The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (12 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

The other female character, Hilda, a pretty, pale, talented copier of paintings, enjoyed the liberty of Rome without worry. She epitomized America’s Puritan legacy, her virtue symbolized by the eternal flame of the Holy Virgin of which she, a “heretic” Protestant, was unbelievably the keeper. More important, she came and went as she pleased without raising a single eyebrow.

The Marble Faun

– coming on top of Hosmer’s visit, her doctor’s advice, and her loneliness – spelled out the special lure of Italy for Edmonia. A later passage stalled any argument to the contrary. Hilda was a poor orphan! “[Her] gentle courage had brought her safely over land and sea; her mild, unflagging perseverance had made a place for her in the famous city.”

[116]

Unflagging perseverance? Edmonia’s resolve separated her from others. Child made a point of it. In a single sentence, Hawthorne’s splendid imagination could not have framed Edmonia’s future more deftly. Was it not a sign?

and More Commissions

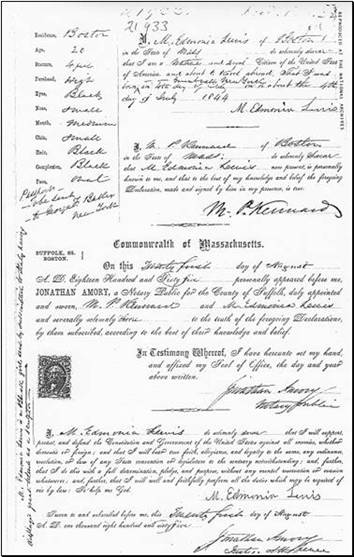

As snows turned black with soot and melted away, Mrs. Chapman sought her out and asked her to make her portrait (Figure 6).

[117]

Moved by Edmonia’s success and likely disturbed by her sickness, the older woman must have devised this direct way of helping. The sittings created a chance to encourage her in a motherly way and to know her better. Edmonia would turn to her in future. When finished, Edmonia cast the completed image in plaster.

A year later, Child saw it displayed it in Chapman’s drawing room near the Shaw bust.

[118]

In a hypercritical mood, she wrote to her friend, “Mrs. Chapman’s bust, taken from

life

, is a tolerable likeness, with her refined beauty left out.”

[119]

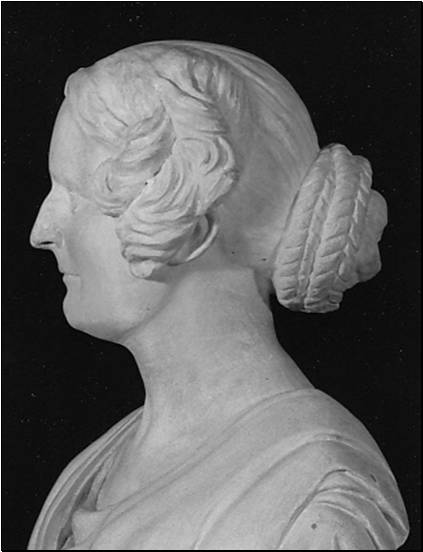

Compare the photo of the bust of Mrs. Chapman, which demonstrates Edmonia’s talent before she went to Rome, with the portrait below it.

Figure 6.

Maria Weston Chapman,

1865

We believe this to be the earliest surviving example of Edmonia’s sculpture. Compare it with the picture below. Photo courtesy: Tufts Free Library, Weymouth, MA. Photo: Harry B Henderson Jr.

Figure 7.

Maria Weston Chapman

[120]

Spring weather opened more doors. Edmonia won commissions for busts of three reformers: abolitionist physician Henry I. Bowditch, Dr. W. W. Hebbard,

[121]

and Dioclesian Lewis, a pioneer advocate of exercises for women.

[122]

Her clay image of ‘Dio’ Lewis so impressed his friends that his brother acquired a plaster copy and others commissioned her to carve it in marble. When Edmonia exhibited her

Hebbard,

the press called it a “decided success.”

