The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (25 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Miraculous hope rose from bleakest despair! According to interviews in the

Art-Journal

and the

Chicago Evening Post,

Edmonia froze her image squarely in this moment of deliverance.

[357]

Breaking again with stylish deadpan to furrow intense feeling into her subject’s brow,

[358]

Hagar

steps up to embrace her future. As Callahan put it, “Paul’s tortured typology leaves off precisely where the implicit, lapidary exegesis of Lewis begins.”

[359]

The scene is a stunning metaphor, easily recognized, a powerful symbol of hope and a prayer for colored Americans. Slave masters forced them to conceive children, then they set them adrift in an uncertain and hostile element. Praise God, the Angel is here. Fear not! He will make good His promise. Amen.

Hagar

also reflected Edmonia’s own experiences as a victim delivered by rescuers beyond her ken or control. Like the

Freed Woman

and

Forever Free,

it expressed Edmonia’s positive faith in herself and hope for the people she represented.

Excited by her insight, she plunged into the delight of creation around the time of Peabody’s visit, her ‘coming out’ as a Catholic, and the landing of

Forever Free

in Boston.

[360]

Her special affection for her

Hagar

must have won her the admiration and sympathy of friends in Rome. She could not wait to put it into marble. Hugh Cholmeley, perhaps at the urging of Isabel, advanced the money. Sharing enthusiasms, they must have convinced themselves it would quickly find a buyer while Edmonia awaited payments from Boston and New York.

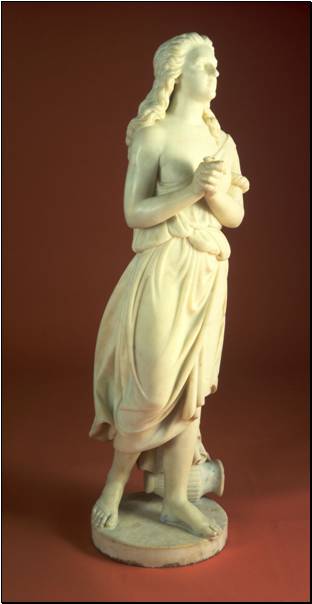

Figure 26.

Hagar,

this copy 1875

As the third and final iteration of the symbolic freed woman, the success of

Hagar

had a deep meaning for the artist. Not apparent in this view are the emotional furrows in her forehead. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

Money

By many accounts, the art market failed its 1868-69 season. As the New Year turned and Carnival began, financial distress forced Edmonia to rethink her situation. Her growing inventory of expensive marble carvings lacked ready customers. For many visitors, her blood, her exotic story, and her potential were always more interesting than her art.

[361]

She urgently reached out to old friends.

After a long silence between them, she sent Mrs. Child a photo of

Hagar

and begged her for a review.

Child took grim satisfaction, no doubt, in learning her warnings had come true. Turned as bitter as bile by the

Freed Woman

and

Forever Free,

Child would not fall prey to her own weakness a third time. She scolded Edmonia “not to be in such a hurry to do

large

works, depending on subscriptions to pay for the marble.”

[362]

To friends like Sarah Shaw, she could say nothing good about a

Hagar

that lacked an ideal Greek anatomy: “[It] looked more like a stout German woman or an English woman than a slim Egyptian, emaciated by wandering in the desert.” With hardened scorn, she ruled that Edmonia could never be anything but “a very good copyist.”

Edmonia’s troubles took her beyond private letters. She went to the press. The Boston weekly,

Commonwealth,

reported, “Edmonia Lewis, the coloured sculptress in Rome, is in straightened circumstances, and has had no orders for several months, though Rome is usually full, even with Americans. She desires to sell her Hagar, reserving the right to exhibit it, in which case she will come with it personally to the United States.”

[363]

Newspapers across the country relayed the urgent appeal.

An English bank in Rome, Freeborn & Co., served English and American artists. It was located near the Spanish Steps and loaned money at a greedy twelve percent interest.

