The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (24 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Remember, in 1866 Child had snuffed the

Freed Woman

only days after, in spite of, and regretting her sentimental approval in the

Independent.

Now, in its April 1868 issue, the

Prang’s Chromo

reprint of her admiration in “Illustrations of Human Progress” amplified the arrival of

Forever Free

with freakish timing. Written more than a year earlier, it could have only aggravated her sense of guilt.

About the same time, the

National Anti-Slavery Standard

published her “Plea for the Indian,” then reprinted it in pamphlet form. In it, Child reveled as Edmonia told how smartly she had defied stern authority:

Speaking of Edmonia reminds me of an impromptu witticism of hers. Some years ago, an old Calvinistic minister exhorted her to attend revival meetings, and frequently took occasion to reprove her love of frolic. Seeing her running and romping with some of the other girls before breakfast, he exclaimed, “Ah, you child of Satan!” “Good morning, father,” she exclaimed.

[345]

Child was helpless to erase the blessings she had sent to the printers. The two reminders could only have salted wounds from Edmonia’s repeated affront to her ban on carving marble without an order.

Years later, rechewing the record for the benefit of Sarah Shaw, she recalled her first reaction to

Forever Free,

“She wanted me to

write it up;”

then told a bold fib (or dwelled in deep denial): “I could not do it conscientiously, for it seemed to me a poor thing.”

[346]

The sharp proof of Edmonia’s perseverance remained on display in downtown Boston. Private comments and press notices

[347]

must have added to Child’s angst. The June issue of Susan B. Anthony’s

Revolution

magazine may have been the last straw.

Child honed her sharpest pen and wrote a “sincere letter” to Edmonia, blasting her poor judgment. Then she let friends like Harriet Sewall know how fiercely she had scolded. Her letter to Edmonia is lost, but she described writing it:

Somebody must check her thoughtless course. She literally takes no thought about money, and because she has been very generously aided, she draws upon friends of her race as if their sympathy was an inexhaustible bank entirely at her disposal. All this is very excusable in one so inexperienced and so entirely unacquainted with the customs of society. But for her own sake, it won’t do for her to go on so.”

[348]

Child bristled with sarcasm, adding, “if marble and freight are obtained by whistling ‘to raise the wind,’ she will probably send over a marble Pocahontas to be presented to the Chief of the Chippeways, the tribe to which her mother belonged.

Plainly tortured, Child soon wrote again in needy catharsis to say she would rather have given $50 than write her “sincere letter.”

[349]

She claimed a noble forgiveness as she anguished, “[Edmonia] has no calculation about money; what is received with facility is expended with facility. How could it be otherwise when her youth was spent with poor negroes and Indians?”

She went on to explain how Edmonia’s wild background somehow excused her offence yet provided ample reason to shut her down. “People who live in ‘a jumpety-scratch way’ (as a slave described his ‘poor white’ neighbors) cannot possibly acquire the habits of income and outgo. If she found all her bills for freight and marble paid, without expostulation from any quarter, she would soon send over another statue, in the same way.”

Edmonia’s situation also deteriorated in Rome, where she was sinking in debt. Bouyed by a bubble of praise from fans and wealthy buyers, she had entered the two Hiawatha groups and

Minnehaha’s Father

for sale at New York City’s crowded 1868 National Academy of Design show held in May.

[350]

Minnehaha

also appeared there, owned by an unnamed collector and not for sale. Creditors in Rome seeking the reassurance of a lien would find these assets beyond legal reach – but not before she borrowed again.

Her most important New England friends were slipping away. Adding to distance imposed by race, she now suffered, in their eyes, a lack of breeding and, not to be mentioned, fealty to the Pope.

Having boldly come out as a Roman Catholic, she again sought validation on the basis of her blood. Audacious in life and dauntless in her own civil war, she created a new life-size allegory,

Hagar

[351]

(Figure 26), her final return to “the freed woman,” which we discuss in the next chapter, and

Indians in Battle

(Figure 24), the last of her known marble Indian groups. It seems she borrowed money for marble again and again with no orders in hand.

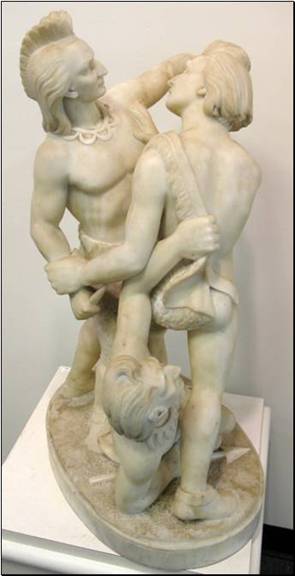

Figure 24.

Indians in Battle,

1868

Also called

Indian Combat

or

Indians Wrestling,

this group may be seen at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland OH. Photo courtesy Gabriel’s Auctioneers & Appraisers.

Edmonia created this ambitious group at a time when she was at odds with and probably furious at Mrs. Child. Standing thirty inches high, the marble is signed and dated 1868 but bears no title. Called “Indians wrestling” by a visitor to her studio that winter, the scene is not sport but war. The sharp tools appear far more deadly than the pen-knife once visualized by Mrs. Child.

Unlike the carved athletes of ancient Greece, the figures met Edmonia’s preference for modesty. The grim intensity of their faces seems to be an authentic portrayal of Indian custom. The composition also seems to escape neoclassical forms as it draws on the tangled violence and spiral form of earlier styles. Giambologna (Figure 25, below) and Fedi’s

Rape of Polyxena

(1865) were the talk of Florence before she headed for Rome.

