The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (6 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Figure 1.

Urania,

1862

She drew this portrait of the heavenly muse of astronomy and astrology as a wedding gift for her college friends. An easily recognizable rendition of an antique statue

[47]

with her faint signature, “Edmonia Lewis,” it marks her beginnings as the historic artist. A candle wax stain appears to the left of the head. 14 ½ x 12 inches. Photo courtesy: Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin, Ohio.

Presumably at the suggestion of Douglass or Langston, she sought out Rev. Henry Highland Garnet for help. Garnet was known for his intelligence and his faith in the native ability of colored Americans. He ministered the Prince Street Church, later called Shiloh, long a leading center of activism in New York City and just a few blocks north of the railway terminal. New York City was second only to Philadelphia as home to large populations of blacks.

Focusing on her story, Garnet likely asked opinions of church elders. They must have been incredulous. Someone surely huffed, There is a

war

on! Others could have pointed out that Boston or Italy would serve an aspiring artist much better. Apologizing for not being able to do more, he wrote a letter to introduce her to William Lloyd Garrison. Putting his hand on her head, he sent her to Boston with a sense of awe: “God bless you, my little one; it is better to fail grandly than to succeed in a little way!”

[48]

In the course of her visit, she could have heard of the Colored Orphan Asylum. Far uptown at the time, it occupied a large, four-story building at 43d street, north of the city reservoir. The idea of hundreds of homeless colored children crowded together was something to ponder. They were the innocent outcasts of society. White orphans went west by the trainload for easy adoption. Any colored children with them returned, unwanted. The place was a symbol of who she was. It cast a long shadow of who she might have been. Her concern for such orphans would guide many of her choices.

Boston of 1863 was called the “Athens” of America: literate, worldly, rich, and – for the New World – quite old. As a country girl, Edmonia could not imagine where all the crooked little cobbled streets went or why. “It seemed as if I never went out to go anywhere, but what I went round and round….”

[49]

They were nothing like the modern wooden ways of Oberlin, where all the streets were straight and the corners turned true right angels.

Like its byways, Boston’s complexity posed a sharp contrast to the single-minded clarity that dominated her school. The ambitions of its economy had ruptured the conformist rigor of its founders. The result had modernized its ideas – but not its mores. Merchants more interested in profits than piety had rebelled against Calvinist self-denial. They embraced free will, free trade, tolerance, and reason while retaining a Puritan sense of decorum, hard work, and – for its Protestant majority – the rejection of most “popish” traditions. Members of the Episcopal Church (the former Church of England) flourished, overshadowing poor Irish and French Catholic neighbors. Spread via Harvard’s Divinity School throughout New England, Boston’s progressive theology questioned nearly every religious assumption. At the once-Puritan First Church, founded in 1630, liberal Unitarians doubted everything from the nature of God to ideas of human need and nature. An elite literary group calling themselves Transcendentalists preferred individuals’ intuitions to religious doctrines. Many admired old John Brown.

Fine art in Boston was once as scarce as gold in a debtors’ prison. Puritan forefathers had rejected the rich trappings of the state churches and monarchies that had persecuted them. They feared signs of opulence as distractions from spiritual purity. As Boston prospered, the newly wealthy sought to enliven spaces kept blank by two hundred years of sober restraint. They also nurtured an anti-slavery faction as zealous as Oberlin’s.

Yet, its call for the end of slavery in the South did not require equality at home. Boston lived by caste. At the top were the so-called Brahmins, wealthy families who traced themselves to the founders. At the low end: Edmonia Lewis. For room and board, colored newcomers were likely directed to the humble north slope of Beacon Hill, the side shaded from the winter sun and blocked from summer views of the public gardens. Known for its history of poverty, fugitive slaves, and brothels, locals called it “nigger hill.”

Franklin

Edmonia was on an adventure, seeking the famous Garrison and his anti-slavery newspaper. She soon entered School Street – a path to Garrison’s office. The school that gave the street its name was gone. In its place was the construction site of the new City Hall.

