, the knowledge they imported had a far more profound effect than any occupation. Their arrival also marked the introduction of iron into North Africa, which sparked an industrial revolution in the region.

When the Phoenicians first appeared on the North African coast, around 1200 BCE, Saharan populations had diminished considerably with the continuing desiccation of the land. The direct impact of iron working on the desert tribes was initially limited. For one thing, the Sahara now lacked the ready supply of wood essential for the process of smelting. Trans-Saharan communications were never absent from the desert, however, and as iron tools and weapons made their way south across the Sahara so too did knowledge of smelting, which was capitalized on by peoples living in wooded areas to the south of the desert, with evidence of early smelting operations established in Mauritania, Mali and Niger.

Although the Phoenicians were establishing themselves on the coast, building up their capital Carthage (Phoenician: Qart-hadasht or New City), they were not interested in controlling the tribes of the interior. Important as the Phoenicians and Greeks were to life along the Saharan littoral, the desert tribes kept themselves aloof (a state with which the Phoenicians were entirely satisfied). Many of the nomadic Imazighen, or Berbers, from the interior only involved themselves in the settlers’ lives when attacking and looting the colonies. As a result, the Saharans were seen as unruly, uncivilized and ungovernable, and they remained a source of danger to Phoenician and Greek settlers alike who had made their homes in the towns along the desert’s edge. The fractious Imazighen so badly harried the settlers that the Phoenicians were eventually forced to agree to pay the desert tribes tribute, or protection money, in order to guarantee a quiet life and allow themselves to secure their coastal holdings. Eventually Phoenician growth dictated a change in policy, and they began to extend their reach into the Sahara, building cities, forts and border ditches, which marked the reach of their influence.

The Phoenicians had long been transformed from seasonal traders to a settled presence with colonies all along the coast. No longer did they just come to North Africa on the back of favourable March winds, returning to their eastern Mediterranean homeland in September. Now they were permanent residents, and rulers, with customs that reflected the physical and emotional distance that separated them from Tyre. The fall of Tyre to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar in 573 BCE marked the end of the Phoenician Empire. From this point forth the Phoenicians of North Africa, with no eastern Mediterranean motherland, can properly be thought of as Carthaginians.

As Carthage grew and became more powerful it inevitably looked to pursue trade across the Sahara. By opening up previously unused paths across the desert, the Carthaginians could bypass their Greek rivals on the coast. Yet instead of being drawn from the sea and into the sand themselves, they relied on the locals to execute their trade missions for them. Using the existing Berber population to transport their goods for them, the Carthaginians opened up Saharan markets without having to endure the hardship and dangers that went with the terrain.

The Carthaginians also used Berber and Numidian mercenaries from the Sahara to swell the ranks of their army when necessary. As paid warriors, however, the desert fighters were as likely to take the side of their foes, especially if offered more money. As the Greek writer Polybius tells us, many erstwhile allies fought against Carthage when the Romans eventually vanquished it. Nor was this bloodletting restricted to the fall of Carthage in 146 BCE. Records show there were frequent revolts and uprisings on the part of the Berbers, Numidians, Libyans and others under the Carthaginian yoke. It seems that the most ruthless local officials were most favoured in the capital, but their inequitable rule led to much resistance and periodic violence against government authority.

Persian and Ptolemaic Dynasties

In 525 BCE, while the Carthaginians were extending their influence in the desert to the south, in the Sahara’s easternmost point the Persian King Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Persian Empire, was conquering Egypt. Having crossed the Sinai, Cambyses’ army clashed - or did not - with the Egyptians at the Battle of Pelusium, barely twenty miles south-east of the modern Port Said, the entrance to the Suez Canal. Whether or not any fighting actually occurred is a moot point. Herodotus writes that he visited the battlefield seventy-five years later, and that it was still strewn with the bleached skulls of fallen soldiers.

Even so, legend has it that the Battle of Pelusium was distinguished by the fact that no fighting took place. Instead, so the Macedonian Polyaenus notes in his

Stratagems in War

, the Egyptians ran away before an arrow was launched, being unwilling to harm the cats, dogs and ibises that they saw as sacred, and which Cambyses herded towards them. After this ignominious Egyptian defeat, Cambyses and his army marched on the Egyptian capital of Memphis without further opposition and Cambyses declared himself Pharaoh, launching 124 years of Persian rule in Egypt. From a Persian perspective, the ease with which Cambyses managed to conquer Egypt was an auspicious beginning to their North African sojourn.

Cambyses was keen to stamp his authority on the Egyptian Empire over which he now ruled and sought to do this with a number of military expeditions, including into the Sahara south and west of Memphis. Unfortunately for Cambyses, none of these military adventures produced the hoped-for results. Leading an army south to attack Kush in modern Sudan, “against the long-lived Ethiopians” as Herodotus describes them in his

Histories

, Cambyses was determined to secure Egypt’s southern border, and so set off to cross the desert in a straight line, instead of following the more circuitous course of the River Nile. Without adequate supply lines in place, his army was soon starving and in need of water.

As Herodotus tells us:

So long as the earth gave them anything, the soldiers sustained life by eating the grass and herbs; but when they came to the bare sand, a portion of them were guilty of a horrid deed: by tens they cast lots for a man, who was slain to be the food of the others. ‘X’hen Cambyses heard of these doings, alarmed at such cannibalism, he gave up his attack on Ethiopia, and retreating by the way he had come, reached Thebes, after he had lost vast numbers of his soldiers.