The Sahara (11 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

Over the course of St. Anthony’s long life - tradition has it that he died aged 105 - the temptations and torments to which the devil subjected him have provided plenty of inspiration for writers and artists. According to St. Athanasius, the devil visited St. Anthony “one night with a multitude of demons, he so cut him with stripes that he lay on the ground speechless from the excessive pain. For he affirmed that the torture had been so excessive that no blows inflicted by man could ever have caused him such torment,” adding that “the demons as if breaking the four walls of the dwelling seemed to enter through them, coming in the likeness of beasts and creeping things. And the place was on a sudden filled with the forms of lions, bears, leopards, bulls, serpents, asps, scorpions, and wolves, and each of them was moving according to his nature.”

Many artistic representations of the saint’s torments were to follow, the earliest extant examples of the genre being tenth-century frescoes from Italy. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries artists such as Martin Schongauer, Matthias Grunewald and Hieronymus Bosch focused on the more fantastical elements of the story, producing some genuinely terrifying work. The Torment of St. Anthony is the title of the earliest known painting of one of the greatest artists of all time, the personification of Renaissance man, Michelangelo. His Torment, painted when he was twelve or thirteen, follows Schongauer’s own engraving of the subject, to which the young Michelangelo has added his own landscape as a background, and altered Anthony’s expression from sorrow to saintly detachment.

Martin Schongauer’s engraving of St. Anthony’s torment

The Vandals

Nearly four hundred years after Rome took control of Mauretania, a Vandal army coming from Spain and led by King Geiseric did the same, beginning their own conquest of North Africa. The Vandals’ domination of North Africa, and far less successful encounter with the Saharan tribes, was not the longest stay of any foreign invader in the region, but whatever the Vandals lacked in longevity they made up for in drama. The most widely cited account of their journey from Europe to Africa is provided by the Roman historian Procopius who, in his

Wars of Justinian

, recounts that the Vandals crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in 429 at the invitation of the Roman general Boniface. Boniface soon regretted, and rescinded, the invitation; this did nothing to stop the arrival of the Vandals and their supporters. There followed a decade of fighting and conquest that left the Vandals in control of most of the Roman provinces.

Not all cities went willingly; Hippo was a famous example and underwent a lengthy siege in the third month of which St. Augustine died, aged 76. As related in

Sancti Augustini Vitta

, the Life of Augustine, by Possidius, who was present during the siege, Augustine’s last days were spent praying for the city’s inhabitants whose fate, being of the Roman faith, was not likely to be good at the hands of the Arian Vandals. Possidius records that Augustine “repeatedly ordered that the library of the church and all the books should be carefully preserved for future generations.” The siege lasted for fourteen months and when they eventually took the city the Vandals indulged in a destructive rampage that saw death and enslavement of the city’s inhabitants and its buildings burnt, except for Augustine’s church and library. Such was his reputation that the Vandals ensured his church and books were protected and preserved. In this instance at least, the Vandals failed to live up to their reputation for wanton destruction.

In a North African sojourn that lasted almost exactly one century, the Vandals successfully controlled their coastal subjects but not those living in the Sahara. Although Vandal settlements were largely confined to the coast and littoral, this did not keep them safe from the desert tribes. Whereas the Romans, as far as it was in their power, were unwilling to allow independence to the desert tribes, the Vandals did their best to adopt a policy of ignoring them, looking north instead to the Mediterranean. Even before the fall of Hippo, Geiseric had started building a fleet. As soon as it was ready, he launched himself with enthusiasm into a lucrative career of piracy, a calling he pursued until his death in 477.

The pursuit of plunder at sea meant that in the Sahara a number of independent kingdoms soon developed, remote from the heartland of Vandal territory. Those tribes that had retained their nomadic lifestyle also took advantage of the limited law and order exerted on the fringes of the Vandals’ empire, launching raids in increasing number through the fourth century. Saharan-based Berbers achieved at least two major victories against Vandal settlements between 496 and 530, and by the end of Vandal rule, the inhabitants of these areas may actually have welcomed the restoration of some strong, central authority.

When Byzantine forces landed in June 533 and attacked the Vandals, Geiseric’s decision to destroy all city walls, bar those of Carthage, came back to haunt his successors. Although his decision must have seemed a good idea to him at the time, it brought ruin to his heirs. The armies of Byzantium defeated the Vandals in just six months, and Procopius, apparently feeling the Vandals’ glory days were at an end made the withering observation that “of all the nations I know the most effeminate is that of the Vandals.”

The surrender of Gelimer at Mount Papua in western Numidia marked the end of the Kingdom of the Vandals and the transition of North Africa into a Roman province again. For the next century, the entire period of Byzantine rule in North Africa, oppression, revolts and insurrections were the touchstones of Berber- Byzantine relations, which only ended with the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in North Africa in 647, vanquished by the arrival of the Arab armies.

Anyone who thought life would be better under the Byzantines than under the Vandals was soon to be disappointed. Raids from out of the Sahara became more frequent than ever, and where Byzantine rule was stronger it was harsher too. For the mass of the population, rule from Byzantium was marked by greater interference in their lives, which included among other things swingeing taxation, to which the local tribes responded by revolting. The Romanized Berbers in particular, who under the Vandals had been treated no worse than anyone else, soon responded to Byzantine accession with open revolt.

