The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (42 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Figure 45.

Senator Charles Sumner.

Plaster, painted terra cotta, 1876

The fragile bust above was destroyed in a 1974 tornado. Photo courtesy Wilberforce University.

Figure 46.

Bishop Benjamin W. Arnett.

Plaster, painted terra cotta, 1876

Photo courtesy: Wilberforce University.

Two visits to New York’s Shiloh Church and Rev. Dr. Henry Highland Garnet fifteen years apart suggest matched portals in time. The first marks her entry as an unknown artist in 1863, the second her exit as a celebrity in 1878. She had gone for his counsel when the church was located at 61 Prince (near Lafayette) Street. She was then a mere student with an odd gleam in her eye. The second time, she was so famous that the

New York Times

published advance notices of a grand reception at 140 Sixth Avenue (near Dominick St.) and then sent a reporter.

[673]

The highlight of the evening was the unveiling of her life-size bust of the first hero she ever portrayed, John Brown. Having donated her time and talent, she proudly presented it to the aging preacher, now a famous colored orator.

As a young man, Rev. Garnet supported Brown’s forceful approach. After the war, Congress invited him to deliver his views as it passed the Thirteenth Amendment. As the first colored American to speak at the Capitol, he prayed for equal justice – even for the poorest, weakest citizens – in a memorable address.

[674]

The Shiloh celebration had the nature of a lasting farewell. Never again would she be so applauded, so revered, so recognized in person. Rev. Garnet shook with emotion as he spoke of John Brown and recalled Edmonia’s history, how she came to him for advice, how he blessed her and sent her on her way to Boston, and the successes that followed.

The

New York Times,

the

New York Herald Tribune,

and other accounts provided a rare picture of her at a critical point in her life, having won unique battles in a tortuous struggle. Their lofty tone also betrayed the pervasive bias she found so suffocating. She spoke “very frankly and unaffectedly of her early struggles and privations,” reported the

Times,

unfortunately without details. It was more intent on her blood:

a fluent talker when the theme is such as to arouse her enthusiasm, she has something of the habitual quietude and stoicism of the Indian race.... In person she is rather below medium stature, and strong and supple rather than delicately made. She leans slightly forward in speaking, pronounces slowly and deliberately, and has a trace of sadness of both races in her manner, not withstanding her assured artistic success.

Unscripted responses from the pews would have been more enthusiastic, saluting her travails and celebrating her triumphs. Together they all sang John Brown’s favorite hymn, “Blow Ye the Trumpet, Blow,” and the Civil War anthem, “John Brown’s Body.” Someone read a poem, “The Dying Cleopatra,” probably the ode by Thomas S. Collier that Edmonia included in her book of Centennial reviews.

The

Times

reporter sought to explain why she refused to stay in America. After 1869, Edmonia did not publicize specific insults to her color, but for years she made no secret of her permanent return to Europe. She politely described the frustrations that kept her abroad:

“I was practically driven to Rome,” said Miss Lewis. “In order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.” With the little money she could raise, Miss Lewis set out for Rome, where at last she found herself in a real republic. Miss Hosmer became her fast friend and defender, and the American colony at Rome, having left their race prejudices at home, received her kindly. Her origin only served to give emphasis to her phenomenal powers. [King] Victor Emmanuel, the Marquis of Bute, sovereign and nobility, vied with each other in doing her honor. She has executed several busts of John Brown and other celebrities for European customers and has been received as an honored guest in the first circles. All this time she was cogitating her first great ideal work – the “Dying Cleopatra” – a work that in some sense typifies the attitudes of both the races she represents.

[675]

Amplifying remarks reported years before in the

Graphic,

Edmonia said she did not wish to live in a society that could not help but isolate her: “They treat me very kindly here [in the United States] but it is with a kind of reservation.” Skipping the bumps, threats, insults, and denials of public service, she cited only comments and stares that she did not have to tolerate in Europe. Generations of colored artists followed her path abroad.

Her fans wished her god speed. They appreciated how she sought redemption peacefully, through her art. She made her own opportunities, confronting ignorance with dignity where she could. Nearly a century before tiny Rosa Parks

[676]

held her seat on a Montgomery bus, Edmonia endured hostile glares, threats, and other abuse as she stood with her work in space tacitly reserved for white male artists. Living proof that talent favors no race, no gender, no class, no religion, and no ethnic origin, she commemorated her heroes. She celebrated her heritage. She moved across the color line with grace.

Having realized a bittersweet version of the American dream, she bid farewell forever. Her ship sailed on the tide, south to clear the harbor, then eastward. She could not, would not, live with Jim Crow.

And he said: “Behold, your grave-posts

Have no mark, no sign, nor symbol.”

– The Song of Hiawatha

Chippewa parents may wait before naming a child. They often start by naming a girl for a flower. Years later, a new name or nickname might signify some development. Based on the English form of her Indian name “Wild Fire,” linguist Basil H. Johnston suggested Edmonia’s mother called her

Ishkoodah’

[ish-GOOD-day] for the Cardinal Flower

(Lobelia cardinalis L.).

[677]

There is no Chippewa word for “wild,” he said.

It is a timely choice for a July baby. The summer bloom in the slender shape of a trumpet makes it a favorite of hummingbirds and butterflies. It also has powerful medical properties, containing both a sedative and a stimulant. Indians have used it to treat bronchial spasms, syphilis, intestinal worms – even as love medicine – and a variety of other ailments.

[678]

Parts of the plant are smoked, used to make tea, or placed nearby for effect. Abuse can cause great discomfort, coma, and loss of life.

