The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (41 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

After the great fire of 1871, Chicagoans boosted their rebirth through popular expositions. They earned the nickname “Windy City” not so much for their weather as for their incessant self-promotion.

Before the Centennial closed, a representative asked her to exhibit

The Death of Cleopatra

in Chicago. She welcomed the proposal, feeling relieved of a great burden: what was going to happen to her masterwork? Maybe it would find a permanent home there.

Costs of shipping the large statue back to Rome were prohibitive. Where would she find a home for it? There were few possibilities. Art museums in the United States scarcely existed. The five-year-old Metropolitan in New York lodged in town houses. The Art Institute of Chicago was also in early development. Philadelphia already boasted two collections – the Charles Willson Peale collection housed temporarily at Independence Hall and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts – but Philadelphia was very conservative and, as noted, unfriendly.

[658]

Despite the admiring crowds, no one had offered to buy it.

Chicago had been wonderful to her. She would again see John Jones, now a Cook County Commissioner, and could count on his counsel.

She readily agreed.

Portraits in Rome

Edmonia celebrated her success by printing a book of her reviews from the Centennial.

[659]

She included a “sketch” of the love story and dramatic deaths of Antony and Cleopatra. In no way a poet of words, she followed William Story again, emulating his post-carving literary effort by taking passages from the popular Langhorn translation of

Plutarch’s Lives.

She changed the death scene, of course, to portray Cleopatra on a golden throne, rather than a bed.

Surely she sent the book to her brother, to Isabel Cholmeley in Venice, perhaps another to one of the Tadolini family. A copy in her studio would impress visitors; on the road, her fans. Only one copy survives to our knowledge, in the national library at Florence.

A few American visitors could still delight her, such as the AME Church minister who cared nothing about stylish art or religious difference. Intent on meeting her face to face, he sought out her studio, his first stop on arriving at Rome.

[660]

Thousands of faithful flocked to Rome for Holy Week each spring, creating a steady demand for religious themes. Other art sales suffered as fewer tourists came looking for artists’ studios. A new excitement in Paris had upstaged the neoclassical style and Rome.

Pope Pius IX died in early 1878. John Cardinal McCloskey, the first American prince of the Church, arrived too late for the papal conclave. At some point, he sat for Edmonia as she made his portrait bust.

[661]

Named in 1847 as the first bishop of the diocese that ran from Albany NY to the St. Regis Akwesasne Mohawk reserve, he must have been a most exciting subject.

Ex-President Grant, on a world tour, also agreed to a sitting. Asked if he liked his portrait, Edmonia replied, “Oh yes, but he didn’t say much; he is such a quiet man. He is the only president we ever had who doesn’t talk much. He will be the next president. I don’t know anyone who is better fitted for that position. I was invited to the grand reception given him, and I went.”

[662]

She probably hoped to sell many copies. Unfortunately, Grant lost the 1880 Republican nomination after thirty-six ballots.

Chicago’s recurring expo was about attracting tourists and selling hardware, from tool-making machines to reapers and plows. Ten thousand people poured in on opening day. Expo planners meant art and music to draw the general public and entertain wives and children who had no interest in engines and levers. The art committee, trying to raise the quality of exhibits, had banned portraits by local artists – upsetting them and their sitters.

Edmonia arrived in August 1878 with her bust of

President Grant

and the array she had showed in Philadelphia. Once again, she probably relied on John Jones.

Figure 43. Advertisement,

Chicago Tribune,

1878

Daily ads featured Edmonia’s

Cleopatra

with no mention of her color while news items reminded every reader.

[663]

As Edmonia held forth beside her work, some praised her. Others picked at any nit to express their misery.

[664]

A widely copied news item that called her “dark, short, and young” cited her noble patrons as it protested the abuse she suffered.

[665]

Others acknowledged her skill, recalling her 1870 showing of

Hagar

and railing outrage on her behalf. Some editors noted such annoyances at the Centennial. A letter writer summed up: “Notwithstanding the provocations to which Miss Lewis is subjected, she will prove herself more worthy of honor and fame than her heartless detractors.”

[666]

The

Woman’s Journal

ignored the race issue, preferring to romance its readers with poetry as it described the marble queen, “[in] the moment when, mounting her throne, and bidding her maids robe her in the finest garments, she touched the asp to her bosom.”

[667]

Suffering from kidney disease and semi-retired, John Jones could have shared his views on the state of civil rights with her. Reconstruction, mortally hurt in the 1874 mid-term polls, had finally fallen in a deal made after the most argued national election of the century.

In the 1876 national contest, Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote against the reform-spirited New York Democrat, Governor Samuel J. Tilden. However, Hayes won the Electoral College – barely, with twenty votes in doubt. To resolve the dispute, he traded civil rights for the office with a special commission rather than by vote of the Electoral College. Once in power, he pulled Federal troops out of the South, thus inviting violence and deceit to fill the void. This cynical pact stalled the march of civil rights for a long time.

