The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (22 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Hearing of Edmonia, he sniffed another scoop. The success of a colored sculptor was the kind of sensation that he knew sold papers. He went to her studio in Rome, a photographer in tow.

Edmonia mused at his outrage that some male artists had not done her the courtesy of a visit. The

San Francisco Chronicle

eventually reported her sardonic note on their rudeness: “But that didn’t trouble me much.”

[306]

Beyond Charlotte, Hatty, and the sculptors of Florence, European artists, such as Shakspere Wood, an Englishman, Isabel Cholmeley, and the aging Italian professor, Adamo Tadolini,

[307]

befriended her. Tadolini had worked closely with Canova, the genius of neoclassical marble, even sharing a studio that is today part museum, part restaurant.

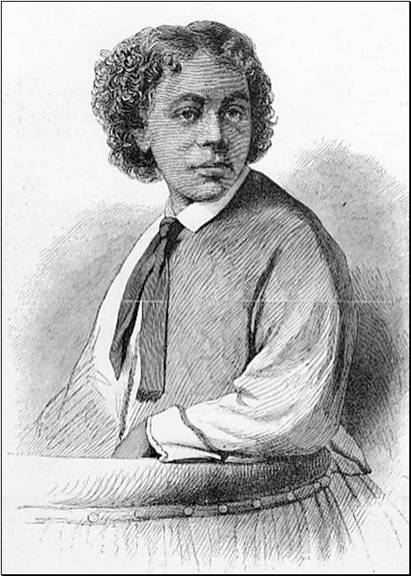

A year after the Paris expo and his visit to her studio in Rome, Leslie published a striking engraving of the young artist (Figure 20), surely based on a photo.

[308]

We believe it to be the earliest surviving portrait of our subject. The exposure of several minutes required by the crude technology could not capture a good smile, impulse, or other “Kodak moment.” Thus, the frozen pose fails to convey the charm that often captivated her interviewers as they took in the mixed race features that fascinated them.

Wreford had noted, “Whilst her youth and her colour claim our warmest sympathies, Miss Edmonia Lewis has a very engaging appearance and manners. Her eyes and the upper part of her face are fine; the crisp hair and thick lips, on the other hand, bespeak her negro paternity.

Naïve

in manner, happy and cheerful and all-unconscious of difficulty, because obeying a great impulse, she prattles like a child and with much simplicity and spirit pours forth all her aspirations.”

[309]

A year earlier, Tuckerman had offered a similar note: “In her coarse but appropriate attire, with her black hair loose … and with her large black sympathetic eyes brimful of unaffected enthusiasm.”

[310]

Leslie’s

also illustrated the romantic

Wooing.

By the time they appeared, three full years had elapsed since she left Boston. She needed to return to mend fences and to engage her new American fans. As the only “colored sculptor” and praised by critics, she was gathering interest.

Figure 20. “Edmonia Lewis, sculptor,” ca. 1867

Music Lessons

At Oberlin, Edmonia learned the basics of music at no extra cost. In addition to hymn singing, concerts brought the secular music of Handel, Mendelssohn, and Rossini. Boston offered similar fare. In Rome, she enjoyed the opera. As popular entertainment, opera was as “common as oil and wine, and nearly as cheap.”

[311]

Edmonia loved music so much she started lessons in Rome. As a hobby, her music endured in the shadow of her art. Surviving references are ambiguous, denying details even to the most diligent researchers.

[312]

Women of the day often sang, played harps, lutes, and keyboard instruments of all sizes. The piano, invented in Italy, was the instrument of female choice in America. Edmonia was so tiny, her hand probably failed the octave and such basics of most full-size stringed instruments.

Her commercial rise let her enjoy other aspects of color-blind Roman life. By mid-1868, she flaunted her success in an open carriage, eye-catching and proud, riding through the crowds at the ancient Pincian gardens and villas that overlook the streets of Rome.

Mrs. Child, fretting about Edmonia’s lack of manners, was further horrified by word her music lessons.

[313]

She was certain Edmonia lived on charity and simply burned through every dollar she received. Having felt real poverty, she was the penny-conscious author of America’s first book on household management:

The Frugal Housewife

(1828).

Edmonia’s recreation was modest compared with most of the expat colony – elaborate dinners, servants, carriages, and stables of horses. Edmonia was not part of their social swirl and churn despite occasional invitations.

It seems likely that Isabel and Hugh Cholmeley were responsible for Edmonia meeting Franz Liszt, virtuoso pianist and composer. Liszt was the musical fireball of the century. He was also notorious for his love affairs with titled, married, and rich women. In his adolescence, he had dreamed of becoming a priest. Retiring to a monastery in Rome, he wrote religious music, taught, and studied theology. He dressed in clerical robes but was not entitled to hear confessions or to say Mass.

Impressive in his tailored black cassock, Abbé Liszt welcomed Edmonia. His love for the Boston-made Chickering piano, with its patented cast-iron frame, could have been a topic of their conversation.

Charles Chickering

himself delivered one to Liszt in 1867 after it won

a

Légion d'Honneur

in Paris. The piano-maker’s offices were quite near Edmonia’s first favorite statue.

Charlotte liked to say Liszt was “always acting.”

