The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (48 page)

Read The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain Online

Authors: Betty Edwards

BOOK: The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain

12.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The portrait drawings throughout this book will demonstrate various ways of drawing different types of hair. There is obviously no one way of drawing hair just as there is no one way to draw eyes, noses, or mouths. As always, the answer to any drawing problem is to draw what you see.

If you have decided on a three-quarter view, please review the proportions for that view that I provided earlier in this chapter. Also, see Figure 10-35. One caution: Beginning students sometimes begin to widen the narrow side of the face and then, because that makes the face seem too wide, they narrow the near side of the face. Often, the drawing ends up a frontal view, even though the person was posing in three-quarter view. This is very frustrating for students, because they often can’t figure out what happened. The key is to accept you perceptions. Draw just what you see! Don’t second-guess your sightings.

Now that you have read all of the instructions, you are ready to begin. I hope you will find yourself quickly shifting into R-mode.

After you have finished:When the drawing is finished, observe in yourself that you sit back and regard the drawing in a different way from the way you regarded the drawing while working on it. Afterward, you regard the drawing more critically, more analytically, perhaps noting slight errors, slight discrepancies between your drawing and the model. This is the artist’s way. Shifting out of the working R-mode and back to L-mode, the artist assesses the next move, tests the drawing against the critical left brain’s standards, plans the required corrections, notes where areas must be reworked. Then, by taking up the brush or pencil and starting in again, the artist shifts back into the working R-mode. This on-off procedure con- tinues until the work is done—that is, until the artist decides that no further work is needed.

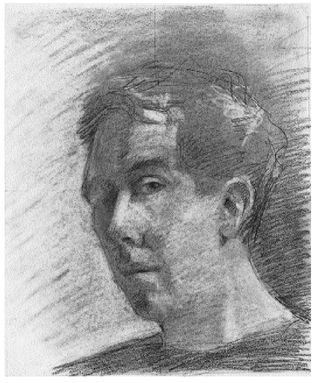

Fig. 10-37. The completed drawing: A self-portrait by instructor Brian Bomeisler.

“One of life’s most fulfilling moments occurs in that split second when the familiar is suddenly transformed into the dazzling aura of the profoundly new. . . . These breakthroughs are too infrequent, more uncommon than common; and we are mired most of the time in the mundane and the trivial. The shocker: what seems mundane and trivial is the very stuff that discovery is made of. The only difference is our perspective, our readiness to put the pieces together in an entirely new way and to see patterns where only shadows appeared just a moment before.”

—Edward B. Lindaman

Thinking in Future Tense,

1978

Thinking in Future Tense,

1978

This is a good time to retrieve your pre-instruction drawings and compare them with the drawing you have just completed. Please lay out the drawings for review.

I fully expect that you are looking at a transformation of your drawing skills. Often my students are amazed, even incredulous, that they could actually have done the pre-instruction drawings they now find in front of them. The errors in perception seem so obvious, so childish, that it even seems that someone else must have done the drawing. And in a way, I suppose, this is true. L-mode, in drawing, sees what is “out there” in its own way—linked conceptually and symbolically to ways of seeing and drawing developed during childhood. These drawings are generalized.

Your recent R-mode drawings, on the other hand, are more complex, more linked to actual perceptual information from “out there,” drawn from the present moment, not from memorized symbols of the past. These drawings are therefore more realistic. A friend might remark upon looking at your drawings that you had uncovered a hidden talent. In a way, I believe this is true, although I am convinced that this talent is not confined to a few, but instead is as widespread as, say, talent for reading.

Your recent drawings aren’t necessarily more expressive than your “Before-Instruction” drawings. Conceptual L-mode drawings can be powerfully expressive. Your “After-Instruction” drawings are expressive as well, but in a different way: They are more specific, more complicated, and more true to life. They are the result of newfound skills for seeing things differently, of drawing from a different point of view. The true and more subtle expression is in your unique line and your unique “take” on the model—in this instance yourself.