Aging and stymied by political riptides sweeping away hard-won gains, John Jones and Edmonia must have thought about retiring. Much of their work would stand. Others could pick it up one day.

They both had changed the way Americans thought about people of color. Both upset myths of weakness. No one had forced their long-term successes on the public. The public had spoken – at least, outside the old South.

Yet, the public was changing in other ways. The future seemed bound to Jim Crow. As the last biracial Congress of the nineteenth century prepared to exit, it had passed the 1875 Civil Rights Act. Backed by the late Senator Sumner, the Act aimed for equal treatment in hotels, public transportation, and theaters. Soon it was in the courts.

When the Expo closed in October, Edmonia let

The Death of Cleopatra

remain in a weeklong Grand Bazaar to benefit the Catholic House of the Good Shepherd,

[668]

a shelter for abandoned women. Two years later, the Republican National Convention called the Interstate Exposition Building their “wigwam” as they honored Emancipation and eulogized Reconstruction.

After the expo, Edmonia slipped away to fast-growing Indianapolis, where former slaves accounted for a large but segregated public. Members of the Vermont Street Bethel AME Church had shown interest in her portrait of Grant. She showed it at the church while staying at a member’s home.

It was there she gave an affable interview to the two-year-old

Indianapolis News.

Its publisher was a young and ambitious Civil War vet who was keener on gaining a large circulation than in a whites-only pose.

When asked about the

Grant

bust, she told the

News,

“I shall see if the church people don’t want to subscribe enough to buy it. It would cost anybody else $300, but I will let them have it for a great deal less.”

[669]

Church members soon presented the bust to their retiring minister.

She breezed past her “wild” origins with a new tilt, more

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

than

The Song of Hiawatha:

“I guess I was just like Topsy,[

[670]

] I just growed up,” she laughed.

She announced a commission for a statue of Bishop Foley in Chicago. She was also “well acquainted” with Bishop Chatard, now head of the local diocese, having met him frequently when he was rector of the American College in Rome.

Of racist snipes, she said:

I never hear of them [in Rome]. Why, I am invited everywhere, and am treated just as nicely as if the bluest of blue blood flowed through my veins. I number among my patrons the Marquis of Bute, Lady Ashburton and other members of the nobility.

She offered this spiritual guidance:

Sometimes the times were dark and the outlook was lonesome, but where there is a will, there is a way. I pitched in and dug at my work until now I am where I am. It was hard work though, but with color and sex against me, I have achieved success. That is what I tell my people whenever I meet them, that they must not be discouraged, but work ahead until the world is bound to respect them for what they have accomplished.

In an article that editors picked up in rural Iowa and Pennsylvania as well as Boston, the

News

described her as “small in stature with the regular features of her race, and in color is a little lighter than the ordinary negro.” It went on:

Her eyes, however, are large, brown and sparkling, her forehead is broad and high, and her hair is allowed to fall over her shoulders untrammeled by bow or ribbon. She is a charming conversationalist, using the choicest language, shows a wonderful enthusiasm in her work, and speaks freely of her past life and future prospects.

Was this her last visit to America? She told the

News:

“I don’t know. The Chicago people have my

Cleopatra

still and want me to come back next year and exhibit it again. I may come back – I would like to and perhaps I will.”

Idle talk and circumstances frustrated art lovers who wished for a museum in Chicago. The Chicago Academy of Design had lost its home in the great fire and was headed for bankruptcy. Lacking other options, Edmonia left

The Death of Cleopatra

in storage at the Inter-State Exposition Building.

It had out-earned

The Battle of Gettysburg

– $2,947 to $2,690

[671]

– despite the painting’s top billing. At twenty-five-cents a head, it was a real achievement. Thousands of Midwesterners had seen her and knew she had created a fabulous work of art.

As she packed for Rome, she must have recognized she would never see the ailing John Jones again. They were sad at her departure. For Edmonia it meant the end of an ally in America.

Six months later, he died.

[672]

Many leading Chicagoans attended elaborate funeral services in his home. Her busts of

Brown

and

Sumner

decorated the mantle.

Longfellow

appeared between two windows.

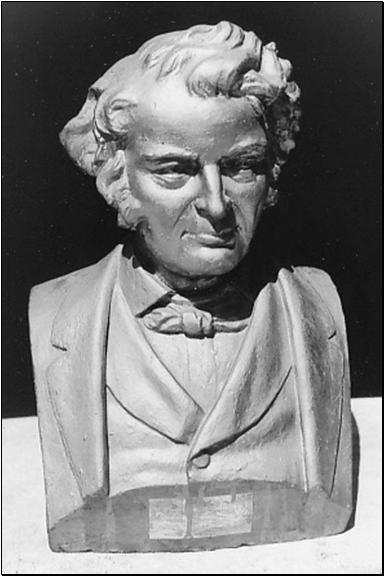

Figure 44.

John Brown.

Plaster, painted terra cotta, 1876

By using contemporary attire with the affordable plaster medium, Edmonia reached beyond the wealthy elite buyers of studious neoclassical marbles. Private collection.