Strong as they were, any influence the Vandals exerted over the Saharan tribes was limited. To a large degree this was the result of their self-imposed, if understandable, unwillingness to tackle the recalcitrant desert dwelling Mauri and Berber. Pursuing desert-based raiders - whose combative life has been formed around guerrilla tactics - deep into the Sahara is not something any sane city- or coast-based power would be keen to do. Once again, the desert proved to be a formidable barrier to full conquest by outsiders, and a safe haven for its own.

The Armies of Islam

In

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

, Edward Gibbon wrote of the Arab armies that swarmed into Africa in the seventh century: “The sands of Barca might be impervious to a Roman legion; but the Arabs were attended by their faithful camels; and the natives of the desert beheld without terror the familiar aspect of the soil and the climate.”

The ineluctable Arab invasion, after the introduction of the camel, had the most profound effect on the history of Saharan North Africa. The Arab conquest of the region was far more thorough than anything achieved by the Phoenicians, Romans, Vandals or any other previous invaders-Saharan life and culture were absolutely Arabized. From Roman through Vandal rule, most of the region’s denizens would have seen little change in their circumstances: not so under the Arab invaders. Bringing with them not only a new religion but also a language that was indivisible from that religion, the changes were radical, and had an immediate impact on every aspect of existence.

Arriving in Egypt in 639, in just seventy years the Arabs conquered all of North Africa, from the Nile to the Atlantic, with Romano Byzantine Africa becoming Arab Ifriqiya. As Gibbon says, “When the Arabs first issued from the desert, they must have been surprised at the ease and rapidity of their own success.” Their westward conquest followed the setting sun to al-Maghreb, (literally the West). Their ultimate African goal, Morocco, they called al-Maghreb al-Aqsa (the furthest West), and it was conquered in 682 by the Ummayad Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi, Gibbon’s “conqueror of Africa”. According to the Andalusian historian Ibn Idhari Al-Marrakushi, writing in his

Book of the Wondrous Story of the History of the Kings of Spain and Morocco

, on reaching the waters of the Atlantic at Rabat, Uqba rode his horse into the ocean, crying out, “Oh God, if the sea had not prevented me, I would have galloped on forever like Alexander the Great, upholding your faith and fighting the unbelievers!”

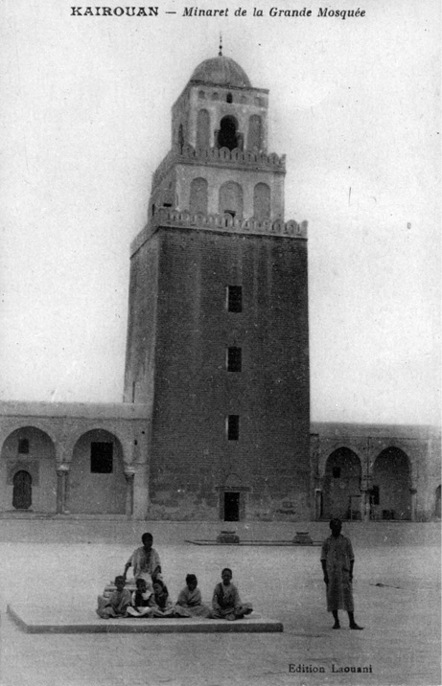

Uqba also founded the city of Kairouan, Tunisia. Rendered from the Arabic

qayrawan

, or caravan, the city was built on the site of an established campsite coming out of the desert. From here, one could travel north to Carthage and the coast, east to Egypt, west to the Atlas Mountains or south into the Sahara. As well as being the capital of Ifriqiya, Kairouan quickly developed into a centre of learning that was to exert a centuries-long influence on education and law throughout the entire Islamic world. Once Arabic was established as a written language, Islamic laws grew apace; in this, the religious authorities at Kairouan were instrumental.

The Muslim-Arab invaders who took control of the Sahara were distinct from earlier Roman and Byzantine conquerors, arriving as they did at the vanguard of a religiously inspired army. As “people of the book”, those Christians already in the Sahara were recognized by the Muslim conquerors as being superior to the pagan tribes, if still inferior to the Muslim faithful. As a result, Christians were initially accorded certain rights and protections not extended to non-Christianized Berbers and others, including freedom of worship.

Of the four main branches of orthodox Sunni Islamic law, two originated in North Africa: the Shaf’ite school from Cairo and the Malikite school from Kairouan. Both received large numbers of aspiring scholars from the Sahara who, once educated, returned home, graduates of Islamic law. These new graduates were highly admired in their oases and often achieved power among their kinsmen because of their learning. Thus, literacy led to religious authority, which in turn often resulted in political mastery too. The knowledge that the usually young scholars took home meant they could dictate what messages became religious orthodoxy in the Sahara. By the same token, the isolation of Saharan communities meant that any unorthodox interpretations of Islam could also be promulgated and flourish, guided by a heterodox scholar whose position was unassailable by any illiterate, secular authorities.

It should be said that the swift conquest of North Africa was not without local setbacks, retreats and military defeats. Arab armies conducted raids into the Sahara, although at this stage apparently without a sense that they were attempting the systematic conquest of the desert. They met with some stiff local resistance, with a few anti-Arab uprisings persisting for decades. These revolts led one Arab governor to declare despairingly, “The conquest of Ifriqiya is impossible; scarcely has one Berber tribe been exterminated than another takes its place.” The Roman term of opprobrium for any non-Roman – barbarian - had now evolved into an Arabic proper name, creating a Berber identity that saw them as a united people, rather than merely disparate desert tribes.