At some future time, you may wish to partly reintegrate simplified, conceptual forms into your drawings. But you will do so by design, not by mistake or inability to draw realistically. For now, I hope you are proud of your drawings as signs of victory in the struggle to learn basic perceptual skills and to control the processes of your brain.

Now that you have, with great care, seen and drawn your own face and the faces of other human beings, surely you understand what artists mean when they say that every human face is beautiful.

A showing of portraitsAs you look at the portraits on the following pages, try to mentally review how each drawing developed from start to finish. Go through the measurement process yourself. This will help to reinforce your skill and train your eye. Three of the drawings are instructional demonstration drawings from our five-day workshop.

A suggestion for a next drawingA drawing suggestion that has proven to be amusing and interesting is a self-portrait as a character from art history. A few such examples might include “Self-Portrait as the Mona Lisa”; “Self-Portrait as a Renaissance Youth”; “Self-Portrait as Venus Rising from the Sea.”

“The object, which is back of every true work of art, is the

attainment of a state of being,

a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. . . . We make our discoveries while in the state because then we are clear-sighted.”

attainment of a state of being,

a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. . . . We make our discoveries while in the state because then we are clear-sighted.”

—Robert Henri

The Art Spirit,

1923

The Art Spirit,

1923

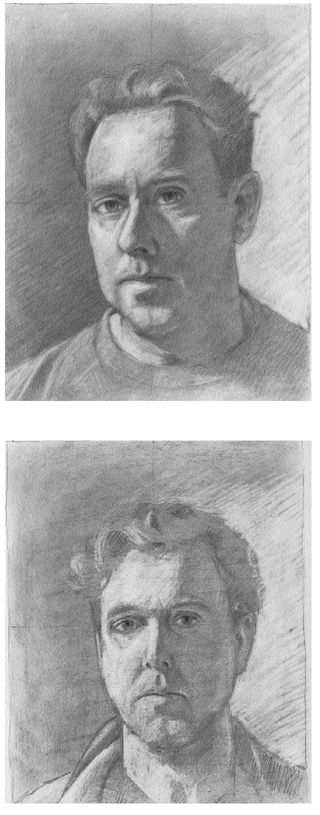

Two additional self-portraits by instructor Brian Bomeisler. Note how they differ one from another. You will find that your self-portraits will differ, reflecting the mood, feeling, and surroundings of each sitting. Remember, drawing is not photography.

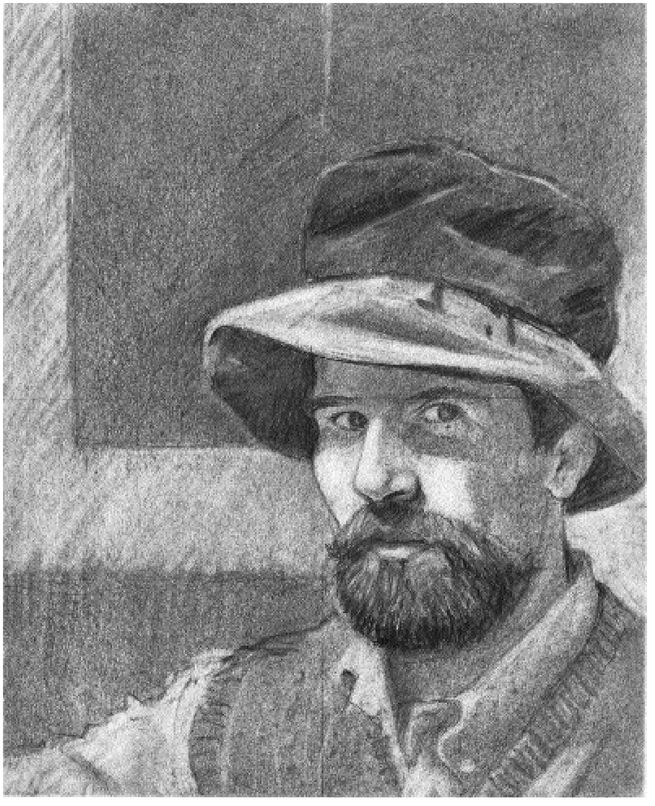

A beautiful self-portrait in light/shadow by instructor Grace Kennedy.