Figure 25.

The Rape of the Sabine Women,

by Giambologna, 1582

Edmonia would have seen Giambologna’s serpentine masterpiece at the Loggia dei Lanzi soon after she arrived in Florence. The mannerist style was at first considered “anti-classical.” Photo by Ricardo André Frantz.

A Famous Quotation

The Virgin Mary holds center stage among the Church’s most powerful images. She is legion in Rome’s souvenir shops, customary in and outside buildings. Her portrayal is glorious and symbolic of modern miracles of faith. The constant reverence can be hypnotic in its effect.

Edmonia focused on her own ideas. As described by Anne Whitney and in the press, some of her Madonnas were more complex than others were: with child, at the cross, or embellished with a crown, angels, cherubs, flowers, etc.

There was little chance of encouragement from Protestants like Anne. Protestants were “heretics” according to the Church, which tolerated their presence in Rome. They tolerated in turn, but they feared the power of the Church, its politics and teachings. Some cheerfully relieved their anxiety by sneering, for example, that the Catholic

Catechism

deleted the commandment against “graven images,” making up for it by splitting the last commandment to achieve an even ten. Protestant artists turned to museums honoring ancient pagans rather than the religious icons that were everywhere else in Italy.

Edmonia could not deny her Calvinist schooling, her African connection, or the patronage of American Protestants, while she carved saints for English and other Catholics. The Protestant emphasis on personal Bible study blossomed in Edmonia’s vision of Hagar

.

Asked one day by the

Revolution

about her life-size

Hagar in the Wilderness,

she replied, “I have a strong sympathy for all women who have struggled and suffered. For this reason, the Virgin Mary is very dear to me.”

[352]

This particular quotation has echoed through passages about Edmonia ever since. Notice how she – or was it her interviewer? – changed the subject from Old Testament Hagar to Mary of the Gospels. At the time of the interview (1871), Edmonia reveled in the resounding success of her

Hagar

the prior year. Thus, the shift seems to be artful rather than arising from the moment.

Read by suffragettes rather than a race-related niche, the

Revolution

sighed about Hagar, freed slave and mother of Ishmael, but it invoked the Virgin Mary, a broader, more Christian symbol. Indeed, the New Testament theology of Saint Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and others cast Hagar as symbolic of non-Christians and of the “earthly” as opposed to the “spiritual,” thus excusing anti-Semitic racism.

One modern scholar, Allen Dwight Callahan, considered

Hagar

a critical interpretation of the Bible.

[353]

The

Revolution

interviewer, Laura Curtis Bullard, admired Edmonia’s work enough to collect her Hiawatha statues, but she skirted thorny theology.

Consider the story told in Genesis:

Abraham wished for a son.

His wife Sarah, who was barren, forced her Egyptian (i.e., African) slave, Hagar, to conceive a son with him. They called the son Ishmael.

With divine help, Sarah later bore Abraham his second son, Isaac. She desperately regretted Hagar’s child. According to custom, a man’s first-born son inherited everything. Sarah’s child would have nothing.

Sarah demanded Abraham banish Hagar and her child into the wilderness.

He did. Hagar and Ishmael soon faced doom.

And the water was spent in the bottle, and she cast the child under one of the shrubs.

And she went, and sat her down over against him a good way off, as it were a bow shot: for she said, Let me not see the death of the child. And she sat over against him, and lift up her voice, and wept.

[354]

Who could deny the profound despair of this moment? Hagar was exploited, abused, and cast out with her child. Her tale of woe inspired artists for more than two hundred years.

Hagar returns in the New Testament Epistle to the Galatians, a text attributed to Paul of Tarsus. American slave-owners had used portions of Galatians to command their captives to obedience. Ironically regarded on occasion as the apostle of freedom, Paul was the ‘patron saint’ of the master class before the Civil War. His biblical mandate sanctioned the return of runaway slaves.

Literate, devout slaves in Massachusetts had challenged Paul’s interpretations before slavery ended there. Who can serve two masters, God and man?

It is likely Edmonia encountered such discussions. Having “become” a member of the slave race as a young adult, she must have given such ideas some thought. With Hagar, she tried to understand her new identity from the point of view of a freed woman.

In that light, read the new meanings extracted by Paul:

Nevertheless what saith the scripture? Cast out the bondwoman and her son: for the son of the bondwoman shall not be heir with the son of the freewoman. So then, brethren, we are not children of the bondwoman, but of the free.

[355]

Moved by a struggle for souls, Paul argued against the offspring of Ishmael hundreds of years before the birth of Islam. He seems to define the true people of God as excluding the offspring of slaves. He taught that Abraham’s legacy must be never be bound to Hagar.

Edmonia could not accept Paul’s logic. Four million members of the African race in America were children of slaves. Yet they were accepted as Catholics and Protestant Christians. She had the blood of slaves.

She must have prayed for inspiration.

One day muse struck home. Hagar came anew. In her mind’s eye, Edmonia glimpsed a Genesis scene ignored by Paul:

And God heard the voice of the lad; and the angel of God called to Hagar out of heaven, and said unto her, What aileth thee, Hagar? fear not; for God hath heard the voice of the lad where he is.

Arise, lift up the lad, and hold him in thine hand; for I will make him a great nation.

[356]