The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (10 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

In spite of its connection to a market ripened by wealth and sophistication, the best neoclassical sculpture could stir the masses. Hiram Powers’ astonishing marble

Greek Slave

– nude, white, and as perfect as any Venus – called national attention to the political issue of slavery in 1847. A publicist put together a pamphlet and took this, the first celebrated life-size nude female figure by an American sculptor, on a four-year tour. Its commercial success made Powers, who had grown roots in Florence, Italy, rich. It made the traveling showman even richer.

The statue’s emotive sizzle – depicting a sexually desirable Christian maiden about to be raped by heretical Turks – mixed visual pleasure with moral horror. It drew the curious as well as serious critics by tweaking consciences, insinuating that American slave traders were barbaric rapists. In a sonnet about it, Elizabeth Barrett Browning rhapsodized: “From God’s pure heights of beauty against man’s wrong!”

[87]

Crowds fell silent in a daze of race-reversal, frowning and later expressing dismay.

That Hiram Powers, born to poor farmers, lacked the class credentials of Hatty Hosmer, William Story, the Greenoughs, and others escaped Mrs. Child’s square and neurotic view.

Intent on memorializing Shaw, Edmonia sought photos of him. Mrs. Child was a possible source. She spoke of a life-long friendship with Shaw’s parents, of knowing Robert since his infancy. Could she help? Some time after Child’s visit to her studio, Edmonia revealed her intent in a letter asking Mrs. Child for help.

[88]

The request precipitated a storm brewing in the dark recesses of Child’s psyche. She flatly refused. The idea was a shock, beyond the permissible, not to be considered. Her objections went beyond the raw skills demonstrated by crude medallions. She shuddered at the thought of this rough youngster trampling hallowed memories.

Largely unspoken was her fear that others would blame her for allowing her sympathy to overrule her good sense. The Shaws were among her oldest friends. She knew they wished for a memorial far grander than this novice could provide.

Child stewed over this for years, her inability to reconcile her feelings about Edmonia disturbing her letters like a recurring nightmare. In her recall, she at first had urged Edmonia to simply abandon any thought of memorializing the Shaw’s son. It was too ambitious, not a job for a newcomer with no experience, no qualifications, and no reputation.

Becoming more critical as Edmonia persisted, Child told her to get a real job. Study in your spare time. Learn the basics before attempting such projects.

Eventually, the older woman raged. Soon, they were hardly speaking.

Edmonia paid no heed. With the single-minded passion of Juliet for her Romeo, she worked her clay and begged photos. She did not argue, did not apologize, did not pause to discuss and negotiate. The perseverance that Child had admired wedged them apart.

As the weather warmed, Edmonia found herself caught between a clay muddle and an elusive memory.

[89]

She appealed to Brackett for help. He turned her away. At Anne Whitney’s suggestion, she went to Robert Ball Hughes. He had created America’s first marble statue decades earlier and his was the first bronze statue cast in the United States. She spent a hot summer day traveling to his home outside the city. While Hughes seemed agreeable, his family did not permit him to go into town because of his fondness for drink. Then, Anne recommended John Crookshanks King. His portrayals of Daniel Webster, John Quincy Adams, and Ralph Waldo Emerson had established his considerable skill. It was useless. Edmonia trembled with desperation as she reported another failure.

In the full rut of ambition, she finally asked Anne to be her teacher. It was her last hope. Anne agreed, but not before asserting class superiority to a friend, criticizing Edmonia’s honesty and housekeeping.

Wigwam No. 89

In the coolness of October, two matriarchs of reform lumbered up the stairs to Edmonia’s studio. Longtime friends and political allies, the plain Child and the stunning Chapman had invitations to see the new work. They surely chattered as they climbed, the noise giving a cheerful luster to their mission.

Writing for the public, Child hid her discord with Edmonia. She dramatized instead her superior sensibilities: “Being aware how difficult it is to attain to excellence in sculpture, and, in addition to deficiency of early culture, [Edmonia] had the double disadvantage of being a woman and colored, I did feel somewhat sorry she had undertaken a task so formidable. But she seemed to have such strong faith in the power of perseverance to conquer all obstacles…”

[90]

Claiming tact to her reading public, she fibbed about her stern advice: “I had not the heart to mention my misgivings to her.”

Edmonia must have wondered what to think when her mentor sneered at her plan and urged her to get a job. She was in Mrs. Child’s debt. Child had encouraged Edmonia at first with publicity, sending customers, and helping secure subjects. The injunctions that followed guaranteed to be millstones of futility. If Edmonia submitted, she would ever be the pupil – with real achievement endlessly out of reach.

In light of such demands, Edmonia’s sacred pursuit of Shaw’s image took on a character of defiance. As she formed the clay, she must have pondered the practical terms of her dilemma. Opposing Mrs. Child’s advice might mean a break. She did not have the words to convince the more articulate woman how the Shaw project gave her life purpose and meaning.

In the end, the slippery stuff was more convincing than any words, more persuasive than anything Mrs. Child could say. Complying with her touch, it encouraged her to proceed. Edmonia was as resolute as her heroes. If her portrait of Shaw came up a success, so much the better. If it failed, so be it. She would not give up without a struggle. She would not put it to a debate. Only she would pay, in the end, for her decision. Few knew how her backers helped her. Anne Whitney, probably Edward Bannister (who was memorializing Shaw in oils next door), perhaps even Maria Chapman and others also gave encouragement and loaned photos. Never publicized, they would not stand trial with Edmonia’s rise or ruin – as Child would.