[50]

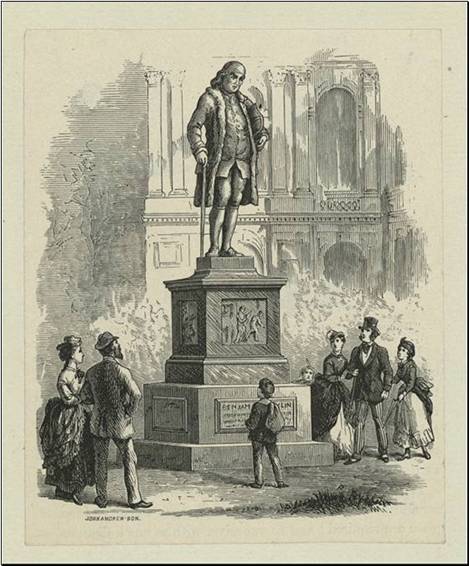

Passing the old stone church on the corner, she stopped short, frozen in her tracks. A massive green statue loomed before her (Figure 2). She had never seen anything like it! Excited, she stood for a moment, pulse racing, but otherwise as petrified as the towering figure. She stared up. Benjamin Franklin stared back, immune to the silent drama unfolding in the morning sunlight.

She would ever speak of the enchanted moment as lovers recall their first encounter. The feeling was intense, profound, the stirring of the inner child of her early years and the quenching of an aching thirst. The figure radiated unexpected power, and it became her personal hub. As she put it, “A certain fascination seemed always to direct my steps to that one spot, and I became almost crazy to make something like the thing which fascinated me.”

[51]

Overcoming their distaste for idolatry, Bostonians had rendered

Franklin

as a secular saint in modern dress – patriot, statesman, scientist, and printer. They installed the lifelike bronze statue in 1856, one of the first they erected for public viewing. It meant to remind the students at the Boston Latin School that he, too, was once a student there.

For Edmonia, it must have resonated with the childhood magic of holy icons at the famous Jesuit mission of St. Francis Xavier du Sault at Kahnawake. Its imported crucifix, paintings, bas-reliefs, and statues of saints,

[52]

are awesome. Its sister landmark Church of Stone of the St. Regis Akwesasne Mohawks is equally grand.

As an adult, she had never seen a three-dimensional image so massive. There were none at McGraw, none at Oberlin. She inspected the larger-than-life detail, the dimensions, the balding head, the long hair, the baggy chin, the fur trim on the coat, the wrinkles of face and fabrics, and the intelligence of the eyes – all illusions drawn from inorganic bronze. The totality of it affirmed awesome possibilities. Confusion gave way to a new power that galvanized her sense of purpose and settled her future. Like a spark on gunpowder, the sight provided thrust to her life trajectory.

Not far away, a bronze

Daniel Webster

(by Hiram Powers) had greeted visitors outside the State House since 1859. A marble

George Washington

(by Frances Chantrey), carved in 1827, rested inside. Once found, she surely added them to her routine.

Figure 2.

Benjamin Franklin,

by Richard S. Greenough

This eight-foot high bronze startled Edmonia in 1863. City fathers had unveiled it in 1856 with an elaborate ceremony. Courtesy: New York Public Library.

Walking on air like a woman in love, she found the offices of the

Boston Liberator

around the corner. Barely a foot taller than Tom Thumb and flush with outrageous ambition, she must have seemed incredible to the elegant Maria Weston Chapman.

Garrison’s chief aide bore herself with a deep sense of personal superiority. She was a descendent of Pilgrims and a founder of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. As a radical reformer, she once courageously marched through an angry mob. (Abolitionism was generally unpopular at first.) As a widow, she had relocated to Europe for her children’s education, and then returned, living in Weymouth. She could be imperious, dogmatic, and self-righteous. Her friends nicknamed her “Lady Macbeth.”

Edmonia likely saw nothing of Mrs. Chapman’s ambition, only the considerable charm she beamed at her young visitor. According to her oft-told tale, she explained she wanted to be an artist, to make statues like the one on School Street. She added that Mr. Douglass and Rev. Garnet had sent her.