[364]

It was probably the Freeborn agent, Ificelo Ercole, who advanced enough cash to cover the costs of

Forever Free, Indians in Battle,

and the marbles consigned to New York. Multilingual and a gossip, he commented to Anne Whitney that nobody was buying art despite crowds of tourists. Such an omen of default surely spurred his panic for repayment. Piling on, Hugh Cholmeley also demanded return of his money.

In Boston, the managers of A. A. Childs & Co. tired of hosting

Forever Free

after more than a year. They readied the work for auction. The $400 minimum bid they posted with Edmonia’s unhappy accord would cover Sewall’s expenses and their sales commission but not her bills for marble.

[365]

Visualize Edmonia at the age of twenty-five as the economy interrupted her crusade, her business, and her fascination with forms and ideas. She suddenly needed to learn about market cycles, legal practices, and the nature of pals who put money before friendship.

Why would she have planned to repay her good friend, Hugh, before selling

Hagar?

She counted him and Isabel as best friends. The sum was not large, given the Cholmeley resources. Heart pounding, mind in turmoil, she must have feared her saints and Caesars, her casts and tools, and even her beloved

Hagar

would vanish for pennies like old shoes at a beggar’s auction.

Could they, would they do that? It was a nightmare. Income was uncertain, living expenses unavoidable. She probably could not even offer a small sum or plan a schedule of payments. She apparently could not reach her brother, thousands of miles away. “Sometimes,” she later said, “times were dark and the outlook lonesome.”

[366]

The winter of 1869 must have been her darkest since her Oberlin beating.

Hearing rumbles of distress, Anne headed for Edmonia’s studio, then withdrew in fear of Edmonia’s fierce temper.

[367]

Significantly, because it reflects a mutual distrust, Edmonia did not confide in her, despite their long history and the nearness of their studios.

As smug as Mrs. Child, Anne spun her

noblesse

to her sister, claiming that it was only the prospect of offending that had restrained her from sharing her poor opinion of

Hagar

with Edmonia and telling her not to put it in marble. She, of course, lacked Edmonia’s sense of mission and adventure. She never carved marble without an order.

Others did help. According to Anne’s sources, Shakspere Wood, the English sculptor who arrived in Rome in 1851, came to the rescue.

[368]

We found no ready confirmation of this, but Wood had helped Hosmer with business details. That he was English might have helped with Hugh if not Ercole as well. It is possible he bought the IOUs, allowing Hugh to move on and Ercole to relax. The conflict may have eased, but Edmonia was still hopelessly in debt.

Had she lived today, Edmonia might puzzle over Henry James lumping her into “that strange sisterhood.” She had ample occasion to curse her isolation – and her own hand in it. Yet, she chose to swim alone, as she had done in her last year at Oberlin, rather than drift into backwaters of low regard and drown in self-pity.

In December 1868, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had taken up quarters in Rome for the winter. He settled in the brand new hotel, the Costanzi, that rose high above Edmonia’s modest shop.

[369]

Naturally, he became the darling of Rome’s English-speaking high society. The bright-eyed, white-haired poet was more than a luminary in Edmonia’s eyes. He was her muse. He had inspired her most popular works and every one of the “sisterhood” knew it.

A clear mark of the exclusion Edmonia suffered, not one of her boosters in Rome thought to introduce her to the author or to even point him to her gallery of Hiawatha figures right next to his hotel. Not Hatty, not Anne and Abby, not Abbé Liszt and Princess Carolyne, and certainly not the Storys ever paused for Edmonia’s sake as they dined him in their apartments and toured him about the city.

A year earlier, Charlotte had roused friends to send

The Wooing

to Boston’s YMCA. She sent more of the Danish artist’s plaster composers to the Music Hall. For Edmonia, however, she and the rest vanished like butterflies in the wind. Their behavior suggests that word of Edmonia’s gaffe with the Sewalls must have scorched Charlotte’s ears when she visited Boston in late October – if not earlier.