We do not know for certain that she first bore the name

Ishkoodah’.

She met Canada’s “first anthropologist” in 1864 at the Boston gallery exhibiting Whitney’s

Africa Awakening.

By this time, she had not lived with the Indians for more than ten years. Her Indian name, probably an idle question for her friends, was of professional interest to him. “Her Indian name was

Suhkuhegarequa,

or Wildfire,” he recalled years later.

[679]

The Chippewa word [pronounced zuck-KUH-ig-GAY-kway] literally translates to “fire-lighter woman.”

[680]

Rather than a literal, incendiary meaning, unlikely for the little girl who lived with Indians until she was eight years old, the name more likely meant to evoke the “People of the [fire-making] Flint” with whom she lived, played, and traveled as a child.

[681]

Presumably, she earned the Chippewa nickname by embracing Mohawk ways.

By 1882, Edmonia adopted

“Ishkoodah’”

as used by Longfellow in

The Song of Hiawatha.

We offer documentary evidence in her own hand (see Figure 47).

Ishkoodah’

can also mean “fire” or “comet.” Perhaps she pondered Longfellow’s lines:

“Filled with awe was Hiawatha / At the aspect of his father. / On the air about him wildly / Tossed and streamed his cloudy tresses, / Gleamed like drifting snow his tresses, / Glared like Ishkoodah, the comet, / Like the star with fiery tresses.”

As a source of awe, an exotic reference to

Ishkoodah’

the comet could serve the ambition of such a highly motivated, competitive artist. In Longfellow’s imagery, it was powerful, fascinating, and free. Splendid comets, gleaming and glaring as bright as the moon, promised mystical powers.

“Comet-years” were famous for good vintages of wine and grand tragedies of national moment. A two-tailed comet, so magnificent it was recalled for decades, appeared in 1843, perhaps a signal of her conception. A smaller but brilliant comet took the skies in 1854, near her teen awakening. A giant followed in 1858, as she decided to apply to Oberlin. Marking her adulthood in 1861, at the age of seventeen, she asked to be called Edmonia.

[682]

The unusual radiance of the comet that year provoked theories about the Civil War and thoughts of fearsome events in Europe: the abdication of a Holy Roman Emperor, the London plague, the death of a Pope. This was another night-sky event everyone talked about for years.

Is there a further connection between comets and her name? “Edmonia” was rare north of the Mason-Dixon line. Fewer than 0.003 per cent of 11.3 million American females answered to it in 1850, the census source closest to her birth date. Of its 259 Edmonias, only three of potential relevance appear – all born the same decade – all clustered in upstate New York.

[683]

The others lived over a thousand miles away, to the south and west. Edmonia Highgate, the daughter of a colored barber, was born in Albany NY the same year as Edmonia. She achieved notability as a teacher. The Highgate and Lewis families could easily have had associates in common. Edmonia Jackson, also colored, was born 1849 in nearby Troy. A white girl named Edmonia Hopkins was born the next year in Steuben County. Were there links?

To say the name references Edmond Halley cannot be proved. But then, Halley’s was and is the most famous comet. In 1843 and 1861, his name was in the news.

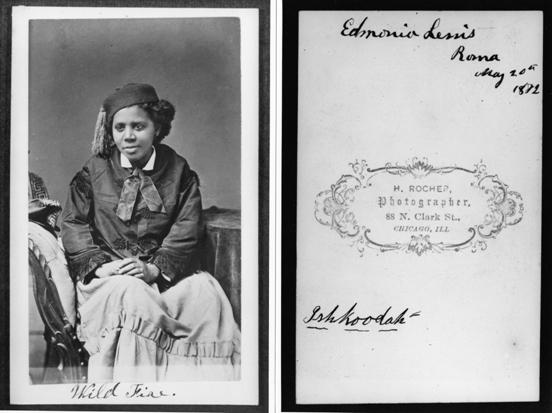

Figure 47. Autograph souvenir of Edmonia Lewis, front and back

This photo

carte de visite,

autographed “Edmonia Lewis Roma May 20

th

1882,” “Wild Fire,” and

“Ishkoodah´,”

came from the papers of her friend, Amelia Blandford Edwards. Courtesy: The Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford, England.

Denial or Denunciation

Public art in the City of Love embraced bare flesh and sensuality going back to pre-Christian times. While pious followers of the Reformation and popes from the time of Michelangelo demanded fig leaves, most Italians still considered robust breasts, buttocks, and male genitalia gifts of God – not Devil’s tools. No hint of shyness stopped the husband of a young model from pointing to an image of her raw beauty with spousal pride. Napoleon’s sister, Princess Borghese famously shed her clothes to pose for Canova at work on his

Venus Victrix

. Asked if she was comfortable, her memorable comment was, Why not? A stove kept me warm.

To some New Englanders, merely seeing nudity, even in stone, was somehow dirty. In his fiction, the prim Hawthorne explained, “An artist … cannot sculpture nudity with a pure heart, if only because he is compelled to steal guilty glimpses at hired models. The marble inevitably loses its chastity under such circumstances.”

[684]

Such frail Yankees must have shook with shame as they met banned truths in public gardens, museums, and piazzas. Yet they toured Rome and Florence with exceptional enthusiasm.

Not to be outdone, William Story beat the shrill drum of prudery while exposing breasts in his own works. He felt Canova’s

Venus

was “detestable ... a lascivious courtesan.”

[685]

An American at his studio carped, “there is not one naked among them.”

[686]

Henry James, Story’s biographer and apologist, eventually explained that Victorians demanded drapery.