Garrison, too, must have registered astonishment. People came seeking work, clothes, food, or a little money – not artistic training, not wishing to make statues. The mention of Douglass and Garnet in the same breath must have surprised him further. They differed on how to achieve their common goal, the elimination of slavery. Garnet, however, agreed with Douglass’s interest in Edmonia. His note asked Garrison to help her.

Garrison thought of Edward A. Brackett.

[53]

He had made portrait busts of John Brown, orator Wendell Phillips, and himself. His studio was quite near. Asking her to follow, he headed for the door.

With profuse thanks, Edmonia followed him. In his wake, she walked even taller. The warmth of that day would linger for years. She had met her destiny on School Street. The famous abolitionists of the

Liberator

had welcomed her. Mr. Garrison himself was leading her to someone who could help her. She would soon make a statue of her own.

The Artist

Edward Brackett’s starkly dead, life-sized nude, the

Shipwrecked Mother and Child,

had kicked up a sensation when he first displayed it more than a dozen years earlier. Playing to a vogue for the romance of death, his bleak image drew avid crowds. Writer Grace Greenwood became enamored of it in the days before she took off to Rome with Edmonia’s future mentors. She gushed, “The face is wonderfully beautiful in the awful repose of death — a repose impossible to mistake for sleep…. How meet a place for a form of such majesty to lie in state!”

[54]

Edmonia could see it at the Athenæum, Boston’s first art museum and library.

Visualize the intense, bearded sculptor in his mid-40s bounded by a careful clutter of tools and dust at his studio. He must have looked quizzically at the tiny woman as he listened to Garrison’s request. It is likely he paged through some drawings she carried with her, taking in each with but a glance.

So, he might have barked at her, the war’s not even over and you want to be a sculptor? Well, all right, but I warn you: I am not a teacher. Let’s see what we can do.

He led her into a room filled with busts, some on pedestals, some on shelves, and more on the floor as casually as furniture. There’s

Wendell Phillips

and

Garrison

himself, he said. His

John Brown

radiated intensity, making viewers feel the presence of the man. He had made a daring visit to Brown’s cell where he found his hero about to face the hangman. He was in ox chains and deeply depressed. From his measurements, his memory, his skill, and his vision, he extracted a famous work of art. As a realistic portraitist, Brackett emphasized accuracy – but not at the expense of sentiment. The leading critic, Bostonian James Jackson Jarves, considered the bust “one of those rare surprises in art, irrespective of technical finish or perfection in modelling, which shows in what high degree the artist was impressed by the soul of his sitter.”

[55]

Thus, Edmonia met the champion that all Oberlin grieved and raged over, the martyr of the war against slavery and foremost among her life’s heroes. The sight of so many busts, lined up row on row, introduced her to portrait sculpture.

Brackett sent her back to her room with a lump of clay, some old modeling tools, and a cast of a baby’s foot. There, model that. If there’s anything in you, it will come out.

[56]

Brackett was self-taught. He had no more interest in giving lessons than he had in cutting blocks for a printer, his first job as a boy. He did not demonstrate and did not have her work under his watch. As she told it, he did not even agree to teach her. He simply gave her some clay and sent her home. Just keep it wet, he said.

It was a test. He would not talk to her until she showed him she was worth it. Enthused and impatient, she was back the next day with a rough but unmistakable foot. Pointing out failures in proportions and modeling, he said, Try again.

She struggled with the slippery stuff. At her small table, she moistened it and started over. It looked so simple. Yet, she could not copy it exactly. Push here and it changed there. When tired, she sat in stoic silence, looking at the clay and the cast. Small increments in her skills reassured her. Teaching her eye to see more sharply, educating her fingers to model more deftly, anticipating deformations under stress, she settled into an endless cycle that took the day’s vigor. Only when she was sure of her work, she took it back.

Envying the skills needed to accomplish his

John Brown

, she scrutinized the portrait more closely. How did he do that? Knowing Brown’s history, she could see in his image how he was visionary, resolute, ruthless, and fearless to the end. The effect was dramatic.