Envision the sixty-two year old sedentary writer and colleague only four years her junior as they climbed the stairs of the Studio Building. The dusty stairwell must have seemed warm compared to the breath-fogging morning outside. For Child, three flights up to a dreaded showdown must have been unwelcome exercise. Chapman was likely unaware of or indifferent to Child’s drama. Autumn garb weighed heavily. When they reached Edmonia’s floor, their faces would have been shiny in the glow of a skylight. They paused at the landing to collect themselves. Exchanging looks, they walked toward Edmonia’s tin sign. Chapman gave two quick raps.

Upon hearing them on the stairs, Edmonia probably had risen. Instantly, she swung the door wide.

They blinked, going from gloomy hall to sunlit room.

Silence.

Mrs. Child squinted, frozen. Mrs. Chapman raised her hand, perhaps holding a white handkerchief and half hiding her face, and glided in with graceful authority. With two noiseless steps, Edmonia swept the damp cloth from her work. She stood back to study their reactions. Her game face as stony as the Sphinx, she focused her mind on Mrs. Child.

Would Child still oppose her work – or would the work regain her trust? The stillness of the moment hardly did justice to three elevated pulses. For an eternal moment, no one breathed. Mrs. Chapman circled the clay figure in slow motion. Who would speak first, taking responsibility for all to follow?

Suddenly, a flood of noise drowned all worries. A stunned Edmonia barely heard the words, the sounds, the sighs, ooos, and ahs. She barely saw the happy faces in the daylight from the window. They circled and circled, nodding and crying out. Look, look! Oh my!

The waiting was over. She finally exhaled.

Profoundly moved, both visitors smiled through tears of joy. Both had known Robert since childhood. Both had mourned his death.

Child captured the fleeting sentiment of this moment for the

New York National Anti-Slavery Standard,

but not until the praise of all Boston drowned all lingering qualms. Three months later, her readers could read, “I was very agreeably surprised. She indeed ‘wrought well with her unpractised hand.’ I thought the likeness extremely good, and the refined face had a firm yet sad expression, as one going consciously, though willingly to martyrdom, for the rescue of his country and the redemption of a race.”

[91]

Implying a sacred moment, she continued,

And the clay needed moistening, she took water from a vase near by and reverently sprinkled the head. The sight of that little brown hand thus tenderly baptizing the `fair-haired Saxon hero’ affected me deeply, and I saw that it had made a similar impression on Mrs. Chapman who was with me. We both felt that there was something inexpressibly beautiful and touching in the efforts of a long oppressed race to sanctify the memory of their martyr. Indeed, I think that the deep feeling of admiration and gratitude, which the artist felt for the young hero whose lineaments she traced was one great reason why she succeeded so well.

Aloof insofar as organized religion, Child believed in the spirit world. She reported that Edmonia confided to her in suitable terms, “If I were a Spiritualist, I should think Colonel Shaw came to aid me ... for I thought, and thought, and thought how handsome he looked when he passed through the streets of Boston with his regiment, and I thought, and thought, and thought how he must have looked when he led them to Fort Wagner, and at last it seemed to me as if he was actually in the room.”

[92]

Deeply impressed, Child later added, “I appreciated the feeling of gratitude and admiration which led her to

wish

to do it, and which prompted her to keep kissing the clay while she worked upon it.” Such sentimentalisms melted Child’s heart. She confessed her full support, even if she would change tack one day. “Assuredly, this is the spirit with which an artist ought to work. I believe nothing is done truly well, in literature or art, unless it is wrought with intensity of spirit.”

[93]

Figure 4.

Col. Robert Gould Shaw,

1864. Plaster

Edmonia’s portrait of Col. Shaw was her breakthrough. She portrayed him in the neoclassical style, as bare-chested as an athlete of ancient Greece. Augustus Marshall, whose studio neighbored Edmonia’s, took this photo of the bust. She sold one hundred copies of the bust at $15 each as well as copies of the photo. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

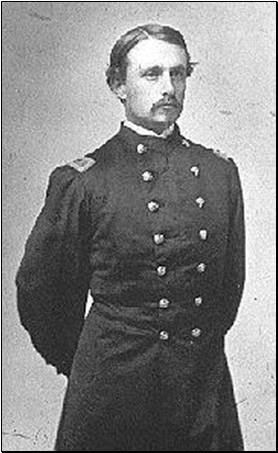

Figure 5. Robert Gould Shaw in uniform, May, 1863

Perhaps this photo of Shaw in uniform guided Edmonia’s portrait. Photo courtesy: Boston Athenæum.

Unauthorized and unexpected, Edmonia’s bust upset the Shaws’ plans, just as Child had anticipated. Only a large public memorial would satisfy their grief. After the war, they began to plan in earnest. William Story, the local celebrity living in Rome, won the commission but then lost interest as fund-raising floundered.

[94]

The stunning bronze relief seen today on Boston Common was not commissioned until the 1880s and not completed until 1897.

Perhaps Shaw’s mother wished Whittier had written a poem. He was too ardent a pacifist to praise the Civil War, although he supported its abolitionist underpinnings. More than ten years later, he explained to Child, “

I have longed to speak of the emotions of that hour, but I dared not, lest I should indirectly give a new impulse to war. For his parents I feel that reverence to duty and forgetfulness of self, in view of the mighty interests of humanity. There must be a noble pride in their great sorrow. I am sure they would not exchange their dead son for any living one.”

[95]