The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (21 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

In 1870, Louisa May Alcott and her sister would lodge at 2 Piazza Barberini, corner of Via Sistina, an easy walk to both art districts. San Nicola competed with Margutta for art buyers. It had advantages beyond proximity to the railroad terminal and Story’s celebrity. Behind the old Armenian church (for which the street was named) the Capuchin monks lived above famous ossuary crypts. Prosperous visitors roosted in a large new first class hotel, the Costanzi, which boasted a lift and dominated the street at no. 10. In 1873, the

New York Times

declared it “the grandest hotel of the Eternal City.”

[285]

Just above the hotel, at no. 8, then at no. 9, Edmonia flourished from fall 1867 through the 1870s.

[286]

Beyond the bevy of art-seekers, her new studio had an edge over the forbidding gate of her old Canova space and the up-stairs studios of so many rivals. An expensive glass door invited passing tourists to peer inside, perhaps to enter. For rivals and keepers of old biases, it was one more cinder in their resentful eyes.

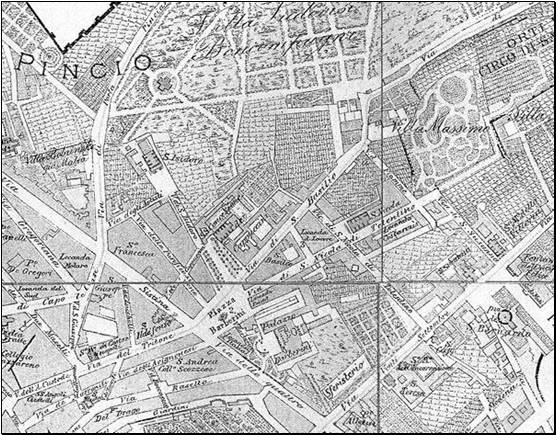

Figure 17. Via di San Nicola da Tolentino art district

Taken from a map published by the man who owned much of the Gardens of Sallust, this detail shows the Via di San Nicola da Tolentino (running northeasterly from the Piazza Barberini up to the Via di Santa Susanna) before the area was overtaken by development. The Vicolo crosses the Via at a right angle, connecting it with Via San Basilio and more art studios. The rail terminal lies off the map to the east. Note the “Palazzo Barberini” and the Hotel “Locanda Costanzi,” across from the “S. Nicola” church. This map is also online at http://www.edmonialewis.com/san_nicola_art_district.htm.

L’

Exposition Universelle

Meanwhile, Emperor Napoleon III aimed to outdo the English expo of 1862 with a new world’s fair. French entries were soon followed by a flood from England, Italy, Germany, etc. For American artists in Rome who were disappointed with their government’s refusal to ship their marbles, national pride was just another patronage. Five years earlier, William Story achieved fame while letting the Pope pay his freight to London. Rumor had it he and other sculptors planned to enter under the Roman flag again. In the end, they quietly opted out. Hosmer proclaimed her patriotism by sending her

Sleeping Faun

to the U. S. section at her own cost. Only Margaret Foley, who sent some clever medallions, appeared in Paris as an American under the Roman flag.

[287]

Edmonia went to Paris as a tourist. It was her best chance to evaluate other artists on neutral ground. In Rome, she avoided most men’s studios as they did hers. Here such limits did not apply.

By the time she finished scouting, she could coldly compare the samples on display with her own work. So many statues were larger than anything she had done. Flawless white marble dominated, with bronze in significant evidence. She saw subjects and poses far outside her experience. The most prestigious entries from Italy reflected its cultural focus on themes classical and symbolic, marks of a private education and upper class membership.

In his official review, journalist Frank Leslie emphasized the historic and classical.

[288]

He considered French artists, whose works outnumbered the others, more realistic. In the United States section, he singled out Hosmer’s entry for enthusiastic praise. Many of her colleagues had sent nothing.

More important for Edmonia, the rigors of style had started to fall away to fresh ideas from the New World. In particular, J. Q. A. Ward cast non-Caucasian men in bronze – a life-size

Indian Hunter

(a man and dog that now stalk New York’s Central Park) and

The Freedman,

(Figure 18) created in wartime 1863 to symbolize the end of slavery in America.

Ward was one American sculptor who had no problem with “Congo.” He carved a lone black man (often traced to a celebrated classical fragment,

The Belvedere Torso,

[289]

) with no reference to Lincoln. His images could turn and burn in her mind. She might also have read the critical appreciations quoted in Tuckerman’s compilation published that year:

“Here is the simple figure of a semi-nude negro, sitting, it may be on the steps of the Capitol, a fugitive, resting his arms upon his knees, his head turned eagerly piercing into the distance for his ever-vigilant enemy, his hand grasping his broken manacles with an energy that bodes no good to his pursuers. A simple story, simple and most plainly told. There is no departure from the negro type. It shows the black man as he runs today. It is no abstraction, or bit of metaphysics that needs to be labeled or explained. It is a fact, not a fancy. He is all African. With a true and honest instinct, Mr. Ward has gone among the race, and from the best specimens, with wonderful patience and perseverance, has selected and combined, and from this race alone erected a noble figure—a form that might challenge the admiration of an ancient Greek. It is a mighty expression of stalwart manhood, which now, thanks to the courage and genius of the artist, stands forth for the first time to assert in the face of the world’s prejudices, that, with the best of them, he has at least an equal physical conformation.” And the author of the “Art Idea”

[290]

] says of this work: — “It is completely original in itself—a genuine inspiration of American history, noble in thought and lofty in sentiment. It symbolizes the African race in America, the birthday of a new people in the ranks of civilization; we have seen nothing in sculpture more soul-lifting or more comprehensively eloquent. It tells the whole sad tale of slavery and the bright story of emancipation. The negro is true to his type—of naturalistic fidelity of limbs; in form and strength suggesting the colossal, and yet of an ideal beauty, made divine by the divinity of art. It is to be regretted that the cost of this work in bronze must necessarily limit the number of copies, as it should be seen and possessed by the great mass of the people. Why cannot we have copies in clay-colored material? It would fill a great want in our available sculpture—something to educate the people, to point out the legitimate province of that dignified art, of which Mr. Ward is one of the most illustrious and honored disciples.”