[123]

Continuing sales made it possible for her to realistically plan to travel to Rome.

As Edmonia planned her exit, Mrs. Child chimed in with more unwanted guidance. She beseeched Edmonia to forego working in marble for two or three or even four years.

[124]

She recommended working in stucco molding for architects, instead. It would be better use of her time while she studied sculpture in off hours. Not to throw a complete damper on Edmonia’s ambition, Mrs. Child proposed she keep sculpting in her spare time, “… and if in the course of years, she produced something really good, people would be ready enough to propose to put it into marble for her.”

[125]

Wanting to seem thoughtful, she added, “I have also thought of woodcarving as a means of subsistence.”

Subsistence? Edmonia likely considered Mrs. Child’s remarks well intentioned but out of touch. It was the Shaw dispute all over again – but not deserved. The

Shaw

bust had proven something. The priority had to be art and the artist. Income would follow or she would quit.

Everyone prayed to end the War. To some, the sin of slavery called for mortal retribution. In his second inaugural address, Lincoln himself puzzled whether God required “every

drop of blood

drawn with the

lash

… be paid by another drawn with the

sword

.”

Finally came reports of colored troops singing “John Brown’s Body” in the streets of Charleston. Richmond fell soon after. The war was over! As rebel leaders fled, they robbed Confederate gold and set the city on fire. The next morning, colored men, women, and children cheered in the streets. Slaves were truly freed.

Before the warring states could adjust, the Good Friday assassination of Abraham Lincoln shook the world. Bitterness and talk of swift justice overshadowed Easter celebrations and dominated the weeks that followed. The murder focused Edmonia’s own inner fury. Working from engravings, she swiftly formed a medallion portrait of the late president while the funeral wended its way by rail to Springfield, Illinois.

[126]

Survivor’s guilt must have troubled her. For more than a year, she had been dropping in at the liveliest room in the Studio Building. Number 8 was headquarters of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society. Hannah E. Stevenson, a wealthy Roxbury abolitionist, and Ednah Dow Cheney, a writer interested in art, always welcomed her. They praised her bust of Shaw “a remarkable success, both as a likeness and as an ideal work.”

[127]

With great optimism for the potential of former slaves and future generations, they organized aid and education. Raising funds and sending teachers south, they aimed to “make another New England.” Their Society preached, Every freed slave could be a scholar. Most wanted to be.

Their teachers were supposed to be products of a New England education. Edmonia was not, but volunteers were scarce. The standard soon gave way, allowing colored men and women among the teachers. The committee accepted her, and she headed to Richmond accompanied by the daughter of her landlord, a colored girl about the same age.

[128]

They left Boston in early July and returned a few weeks later.

Scant records exist of what she did. She saw, no doubt, more African Americans than she had ever seen before. Thieves stole their trunks, leaving her and her friend with only the clothes on their backs.

[129]

Fortunately, her loss was limited to clothing. The irreplaceable plaster casts remained in Boston.

Beyond that, sources tell only that Edmonia, staying with a Richmond family, suggested they name their next child after a famous abolitionist. Wendell Phillips Dabney, who eventually became a distinguished newspaper publisher, later attached some irony to his name, saying, “I am the only colored person living who doesn’t think himself an orator.”

[130]

Through all the uncertainties of wartime, the lure of Rome surely found a firm place in her heart. It would be her personal solution to the limits of America.

Half-mentor, half-censor, Mrs. Child must have puzzled Edmonia. No New Englander helped – or troubled – her more. Mrs. Child took two steps back after every step forward.

On the other hand, seeing a viable bust of the young Shaw in clay over her objections must have been a shock for the aging writer. Her grim vision of Lewis with a penknife, first disclosed in a private letter,

[131]

hinted her fury. It presaged her own use of a sharp tool. In March 1865, Mrs. Child had published an expanded version of her

Liberator

interview in the short-lived

Detroit Broken Fetter.