[370]

Edmonia was as out of fashion as a Confederate dollar. Only Elizabeth Peabody, back in America and ever loyal, expressed concern about her financial crisis. As a reader of the

Commonwealth

and seemingly aware of the social gulf between Edmonia and the sisterhood, Elizabeth felt she had to relay her alarm to Charlotte in Rome!

Alas, Charlotte had left Rome in May after finding a lump in her breast. She eventually responded from England with a remarkable sham: “I ever do all I can for her, as does Emma Stebbins.”

[371]

If the stresses of error, isolation, debt, and a sluggish season were not sufficiently maddening, there was also the conflict with Margaret Foley, the former mill worker turned sculptor whose studio sat halfway between the Piazzas Barberini and di Spagna.

[372]

Margaret sulked and Edmonia spit “a good deal of aboriginal venom” in a feud so bitter that gossips called it “war.” Letters fail to give details, but events suggest ample cause beyond the ill will common between Irish and colored Americans.

The self-taught Margaret had created a memorial portrait of Col. Shaw in Rome after his death. She must have felt thwarted to find a colored newcomer had swamped the ready market in Boston with the Shaw family blessing. In late 1865, she returned to Boston for a year and rented the very studio Edmonia had just vacated. Mr. Longfellow gave her a sitting there. Back in Rome, a critic called her profile of him “exquisite workmanship, and true to life.”

[373]

It was a highlight of her collection, but critics extolled Edmonia at far greater length. Now Edmonia bathed in crowds of prime retail traffic while Margaret languished in a marginal location.

Margaret also raged against Charlotte Cushman, who had brought her to Rome in 1862. In Charlotte’s reply to Elizabeth Peabody cited above, the actress expressed anguish over “Miss Foley’s trepidations and prejudices against me.” Was it that Charlotte had favored the “colored sculptor” with her fund-raising patronage and not the Irish cameo artist?

Her back to the wall, Edmonia dug in. She desperately needed a new sign of success. Capturing the author of her mythic lovers could ease her pain. An excellent portrait might redeem her in Boston, where Longfellow was held in the highest esteem.

She put her low status to work. Never introduced, she could scrutinize him on the streets of Rome while remaining as anonymous as a city pigeon. She caught glimpses as he strolled, waited for a carriage, or went to lunch or dinner. She likely stalked him in front of his hotel, down the street, and as he headed for G. P. A. Healy’s studio around the corner.

[374]

With skills learned as a child in the woods, she evaded his notice. Longfellow was likely preoccupied with learned figures of speech – describing Rome for example, “like king Lear staggering in the storm and crowned with weeds.”

[375]

Skilled and sure, her fingers flew at the clay – maybe the last scrap at her disposal. Although the man was always fully clothed and wore a fine hat outside, she made him as hatless and bare-chested as the masters of Olympus.

[376]

It was the portrait look most often adopted by sculptors who followed the ancient Greeks.

Longfellow was, after all, a member of the modern literary pantheon. In the ever-wishful idiom of the day, the depiction could show him as more god than mortal man.

Still, she surely longed to meet him. He would leave Rome after Carnival like every other tourist.

In the end, their introduction was by chance, as remarkable as it was humble. Longfellow’s youngest brother,

[377]

whose report Anne Whitney captured with scant detail, browsed into her studio. There was no mention of the damp rags that must have covered the soft clay. Nor was there much of their conversation.

Edmonia likely recognized him as a member of the Longfellow party. She probably greeted him and asked if she could help. Did she invite him to view the bust and then remove the cloth? Or, was she wily, slipping the cloth away and then silently guiding her prey like a rabbit to a trap?

No matter. To his utter surprise, the Longfellow brother suddenly came eye-to-eye with the poet’s stern visage. It stared back at him, seizing his attention, spurring his excitement. Thrilled, he dashed next door and fetched the family.

As they admired her work, perhaps they discussed

Evangeline,

[378]

the Civil War, the Fields, and the many other people they knew in common. No doubt, some conversation turned on the Longfellow-inspired array in her studio. It is likely she offered him his pick.

[379]