The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (36 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

THE DEATH OF CLEOPATRA

– 1872 to 1875

Elements of Surprise

According to an 1876 interview, Edmonia started her

magnus opus

around 1872

.

[565]

Particularly intriguing is the four years of secrecy and deflection that followed. That year, the

Art-Journal

asked about the large draped work seen in her studio. If it were the life-size

John Brown

being readied for shipment to the Union League Club and already well publicized, would she not have promoted it as she had done before?

Instead, she left the writer puzzling as she slyly described “a large monument which persons of her own race have ordered from her for New England.”

[566]

The following year, she teased the

Daily Graphic

with threats of an anonymous entry. Even the last press coverage as she left Rome spoke only of her “two sleeping children, who have been gathering flowers, until wearied out they have fallen asleep, clinging to each other and holding fast their floral treasures in their chubby, tiny hands, with an expression upon their faces as if God and the angels were whispering to them tales of Paradise.” Nothing was said of its prize-winning quality or of the other statuary Edmonia had shipped. All of two-feet-tall, the carving was charming but dated and in no way sensational or rivalrous.

Edmonia often traveled six months out of twelve as she pursued marketing, missionary, and creative goals. The growing business required more time. She skipped her tour of America in 1874, perhaps to study Cleopatra in libraries and museums, possibly to concentrate on filling orders and accumulating cash. Massing her own clay, as described by Bullard in 1871, would have drained her energy and time. The next year, she employed nine assistants.

[567]

By the end of 1873, she claimed a work force of twenty.

At some point, she must have realized she needed someone to look after things while she was busy. A mature artisan who knew carving and carvers could also fill orders and serve customers while she toured. The man she hired presumably organized the work, knowing how to obtain supplies and labor, how much time certain tasks should take, and how to close a sale, arrange delivery, and collect money.

[568]

In 1873, James Peck Thomas was able to connect with her while she was touring America, presumably with the aid of her trusted manager.

If Edmonia confided her interest in Cleopatra, it would have been to Amelia Blandford Edwards, the English writer. She and Amelia had much in common. They were both never married, unrelentingly industrious, devotees of good music and art, highly competitive, and self-taught pioneers in occupations reserved for men. At some point, they became friends.

Amelia loved France and Italy. After writing about hiking the little-known valleys of the Italian Alps, she turned her full attention across the Mediterranean. At the time, she planned her classic guide to the Nile, which she illustrated and published in 1877. It is still in print today. She soon became a leading Egyptologist who thrived as she vied with men for recognition and control of resources.

In 1873, Edmonia had coolly thrown Amelia’s words in the face of the blood-befuddled editor of the

Graphic:

“[Amelia Edwards] once said to me, ‘You dear Edmonia, I think it is such a beautiful thing for you to come right away from those Indians and make such as stand as you have done.’”

[569]

Edmonia needed to decide what her Egyptian queen would look like. At the time, artists emphasized authenticity. Based on Cleopatra’s Greek ancestry, Isabel Cholmeley had rejected an Egyptian look a few years before.

[570]

William Story, on the other hand, cared little that the fabled vamp lacked even a drop of African blood. He clearly considered his

Cleopatra

to be a product of Egypt

.

[571]

Hawthorn, (as quoted above) for an image of his

own

imagination, used the word “Nubian” – often applied by others in the continuing confusion with Story’s statue.

Amelia was in a position to help Edmonia distinguish her work from Story’s and the rest. She could have recommended antique sources. It was a tactic suggested by Hawthorne via his fictional sculptor (but not apparent in either Hawthorne’s or Story’s

Cleopatra).

[572]

Used to working from photos, Edmonia now sketched from old coins and translations of Latin histories. Cleopatra had an eagle-like profile. Marc Antony, who adored his lady’s beak, had it stamped on the silver denarius and other coins. Seventeenth-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal quipped, “had [her nose] been shorter, the whole aspect of the world would have been altered.”

[573]

A technical challenge, the gown, could have taken days to work out. In contrast to Story’s plain, heavy folds, Edmonia rendered the garment with a form-revealing lightness and decorated it with ferns and roses.

The elaborate throne displayed a griffin, a fabulous beast of ancient mythology,

[574]

and other figures. Decorated for several perspectives, it outdid Story’s simple seat. In the arcane idiom of art, the cut rose at the subject’s foot hinted she died a lady.

Other details also seem historically authentic. Ancient manuscripts likely influenced the robe hanging over the arm of the throne and other features.

[575]

The two classic Egyptian figures supporting the arm pieces and descending as lion’s paws reflect Cleopatra’s twins (a boy and a girl) by Antony.

Making

John Brown

for the Union League Club had familiarized Edmonia with the problems of a seated figure. But a dying Cleopatra could not sit like the feisty radical. She likely mulled over a basic decision: death’s convulsions? Or, the final loss of muscle tone? They were different anatomical states.

As a Catholic, she had contemplated the death of Jesus on the cross many times. Crucifixion icons offered abundant models, often with head turning to its right. The head of Michelangelo’s

Dying Slave

(ca. 1513), which Edmonia could have seen at the Louvre, also went to its right.

She decided to turn the head to its left, falling back and resting on the throne. The left arm dangled, the right hand with the writhing asp on her lap. The pose of arms and head may remind one of Hosmer’s dozing nude (Figure 40), which gained fame just before Edmonia’s arrival in Rome.

[576]

Hosmer could have shared the technical how and why of her resounding success.