[314]

In her words, “It is sinister, the mouth when he smiles curves up like a half moon and he looks like a devil. When he sits down to the piano, his face instantly becomes divine.”

Even so, his harmonic adventures, pianistic flourishes, and intimidating fortissimos could thrill and mesmerize. In a chamber setting, where listeners sit an arm's length or two from performers, the ferocious percussion of his large hands on the Chickering must have been electrifying.

Edmonia modeled his profile for a marble bas-relief. Images of famous people were her stock in trade. A medallion would not offend her best friend, Isabel, who was so proud of her bust of him. Edmonia spoke of visiting Liszt and hearing him play when American reformer Frances E. Willard visited her in 1870. Willard admired the Liszt medallion along with her portraits of other Americans.

[315]

Edmonia’s new circle of fashionable Catholic friends could provide a feeling of community and a spiritual home. While their gatherings were similar to Charlotte’s, she probably did not feel so much a conversation piece. She was a member, and she decided to return the welcome.

Isabel Cholmeley and Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, Liszt’s platonic companion, both offered to stand godmother at her adult baptism. Edmonia chose Isabel and took two sweet baptismal names – Maria Ignatia.

[316]

Coming Out

For years, Edmonia had protected her Catholic roots against a Protestant world intolerant of the Roman Church and its members. Her harmless deception must have hardened under the Yankee orthodoxy that prized snipes at the pope and his followers. It was not for some time that she openly traced her link to the Jesuits.

[317]

In February, Anne Whitney revealed to her sister that Edmonia had joined the Church. With a sense of shock and betrayal, Anne rationalized that the turn was more practical than spiritual.

[318]

The local Protestant pastor was reputedly more interested in hunting foxes than in tending his flock. Because the Papal government did not allow ‘heretics’ to hold services in Rome, the nearest Protestant church endured outside its walls in an old granary near the hog market. The unattractive location was surrounded by filthy streets and harsh odors.

Anne also let her sister know that Edmonia was succeeding as a sculptor.

[319]

Yet, she remained coldly critical, considering Edmonia’s skills as crude as her turn of faith.

Professing decency, she wrote that she wished to help her, but Edmonia had rejected her advice. Thoughts of carving Catholic icons made Anne squirm as she bristled with superiority, calling them rude and wanting in elementary knowledge. In her view, Edmonia’s resistance to her advice stemmed from a fear of accusations that she let others create her work.

While they exchanged cordial visits occasionally, Anne’s envy mired her in denial of Edmonia’s advancing skills. To Anne, Edmonia preferred to blunder on in her own way.

No longer a beginner, Edmonia was not about to reveal her other mentors to Anne. She refined her craft with informal advice from Hatty Hosmer, Isabel Cholmeley, and the Tadolini tribe of notable sculptors.

Rogers, Powers, and other artists in Italy often made fun quoting coarse visitors’ ignorant comments that bore out the biblical motto about pearls before swine. Rather than joke and sneer, Edmonia preferred to blow up. As a colored woman, telling tales about rich white folk could only draw trouble.

Anne, however, had no such limits. In a letter dated Apr. 3, 1868, she sniggled to her sister how a pair of Americans insulted Edmonia as they entered her studio. One wrote his name in the guest book. The other, seeing Edmonia’s dark skin, objected and refused to enter.

Edmonia had been away from the United States for over two years by this time. She was on her own turf, and she made the most of it.

She glared at the loud one and scratched out the name. She told the visitors, she would not have any name in her book that is a disgrace to anyone!

Putting down the pen, she gnarled her hand into

il mano cornuto

(hand with horns)

.

In Italy this was a rude gesture. With forefinger and pinky extended like horns, it is popular today at rock concerts. She jabbed it at them, as she cursed and chased them out.

Anne, a witness to the rebuke, thrilled with delight and commented how funny she was.

Adding to her successful Longfellow line, Edmonia turned out images titled

Hiawatha, Minnehaha,

(Figure 21 and 22) and

Minnehaha’s Father

. Their faces lack exotic features, but fans of the day considered their hair and clothing true to her Native American past.

Figure 21.

Minnehaha,

1868

Figure 22.

Hiawatha,

1868

The marble busts shown above belong to the Newark Museum, Newark NJ. Photos by Uyvsdi.

Where other artists sold only marble, she sold plaster busts portraying her ancestors and heroes, as she did in Boston, and marble miniatures (for example the bust of Miss Waterston). This lifelong policy served hero worshippers excluded by art forms that favored wealth. She sold them by mail as well as at shows and in her studio.

Quick to cast, plaster was affordable. Her plaster portraits appear dressed (Figures 6, 28, 44, 45, 46), suggesting a sound grasp of purse-related taste. Most of her marble busts are classically nude.

The New Emancipation Statue

About the same time that Edmonia joined the Catholic Church, Elizabeth Peabody arrived in Rome as Charlotte Cushman’s guest.

[320]

She and Charlotte undoubtedly reveled in the recent YMCA triumph. Beshawled and breathless from climbing Rome’s hills, she stopped at Edmonia’s studio where she pored over the guest book and cards left by visitors. Americans, she noted with dismay, left the fewest traces.