A three-quarter self-portrait by student Mauro Imamoto. The composition is especially fine.

11

Drawing on the Beauty of Color

“No one knows how far back in time the human passion for color evolved, but . . . its transmigration from one culture to another can be traced from archaeological fragments as old as recorded history.”

—Enid Verity

Color Observed,

1980

Color Observed,

1980

Miss Helen Keller, who was both blind and deaf, writes of color:

“I understand how scarlet can differ from crimson because I know that the smell of an orange is not the smell of a grapefruit . . . Without color or its equivalent, life to me would be dark, barren, a vast blackness. . . . Therefore, I habitually think of things as colored and resonant. Habit accounts for part. The soul sense accounts for another part. The brain with its five-sensed construction asserts its right and accounts for the rest. The unity of the world demands that color be kept in it whether I have cognizance of it or not. Rather than be shut out, I take part in it by discussing it, happy in the happiness of those near me who gaze at the lovely hues of the sunset or the rainbow.”

—Helen Keller

The World I Live In,

1908

The World I Live In,

1908

I

N AN AGE LIKE OURS, color is not the luxury it was in past centuries. We are inundated by manufactured color—surrounded, immersed, swimming in a sea of color. Because of sheer quantity, color is perhaps in danger of losing some of its magic. I believe that using color in drawing and painting helps us to recapture the beauty of color and to experience once again the almost hypnotic fascination it once had for us.

N AN AGE LIKE OURS, color is not the luxury it was in past centuries. We are inundated by manufactured color—surrounded, immersed, swimming in a sea of color. Because of sheer quantity, color is perhaps in danger of losing some of its magic. I believe that using color in drawing and painting helps us to recapture the beauty of color and to experience once again the almost hypnotic fascination it once had for us.

Human beings have made colored objects from earliest times, but never in such great quantity as now. In past centuries, colored objects were most often owned by only a few wealthy or powerful persons. For ordinary people, color was not available, except as found in the natural world and as seen in churches and cathedrals. Cottages and their furnishings were made of natural materials—mud, wood, and stone. Homespun cloth usually retained the neutral colors of the original fibers or, if dyed with vegetable dyes, was often quick to soften and fade. For most people, a bit of bright ribbon, a beaded hatband, or a brightly embroidered belt was a treasure to guard and cherish.

Contrast this with the fluorescent world we live in today. Everywhere we turn, we encounter human-made color: television and movies in color, buildings painted brilliant colors inside and out, flashing colored lights, highway billboards, magazines and books in full color, even newspapers with full-page color displays. Intensely colored fabrics that would have been valued like jewels and reserved for royalty in times past are now available to nearly everyone, wealthy or not. Thus, we have largely lost our former sense of the wondrous specialness of color. Nevertheless, as humans, we can’t seem to get enough color. No amount seems too much—at least not yet. True, quite a few individuals objected to the “colorization” of vintage black-and-white films. These arguments, however, were lost to commerce; most people preferred the colorized versions.

Other books

Prince of Dragons by Cathryn Cade

Target: BillionBear: BBW Bear Shifter Paranormal Romance by Chant, Zoe

The Book of the Bizarre: Freaky Facts and Strange Stories by Ventura, Varla

The Death Run (A Short Story) by Ruttan, Sandra

Man About Town: A Novel by Mark Merlis

The Modest and the Bold by Leelou Cervant

Time Traders II: The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time by Andre Norton

Changing Traditions, A Christmas Novella by Rachel Rittenhouse

Find Me in the Dark by Ashe, Karina

Cybernarc by Robert Cain