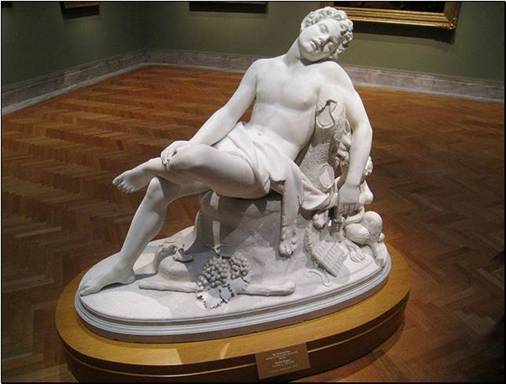

Figure 40.

The Sleeping Faun,

by Harriet Hosmer, 1865

Compare the head and arms of

The Sleeping Faun,

this copy in the Cleveland Museum of Art, with Edmonia’s

Death of Cleopatra

(Figure 42). As a neoclassical work, Hosmer’s dozer is often tied to the ancient, blatantly immodest

Barberini Faun

.

[577]

From the start, Edmonia must have known her macabre departure would grate against the emotional reserve and prudery of the time. How else could she excite the general viewer? The angry snake in the queen’s hand could have meant more to her as an eye catcher than as a primal emblem of death, sin, and eroticism.

Perhaps it was also an avatar of her own suppressed anger, but the thrust of our arguments suggests that getting attention was her priority.

She had never made a statue so large and expensive. Story’s

Cleopatra

is 55 inches high. Gould’s is 57. Hers stands taller, rising 63 inches, a competitive edge. Two tons of Carrara marble must have required another perilous loan. It was an enormous cost.

She must have agonized over borrowing again. Her creditors could hold up shipping until she settled her accounts with them. Consider who would give her the fortune she needed with no questions asked. The widow Cholmeley had remarried, giving up her short-lived independence, and gone to Venice. Lord Bute? He was a patron through clergy connections more than as a friend of her race. Edmonia could not begin to solicit donations from either of them without revealing her radical plan. It would be inviting disaster. Talk of it would excite people who would oppose her entry on principle.

What about the costs of her own travel and months of boarding in Philadelphia? Unlike other artists, it was essential for her to appear beside her work. More troubling, it was likely the expo managers would bar her and her work because of her color.

Magnificently bearded John W. Forney, ambassador from the Centennial Commission, reached Italy in March 1875.

[578]

If the Centennial had sent someone else or no one at all, our story might have gone another way.

Col. Forney relished power. He was a publisher, a politician, and a down-to-earth master of patronage. As the owner of a major Philadelphia newspaper, he was able to do favors, guide contracts, and hurt Philadelphians who crossed him. Originally a Democrat, he had turned Republican in order to back Lincoln’s antislavery bid for the White House. He became Secretary of the U. S. Senate during the Civil War. His newspapers had supported Andrew Johnson as Lincoln’s successor, but he became outraged at Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau Act. He threw his resources behind the impeachment team. When Johnson survived and called him a “dead duck,” Forney saw his political game at an end. He quit Washington and returned to Philadelphia. Now he claimed his

Philadelphia Press

as the official organ of the Centennial. His wife sat on the women’s executive committee.

Col. Forney visited American artists in Florence and Rome. After kowtowing at Story’s “superb”

Cleopatra,

he made the rounds of other artists and begged them to participate. In a memoir, he signaled Edmonia’s status by noting she had just sold a work for eight hundred dollars. If she revealed her secret, he made no mention of it in his report. As a progressive politician, he could have been keen enough to sense her goal and wise enough to keep her secret.

His impassioned editorial about the racial exclusions of the Centennial

[579]

leaves no doubt of his special interest in her as a person of color. His bid to her was unique. The Centennial rejected every other colored American. Her presence would show he retained power and that the gains of Reconstruction were not entirely defeated.

She must have made plans already. Perhaps he encouraged her to alter them. That year, she rendered another marble copy of

Hagar,

life-size and perhaps with the Centennial in mind. Did she know the Great Chicago Fire had consumed the first? She also made a brilliant miniature of Michelangelo’s colossal horned

Moses

based on the Catholic bible

.

[580]

The original can be seen at the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (St. Peter in Chains), Rome.

In the end, she decided to take only original works. Many people still believed women could only copy, never create. As a colored artist, she had more to prove than Harriet Hosmer, Anne Whitney, and the other sculptors of the “strange sisterhood.” She packed up her most successful originals: the prize-winning

Asleep,

the popular

Old Arrow Maker,

and its companion,

The Marriage of Hiawatha.

She also prepared affordable plaster busts of

John Brown

(Figure 44),

Senator Sumner

(Figure 45), and

Longfellow

(Figure 28), which she painted to resemble terra cotta.

[581]

All were for sale. All could be carved or cast and sold many times over. She targeted colored schools at Wilberforce, Hampton, Fisk, and perhaps others, in at least one case by mail.

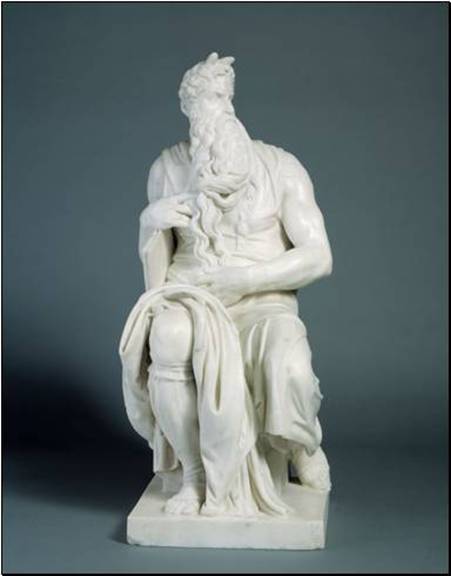

Figure 41.

Moses

(after Michelangelo), 1875

The timing of her copy of Michelangelo’s

Moses,

suggests she might have intended it for the Centennial. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred T. Morris, Jr.