[291]

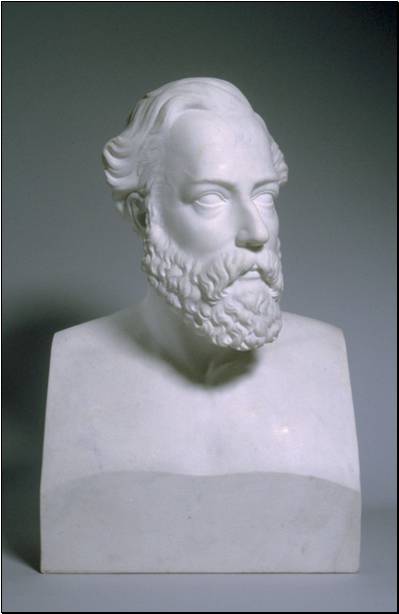

Figure 18.

The Freedman,

by J. Q. A. Ward, 1863

During the Civil War, Ward first displayed a plaster cast of his radical image at the New York Academy of Design. It generated considerable buzz in the

Boston Transcript,

the

New York Times,

etc. In 1867, he sent a bronze copy to Paris. Photo courtesy: Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Alice Keys Hollister and Mary Eva Keys.

Edmonia’s problem was no longer survival. It was ambition. Ward’s successes must have sharpened her hunger to join in. Returning to her new studio, she addressed her Emancipation task and unleashed edits that had fermented with Chapman’s critique and the sights of Paris.

She fired off a reply to Chapman, promising that she had embraced her comments.

[292]

Too excited to wait for the photo that showed her improvements, she prayed the print that followed would be effective. When it was ready, she sent it to Mrs. Chapman, Mrs. Child, the

Freedmen’s Record,

and possibly others.

Edmonia could have shriveled away if she had paused to wait, the long silence between letters sure to aggravate doubts. Humility and paranoia could tease: Wasn’t pity the basis of the London articles, of Tuckerman’s praise, of sales to tourists, and Cushman’s patronage? “Considering her antecedents” is one of the ways Mrs. Child put it.

[293]

Anne Whitney, who privately complained that a large, ignorant class of buyers misled the colored sculptor, considered it indulgence favoring her color.

[294]

Then good news as cooler weather took hold. Presumably, some Bostonian advised her how the first of her commissioned busts had triumphed! Her

Dioclesian Lewis

(Figure 19) appeared at the A. A. Childs & Co. (not related to Lydia Maria Child) gallery on Tremont Street.

Unitarian Rev. John T. Sargent praised it in the

Boston Transcript.

The

National Anti-Slavery Standard

reprinted his remarks, noting he owned a copy of Edmonia’s

Shaw,

[295]

but omitting that it was a gift of the artist.

In Philadelphia, the

Christian Recorder

reported, “it is not only an accurate likeness, but she has given the attitude and expression of the physical educator most happily.”

[296]

Boston’s

Commonwealth

hailed her insights, concluding, “it is not the doctor of the platform but the doctor of social life, in a subdued and thoughtful moment and so the best rendering for friends and pupils.”

[297]

Moved by such admiration, the owner showed the bust in New York.

[298]

There, the

Herald of Health

sang the praises of the natural likeness and the young sculptor.

[299]

Someone ordered a second copy in marble.

The excitement continued as the YMCA announced

The Wooing

was on its way.

[300]

Once again, Bostonians liked her work.

A colored newspaper in San Francisco later underscored the significance of the donation: “strong evidence of the capacity of our race for the higher branches of art, and a refutation of the slanders … of our natural inferiority.”

[301]

In December, her

Shaw

bust graced an elaborate memorial service in Boston for the late governor John Albion Andrew alongside marble busts by Brackett, Powers, Sarah Clampitt Ames, and Thomas R. Gould.

[302]

At some later date, the “Y” would extend its admiration with a copy of her

Hiawatha

bust.

[303]

For Edmonia, the success must have recharged her optimism. Yet, still no word from Mrs. Chapman.

For Charlotte, Rome was wearing thin. She and Emma decided to take the next summer in America, where she hoped to reinvigorate herself. She must have felt old, for she added five years to her age on the ship’s passenger list.

[304]

Figure 19.

Dioclesian Lewis,

1868

[305]

Modeled in Boston in 1865, the first marble copy was made in Rome and dated 1867. Photo courtesy: Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Founded in 1855, the

New York Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

was the sensational mass medium of its day – a weekly forerunner of the great tabloids and magazines of the twentieth century. Leslie could divine popular interest with the sense of a shark for fresh blood. During the Civil War, he satisfied curiosity about the battlefield with woodblock engravings. Later he portrayed the capture of Jeff Davis dressed as a southern belle in hoopskirt, sunbonnet and calico wrapper – a slander according to southern critics.