Repeating her figure of speech, she wrote, “[Edmonia’s] indomitable spirit of energy and perseverance … would undoubtedly cut its way through the heart of the Alps with a pen-knife.”

[132]

Mrs. Child had assaulted the helpless proxy for Lewis with a saw and cut out its heart. The brutal attack and cool admission to Shaw’s mother (who must have read it with horror) showed her frustration and sense of superior entitlement.

Months later, before sailing, Edmonia traveled the twenty miles to Wayland to say goodbye. Entering Mrs. Child’s modest parlor, she looked around for her bust of Shaw. When her eyes fell upon it, her shock must have been unmistakable. It was damaged!

Child had a ready excuse: “Wishing to make it look more military, I sawed off a large portion of the long, awkward-looking chest, and set the head on the pedestal again, in a way that made it look much more erect and alert.”

[133]

Edmonia, known to have a sharp temper, must have called on the most stoic of her ancestors to keep a cool reserve. With studied reserve, she whispered, “Why didn’t you tell me that before I finished? How much you have improved it!”

Mrs. Child was no artist. Certainly a proper “master,” mentor, or critic would just make suggestions or ask questions. Who would ever take a carpenter’s tool to a cast made by Powers, Hosmer, or Story?

But why shouldn’t Child be angry? She had unselfishly publicized Edmonia’s work and even offered up grandmotherly wisdom. The young ingrate had ignored her pleas to leave Shaw’s memory alone. In a silent, emotional impulse, Child assaulted the helpless plaster in the privacy of her home. Having a proxy for Edmonia, she cut out its heart.

Now, on the eve of separation, she used her crime to test Edmonia’s character. To her credit, Edmonia sustained her poise. She had, after all, begged for criticism. If Child had reservations when she saw the statue in Edmonia’s studio, she could certainly keep a secret. She, as well as Chapman, Hosmer, Bannister, Whitney, and others had all seen the bust before Edmonia put it into plaster. Any of them might have assessed the length of the torso.

Edmonia then spied a small album with four photos of Col. Shaw. Looking through it, she could no longer contain herself. She exploded. Oh, how you could have helped me with these pictures! How I could have made such a better likeness!

Relating the episode to Shaw’s mother a few months later, Child played down the outburst with a sniff. “She was a little

fâchée

[French: “angry”] with me, because I did not send her any of the photographs of Robert.”

[134]

The French embellishment seems to assert the superior class she shared with her reader.

In a mood of appeasement, Mrs. Child gave Edmonia a beautiful silk gown before she left. It eased the tension. Both women were the same petite size. Someone had stolen Edmonia’s wardrobe in Richmond.

By mending hurt feelings, the gift renewed Child’s license to set harsh limits. Satisfied with the visit, she wished Edmonia well and cautioned once again not to put anything into marble unless she had an order for it. Known for plain dress, Mrs. Child made little sacrifice by clearing her closet of idle clothing.

Edmonia could assure her she had orders for several busts of various people. One was for a marble copy of Col. Shaw from his sister. When she executed it a year or so later, she embraced Child’s savage critique. A comparison of photos reveals a reduction in the length of the chest. Good marble is, of course, far more expensive than plaster. Shortening the chest should have made a practical step toward profitability.

She also claimed commissions for marble busts of her heroes, Abraham Lincoln and John Brown.

[135]

Another was for the late Horace Mann, Miss Peabody’s brother-in-law. As an educator, he had reformed schools all over the country.

Merchant Martin Parry Kennard often went abroad to stock his store with fine furniture and other expensive goods. He volunteered to help Edmonia with travel arrangements. When he helped her to apply for a passport, he wrote in the margin, “M. Edmonia Lewis is a

Black girl

sent by subscription

[136]

to Italy having displayed great talent as

a Sculptor

.”

She planned to pick up her papers in New York.